2017

Jérôme Sans │ A Journey through Immobility

2017

Hou Hanru │ Create A New Light

2017

후 한루 │ 새로운 빛을 밝히다

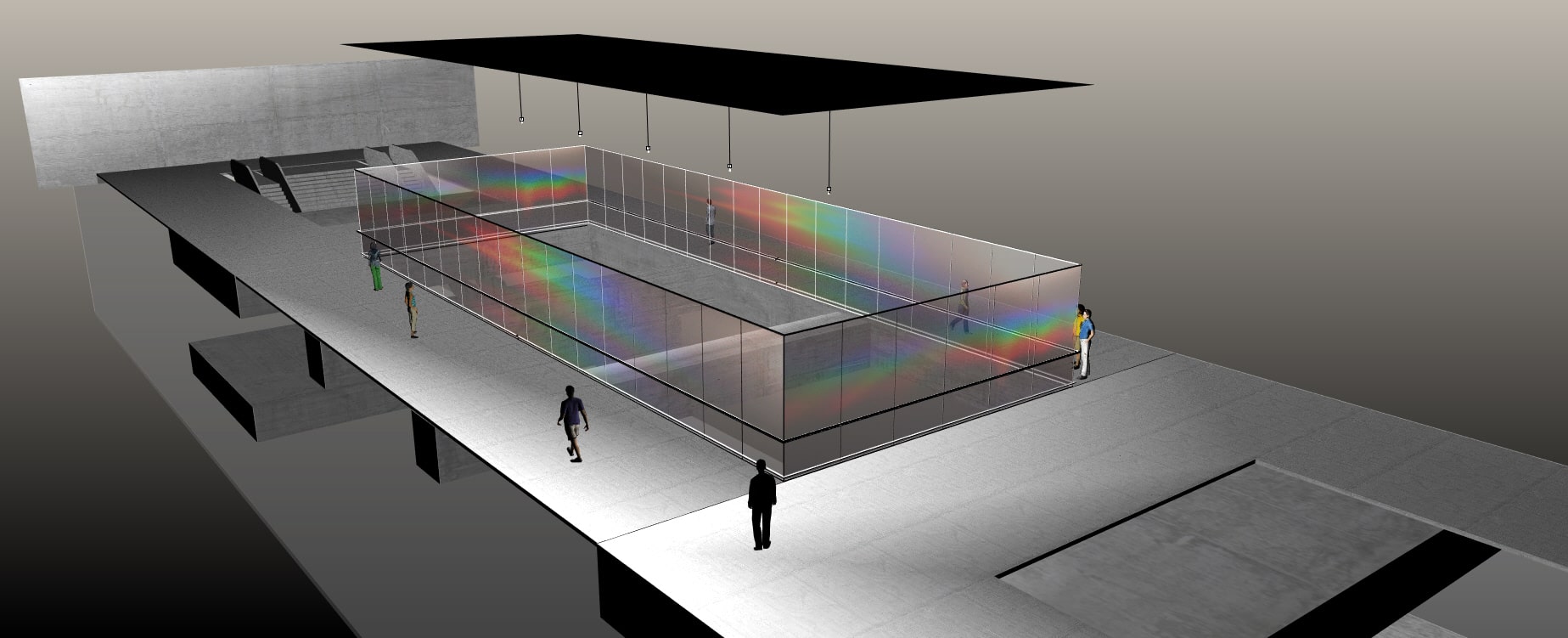

To Breathe, 2017-2021, Rendering of the Site Specific Permanent Installation, Mairie de Saint-Ouen Metro Staion, Paris, France. Commission of the RATP Régie autonome des transports parisiens. Courtesy of the RATP and Kimsooja Studio

To Breathe, 2017-2021, Rendering of the Site Specific Permanent Installation, Mairie de Saint-Ouen Metro Staion, Paris, France. Commission of the RATP Régie autonome des transports parisiens. Courtesy of the RATP and Kimsooja Studio

A Journey through Immobility

2017

-

Jérôme Sans

How would you define your work? -

Kimsooja

I view my work as a threshold: “any place or point of entering or beginning, a magnitude or intensity that must be exceeded for a certain reaction, phenomenon, result, or condition to occur or be manifested.” -

Jérôme Sans

Would you call some of your works self-portraits? Is it important that you yourself are in some works? -

Kimsooja

In some ways, my work could be viewed as a self-portrait. I do not wish to display my personal identity in my work—especially in the video performances when my back is facing the viewer—but the position demonstrated does show a certain kind of identity. I think a person’s back can be one of the most evocative parts of the human body; it isn’t dynamic, but it presents a profound and abstract encapsulation of a person. -

Jérôme Sans

How do you consider the globalized world? -

Kimsooja

A globalized world sounds very positive, dynamic, interconnected: a constant flow of cultural, economic, technological, and intellectual interactions. But we face many visible and invisible divisions created by constant border crossings: racial, economic, political, and religious conflicts. The standardization of daily life under globalism could benefit those who need it most, but we lose the authenticity, spirituality, and the myth of a land and its people. Globalism reduces the uniqueness and specificity of humanity, although new technology will bring a new facet. -

Jérôme Sans

What do you think of migration today? -

Kimsooja

More than five million Syrians have migrated to Greece, Turkey, Germany, and nearby countries; there is a constant flow from Africa to Southern Italy and Spain; people from Mexico and Central and Latin America try to get to the United States. As an artist who has always been concerned with borders, migration, and refugee issues, especially from living near the Korean Demilitarized Zone during my childhood, I am shocked by President Trump’s decision to block borders, deny immigrants a new life in the United States, and deport second-generation immigrants. American citizens have to pay attention to this humanitarian issue, especially since only a few organizations and individuals are focused on the refugee crisis. Major European countries are taking risks to support and help the refugees. Along with global warming, it is the most urgent issue of our time. -

Jérôme Sans

Your work deals with exile and displacement. Do you feel exiled too? -

Kimsooja

Definitely. I have considered myself a cultural exile since 1999. Recently, I’ve collaborated with Korean-specific projects, such as Année France-Corée for a solo show at the Centre Pompidou-Metz in 2015 and the MMCA Hyundai Motor 2016 project. Still, my position as an artist remains that of an outsider rather than insider, even though I’ve been well received. Perhaps it is the fundamental nature of being an artist? -

Jérôme Sans

You have lived in New York for several years, how have things changed for you? -

Kimsooja

Thanks to support from Arts Council Korea in 1992, I was able to participate in the P.S. 1 studio residency program in New York. I met people who understood my work and viewed it objectively, with enthusiasm and generosity. It really opened up possibilities for me. Due to the Korean financial crisis in the late 1990s, I was not able to receive financial and intellectual support for my work. It truly disappointed me and made me realize that I needed to find support outside Korea. -

In the last ten years, this has changed dramatically and Korea is now one of the most supportive countries in the world. However, when I go back to Korea, I am too established to get support from my country. The level of professionalism still needs to be raised, especially in governmental organizations. Where to live, work, and die are big questions. You need a nation to live—but you don’t need a nation to die.

-

Jérôme Sans

The idea of displacement is very present within your work. -

Kimsooja

All good art is made from thinking outside the box. In that sense, having displacement as a condition of life is not a bad choice for an artist. -

Jérôme Sans

In some of your works, like A Needle Woman (1999–2001, 2005, 2009), immobility rather than displacement is present. Is it a way to show personal identity toward the global world? -

Kimsooja

In my practice, the notion of duality and its complex geometry and disorder are always present through my understanding of the world. While I am presenting my immobility, which is impossible in literal terms, a lot of mobility happens in my body and mind, allowing me to reach to the place and moment of my performances. This immobility gives me an anchor to hold onto, so my journey flows through immobility. -

Jérôme Sans

Some of your works and installations are made with bottari, meaning, “to pack for a trip.” Which trip are you addressing? -

Kimsooja

The bottari represent our body and skin, their agony and memory as a wrapped frame for life. Bottari are the simplest way of holding objects or belongings that embody many meanings and temporal dimensions. A trip could be a simple A-to-B, or a relocation, or a separation of a couple in feminist terms, wrapping only the most essential belongings in an emergency—migration, exile, or our final journey: death. -

Jérôme Sans

Do you consider yourself as a nomad? -

Kimsooja

Yes, fundamentally. -

Jérôme Sans

Your work is an invitation to a sensorial and visual trip—a way to travel without moving. -

Kimsooja

We can easily grasp what is going on in this hyper-informed society, but we can’t experience true reality, not in depth. All experiences are limited by the conditions of space and time; I am determined to witness the here and now, living through my eyes and body, sharing my experiences with the audiences. -

Jérôme Sans

In the emblematic work, A Needle Woman, you stand in moving crowds. Who was this needle woman? And who is she now? -

Kimsooja

A Needle Woman is a woman who gazes at the world, gazing at and witnessing the world without acting. She allows us to take a journey to reality and reach for the ontological root—our destiny. She is there as a tool, a question, a permanency; I am here as a temporality. -

Jérôme Sans

In your installation To Breathe – A Mirror Woman (2006), shown in Madrid, we can hear your own breathing, filling the space. What is your relationship to the body and the act of breathing? -

Kimsooja

I’ve always reinterpreted and recontextualized existing concepts, depending on the site, the questions I had, and the relationship to other works and sites. This installation has three different components from past projects. The Weaving Factory (2004), was my first sound performance, I overlapped my breathing and humming; it developed from the idea of my body as a weaving machine, inspired by an old textile factory in Lodz, Poland, for the First Lodz Biennale. Later, I worked on a video installation commissioned by Teatro La Fenice, Venice, called To Breathe (2006), which incorporated The Weaving Factory. La Fenice is an opera house and singing is about breathing. When I was invited to make a work for the Palacio de Cristal in Madrid, I brought all of these elements together, contextualized as a bottari and as a void. Attaching the diffraction film to the architecture was an act of wrapping and unfolding the daylight into a rainbow spectrum. -

Jérôme Sans

One of your upcoming projects is a work for the new subway station at Mairie de Saint-Ouen in Paris. -

Kimsooja

Although it is a site-specific and permanent installation, this project brings me back to the body/work and audience/pedestrian relationships in A Needle Woman. This installation will symbolize another body of mine, one that witnesses the station’s pedestrians. The diffraction film installation will function as my body, standing still in the station and witnessing the pedestrians, while offering the public a forum. -

Jérôme Sans

You were teaching at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. What is your connection to Paris? -

Kimsooja

Paris was the first western city I visited; I stayed for six months in the mid-1980s. A scholarship from the French government allowed me to work at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in the lithography studio. Whenever I had a project in Europe in past thirty years, I’ve also visited Paris, even if I didn’t have any particular reason.

During my six-month stay in Paris, I traveled to other European cities for the first time, visiting major museums in Germany, Italy, Holland, and England. I was 27 years old. I absorbed the language, art, culture, and life in Paris, they are forever in my memory. In 1985 at the Biennale de Paris, I first encountered John Cage’s work. Although I knew of him as an avant-garde composer, I had never heard his music live, or seen any of his visual works. With great curiosity, I entered an empty railway car to hear his sound piece, but there was only silence and a simple written statement, “Que vous essayez de le faire ou pas, le son est entendu” (“Whether we try to make it or not, the sound is heard”).

It was interesting that I learned so much from an American avant-garde composer, rather than from European art or artists, although I was aware of the French Supports/Surfaces group and the influential artists at the time. After my encounter with Cage’s work, I became curious about American art and culture for the first time.

I’ve shown quite often in France, the French government and institutions have supported many of my works, and I owe them a lot. I was admitted to the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the Minister of Culture for my modest contribution to French culture. I have a love for Paris and French culture and want to spend more time working there. -

Jérôme Sans

What new avenues are you exploring? -

Kimsooja

Since 2010 I’ve been working on a 16mm film series titled Thread Routes, filming textile cultures from around the world: Peruvian weavings (chapter I), European lacemaking (chapter II), Nomadic Indian textiles (chapter III), Chinese embroidery (chapter IV), Native American weaving (chapter V), and African textiles (chapter VI). I can’t wait to visit Africa to film soon. Since 2016, I have realized a large-scale participatory installation titled Archive of Mind, firstly for a solo exhibition at the National Museum for Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, as part of the MMCA Hyundai Motor Series. This project is evolving and was presented at the Intuition exhibition at Palazzo Fortuny in Venice this year, and opens up to explore the sculptural aspect of my practice from the position of a painter. -

There is also a new installation at Nijo Castle, Kyoto, commissioned by the Culture City of East Asia, with the title Asian Corridor; it’s a ten-panel folding mirror screen on a mirrored floor, entitled Encounter – A Mirror Woman (2017). This is my second East Asian City project, the first, in Nara, was Deductive Object (2016), a black sculpture, inspired by an Indian ritual stone called Brahmanda (a cosmic egg in Hindu culture), installed on top of a mirror panel.

-

These works redefine the geometry of bottari and the surface of the symbolic bottari that represents the totality of the universe. I want to explore further what this could bring to my future practice. I am also starting new clay works. All of these are exciting, new directions to keep exploring, and I am very curious about the outcome.

-

Jérôme Sans

How do you see the future? -

Kimsooja

The future doesn’t exist anymore—it is past.

— Kimsooja: Interviews Exhibition Catalogue published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König in association with Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, 2018

- This interview was conducted in summer 2017 via email in conjunction with one of Kimsooja’s upcoming projects, a work for a new subway station in Paris.

Archive of Mind, 2016, participatory site specific installation consisting of clay balls, 19 m elliptical wooden table, and sound performance Unfolding Sphere, 2016. Installation view at Kimsooja - Archive of Mind at MMCA, Seoul. Courtesy of MMCA and Hyundai Motor Co. and Kimsooja Studio. Photo by Aaron Wax.

Archive of Mind, 2016, participatory site specific installation consisting of clay balls, 19 m elliptical wooden table, and sound performance Unfolding Sphere, 2016. Installation view at Kimsooja - Archive of Mind at MMCA, Seoul. Courtesy of MMCA and Hyundai Motor Co. and Kimsooja Studio. Photo by Aaron Wax.

Create A New Light

A Conversation between Kimsooja and Hou Hanru

2017

-

Hou Hanru

Let's start with travel. Today, we are constantly traveling: last week we were in New York and now you're in Berlin and I'm in Rome. Traveling has become a norm of contemporary life, both in the everyday and in the artistic... -

Kimsooja

Yes, traveling has become increasingly common in this era. In a way, we are living and working on the move. -

Hou Hanru

So this is really a state of being. Traveling is also a very important aspect in your work. From the beginning, you reflected on the question of identity from a female perspective, using traditional Korean textiles with your Bottari works. This question is also addressed from another perspective, that of an artist who is constantly traveling and moving. You look at the world through the lens of a nomad. Traveling has become a common motivation for people to reflect on the subject of identity. -

Kimsooja

Yes, definitely. -

Hou Hanru

On the other hand, travel has become a way of life, don't you think? -

K : Traveling has always been a part of my life. From a young age, I lived in various cities and villages, moving every couple of years within South Korea, including the Demilitarized Zone where my father served. Sorok Island, where my husband and I lived during his military service as a psychiatrist, was especially isolated from the public because it was used as a national hospital for leprosy patients. As a member of a nomadic family, traveling became my reality. My visual experience and perspective on nature and humanity have developed significantly from these transitory places and moments. One important experience was in 1978 when Hongik University, which I attended, started an exchange program with Osaka University; it was an eye opening experience about Korea and Korean cultural identity. Although Japan is only a short distance away, the trip altered my perception of Asian cultures and their differences. This began my investigation of my culture, such as the structural elements of architecture, furniture, language, nature, and sense of colors. I rediscovered that the aesthetics, the sensibilities of colors and forms, are very different in Korea and Japan. This period coincided with my investigation of the horizontal and vertical structures in nature, canvas, and all types of cruciform visual elements. This was the subject of my thesis, focusing on the cross in ancient and contemporary art. In 1984, I received a scholarship to the …cole nationale sup Èrieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris, to study printmaking for six months. It was my first exposure to European art and ancient culture; as a result, I started to inquire what is new in art and culture after European art history, and became interested in learning about American culture.

-

Hou Hanru

This led to a new direction in your life and work. Also, your traveling changed from national to international, from local to global. In the meantime, the image of bottari was introduced to represent this tension, between trying to be at home and travelling across the world. . . . -

Kimsooja

I didn't realize that my family had been wrapping and unwrapping bottaris all the time until I worked on Cities on the Move ─ 2,727 km Bottari Truck (1997), a performance and video project for the Cities on the Move exhibition, which you and Hans Ulrich Obrist curated in 1997. It marked a turning point in my work from local to global travel. I hadn't considered that I was dealing with global travel, as the journey was deeply personal. It was a record of my family's roots, but many people thought the project was dealing with globalism. Maybe that's true, in the sense that the performance can represent migration. Cities on the Move traveled to so many cities; the title served as its destiny and global exchange in the arts had been launched. -

Hou Hanru

Can you talk about your move to New York? -

Kimsooja

I consider my move to New York as a cultural exile from Korean society. It was the moment when I made more critical performances: the series A Needle Woman (1999-2001), A Homeless Woman (2000-2001), and A Beggar Woman (2000-2001). I made them right after I moved to New York during a transitional period I felt like I was stepping off a cliff, with one foot already in the air. This risky move made me reflect on my surroundings and the human condition more critically. I started living in Berlin recently, although I am not sure if it will be for the long term. It's interesting because it brings me back to when I established myself in New York in the late 1990s. That was a very difficult moment for me, every single step of the way, adjusting to a new society. Currently I am located in the Moabit area, which is a multicultural neighborhood. I like it, but I feel alienated. As an artist, I cherish this ambiguous state; distance and alienation bring me to a more objective and critical perception. I want to keep that critical distance all the time and New York provides that. Each time I arrive back in New York, I find a new definition, or have a specific feeling about New York, one that I haven't had before. When I feel that I'm losing perspective, I relocate myself, but I cannot deny that I somewhat respect the familiarity and rhythms of mundane life. -

Hou Hanru

You have spoken of being a Korean woman growing up in a family influenced by Confucianism. Obviously, you were aware of very important social and political changes in Korea in the 1980s and 1990s. Maybe growing up in a military family allowed you to experience this change in a way that other people would not? How much has this background influenced your way of thinking and art making? Was there was a moment of emancipation from this background? -

Kimsooja

Both of my parents were from Catholic families and very open-minded; however, as my father was the only son, he had to follow the traditional Confucian ways, which were deeply rooted in Korean society. -

As a military family, we lived in temporary and sometimes dangerous places, like refugees, migrating from one place to another. During my elementary school years, I lived near the Demilitarized Zone, in and around Cheorwon and Daegwang-ri, the second to last stop on the Kyung-Eui train line, which used to run all the way to North Korea. We often heard stories about North Korean spies who snuck into South Korea, and there were casualties every now and then. We didn't live far from a mined area; kids played with the spent bullets and would get injured by the landmines. I am of the generation, born a few years after the Korean War, who really experienced the conditions of the war and the conflict that it brought to our daily lives. Iive always been aware of the Other, because of my daily experience with the border. My thoughts on borders and those living on the other side made me question the relationship between myself and the Other. The idea of a border and questioning it had to do with being a painter reacting to the canvas as another border. I tried to overcome this border, or limit, in front of me, and connect with the Other. This was also part of the psychology in my sewing practice. The act of wrapping, with bottaris, is a way of three-dimensional sewing; it is unifying in that sense. Borders have always been part of an underlying psychology and challenge in my work.

-

Hou Hanru

In the 1980s Korea transitioned from a military dictatorship to a democracy. You began exhibiting your work during this period, can you describe your early exhibition experiences? -

Kimsooja

I started showing in 1978 when I was in my third year at Hongik University; it was a two-person show at the Growrich Gallery in Seoul. I hung a series of transparent films on a laundry line; they were silkscreened with images of a traditional Korean doorframe taken in a forest, one showed me holding it from behind and one was without me. I also installed two pieces of wood, inserting Plexiglas between them, with the wood blocks slightly tilted and following the curves of the wood. The other artist was my classmate Lee Yoon-Dong, who experimented by dripping black coal tar pigment on canvas; the work questioned gravity and materiality and its rhythm. I showed a few times in Japan and Taiwan in the mid- to late-1980s and in the US after the early 1990s, but it was not until the mid-1990s that I started to exhibit more globally. Some shows included Division of Labor: Women'ss Work in Contemporary Art at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, which traveled to the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles (1995), the First Gwangju Biennale (1995), and Manifesta 1 at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam (1996). -

Hou Hanru

Globalism has expanded and affected much of our thinking about our way of making art, and our way of living. It seems almost inevitable to work globally, especially as I work a lot with site-specific performances, installations, and videos. Many female artists were extremely active and audacious in their work often performances during this transitional period in the 1990s. Lee Bul is another well-known female artist. How did you feel about this? And why did you decide to leave Korea in 1999, right after participating in the Twenty-fourth S„o Paulo Biennial (1998)? -

Kimsooja

In the 1990s, female artists, including myself, were engaged in performances using their bodies. I think that had to do with womenís social status in Korea at that time. Many female artists were associated with feminism. But performance art was already popular in the 1970s and 1980s in Korea, under the rubric of Happenings or Events, mostly by the Avant-Garde group, or the S. T group, which was entirely male, except one female artist, Chung Kang-Ja. During the mid-1990s, women did not have the equality they have now much of our daily lives was governed by a patriarchal Confucian value system.

After my residency at P.S. 1, Long Island City, NY (1992ñ93), my first solo show was at Seomi Gallery in Seoul; I showed three of my first performance videos Sewing into Walking ─ Kyungju, Yang Dong Village, and Mai Mountain (1994), and a Bottari installation. Used clothes were also installed on the gallery floor together with rows of TV monitors with Bottaris as a ìmedia Bottari,î and surveillance camera footage of re-wrapping the space of the wrapped Bottaris. These works could have been easily associated with feminism, but I refused the feminist label, owing to the formal and conceptual elements of my Bottaris, and my approach to universality. As a female artist, it was not easy to survive in this hierarchical and patriarchal society, or even in the global art world, until now. I noticed Korean social and cultural issues more clearly after my return from the P.S 1 residency. At the same time, economic development changed Korean society, which was quickly shaken by the financial crisis starting in 1997. I was chosen to represent Korea for the Twenty-fourth S„o Paulo Biennial, but I couldn't get any state support, only from a couple of individuals and a commission from ARCO. Korea wasn't able to ship my Cities on the Move ─ 11,633 Miles Bottari Truck (1998) from Korea to S„o Paulo. I felt hopeless and disappointed by my country, and I had to accept personal support from Korean-Brazilian immigrants who had heard about my situation. This situation confirmed my decision to find support elsewhere, so I moved to New York. -

I established myself as an artist without much support from my home country until recently. After the late 1990s financial crisis, the slowly growing Korean art market and Korean journalism often misled audiences by promoting marketable and status-oriented artists. My career trajectory is totally different from that of older and younger generations, who constantly receive support from the state and their galleries.

-

Hou Hanru

Around that period, several important art movements were created by students to oppose the power of the establishment. -

Kimsooja

Minjung Art was one and there were many modernist and postmodernist group activities that were against the established movements, such as Nanjido and Metavox from the mid-1980s. The newer groups were organized by artists from Hongik University, where I studied. Other groups Museum, TARA, Logos and Path were also around. I kept myself completely independent, although I was friends with some of the members. -

Hou Hanru

Minjung Art and artists from your generation represented a tendency toward conceptual and experimental forms of creation, especially performance and installation. What was your role? -

Kimsooja

Prior to my generation, there were experimental modernist group movements, such as the Avant-Garde and S. T. groups, which coexisted with the Dansaekhwa artists. I didnít follow Dansaekhwa art theory or practice, although the theories were predominant at Hongik University. Also, there was a big age gap between my generation and the Dansaekhwa members.

When I was at Hongik University attending undergraduate and graduate school (1976-1980 and 1982-84), the Minjung Art movement was slowly happening and I knew a few of the leading members. We would meet casually in a study group, as I was intellectually interested for some time, but when they wanted me to join, I couldn't because I always had a certain resentment about focusing only on political issues and such dogmatism. I couldn't connect with the aggression of some of the political art. At that time I was making art that was abstract, performative, conceptual, and spiritual. -

I had zero interest in any group or collective activities. I always kept myself independent by questioning the monopoly of the Dansaekhwa group, to which most of my professors belonged. I voiced my opinions in classes to open up the dialogue, offering my fellow students different possibilities and perspectives. I kept myself completely isolated, to be independent from political and artistic hierarchies, to preserve my own integrity. It has been a long and lonely path. To address further your question about my role in performance and installation in a Korean art context: the large scale of my site-specific installations and global performance projects in the 1990s and early 2000s might have influenced a younger generation in Korea, as I see many are expanding their practices. live noticed that some of my interests the notion of the needle, thread, wrapping, and unfolding have achieved wider currency in current contemporary art, particularly in art concerned with the body, textiles, and everyday life.

-

Hou Hanru

People often identify you as a leading figure, together with a few younger artists such as Lee Bul or Choi Jeong-Hwa. They express similar positions, confronting the status quo, social and political situations. Lee Bul's work is a kind of counter-violence against oppression, while your work is much more related to meditation and transcendence. You use intimate materials such as textiles and bottaris. How did you arrive at this language? -

Kimsooja

I cannot associate with any type of violence or raw expression. In that sense, Iive been working closely with non-violence and that is my position to the individual and society. I couldn't and didn't engage directly with political issues. The artistic language that I created has always stemmed from a healing perspective, maybe because of my compassion for humanity and my vulnerability to violence. -

This vulnerability might be rooted in my childhood experience of living near the Korean border, among others. I felt innately vulnerable. I cannot watch scenes of violence and my inclination has always been to embrace and connect with those around me. However, it is true that I gain strength through resistance and patience. Maybe this mindset originated when I discovered sewing and needlework as a methodology for healing despite the violent potential of a needle. Searching for my own medium, I focused on vertical, horizontal, and cruciform structures in the world. In 1983, when I was making a bedcover with my mother, I was about to push the needle into the brilliant, soft, and silky fabric but when the needle touched the fabric, I experienced a revelation, as if the whole universe's energy passed through my body to the tip of the needle. I immediately recognized the relation with this border, the surface, and the vertical and horizontal woven structure that was penetrated by the needle. The fabric had a woven vertical and horizontal pattern (warp and weft) and I saw this as a way to investigate the surface of a structure as a painting. This action and experience was the moment that I interwove myself as a person who is innately vulnerable, seeking to connect with and embrace those around me.

-

At the same time this experience coincided with my artistic struggle to redefine the structure of the surface of a canvas. I'd been trying to find an original painting methodology for a number of years, since beginning college. That was the moment I discovered sewing as a methodology for painting, using the fabric of life as a canvas and the needle as a brush. The concept of needle and sewing evolved naturally into social, cultural, and political dimensions and has expanded with a broader context into my current practice.

-

Hou Hanru

For many years, you have developed this process of wrapping and unwrapping bedcovers, carrying them on your travels, and showing them as installations. They are more than luggage, more like real companions. They have become your partner as you travel. It's like having a life that you can carry around with you in your global displacements. During the last few years you extended this interest, engaging with textiles from other cultures and places. For example, you went to Peru to work with the local women and filmed the weaving culture, called Thread Routes ─ Chapter I (2010). -

Kimsooja

Yes, Thread Routes continued with Chapter II (2011) filming lace making in European countries, block printing, embroideries and weavings in India (Chapter III, 2012), embroideries in China (Chapter IV, 2014), and basket weavings in Native American communities (Chapter V, 2016). I am also planning to film weaving in African cultures (Chapter VI). -

Hou Hanru

That gives your vision broader cultural dimensions. -

Kimsooja

I consider the Thread Routes films as a retrospective of my formal practices related to thread and needle, with the textile as a canvas and a structural investigation. It was conceived in 2002 in Bruges, when I first saw a bobbin lace maker on a street. It immediately inspired me to juxtapose it with the local architectural structures, as a sort of masculine lacemaking, but it took a long time to start the actual film. I finally started, using 16 mm film, with textiles in Peruvian culture. It's a non-narrative documentary film, using only visual juxtapositions with minimal environmental sound. I wanted to approach this project as anthropological poetry, capturing the long, silent journey of textile cultures around the world, revealing similarities and differences, different production methods. Through the camera's lens, I wanted to reveal each culture's craftsmanship as a living form in textile, in architecture, and in nature. -

I didn't use Korean secondhand bedcovers because I was interested in orientalism or local aesthetics, but because they were part of my daily life in Korean society. It's the same reason that Europeans or Americans use their local materials, so there is nothing exotic about them, although Westerners might view them that way. The material I chose for the Bottari works was not originally wrapping cloth. Initially, I chose a bedcover for wrapping as the bed is the place for our bodies to rest, as a frame of life where we are born, love, dream, suffer, and die. This symbolic site carries all of our dreams, love, agony, pain, and despair throughout our lives. The colors are striking and have extreme contrasts, but I didn't choose the colors for aesthetic reasons, they just came with the fabric as cultural symbols, symbols of the daily life that I lived. I accepted what was created and what was handed down from our parents upon marriage. The wrapping and unwrapping is another language I discovered when looking at an existing bottari bundle in 1993. Bottaris are common universal objects, existing in all cultures, but the bottaris I discovered at my P.S. 1 studio appeared to me in a completely different context: a totally different object that was a painting in the form of a wrapped canvas, a ready-used object, a sculpture, and a performed object that unifies the form as a totality.

-

Hou Hanru

One of your recent projects, An Album: Sewing into Borderlines (2013), is on the American-Mexican border, initiated a few years ago under the federal General Services Administration Art in Architecture Program. In the beginning, you wanted to work with people who had been deported from the US, but since the GSA could not accommodate that project, you shifted to working with migrants who cross the US-Mexican border every day to work. -

Kimsooja

In the end, I focused more on the positive, welcoming aspects of migration for the different generations of Mexican immigrants traveling to the US. It was during the Obama administration, when artists were supported during the economic crisis more about hospitality than despair. -

Hou Hanru

But now the policy of the new government forces you to raise new questions about the issue. The political structure under Trump is a different situation. How will this change influence your project? You have been interested in female migrants, who have a very different life and experience with migration than men do. -

Kimsooja

Women are central to the migration chain; they are the major nexus, connecting everyone in the family. Women travel on more visible routes like trains, cars, and buses, which makes them more vulnerable to arrest. Generally one-third of women are deported. Men use riskier methods, on foot through the desert or by boat. There are even tunnels dug under the border. Female migration is more transitional. Women work for others, generally in homes or little stores during their migrations. They stay in one place for a short time, earn some money, and then move on. -

Hou Hanru

You developed this project along the US-Mexican border, where migrants are both caught and detained. -

Kimsooja

The GSA project, which is a permanent installation at the land port of entry in Mariposa, Arizona, was installed right on the border. I installed large LED screens with portraits of the immigrants who cross the border, commuting to work every day. I filmed each portrait from the front and back, showing each person's psychological journey in a durational gaze. I would call their names and they would turn to the camera, creating a psychological border between themselves and the Other first the camera and then the public. I focused on the juxtaposition of their psychological borders with the political border where the work is installed. -

I learned a lot about the border situation between Mexico and the US. Lately, the social, political, and cultural geography has shifted because of Trump's immigration policies, especially with Mexico. This new view on immigration is the most urgent and critical issue to address right now.

-

I began to research the new reality Mexican immigrants are facing since last year. There are interesting organizations that support women's migration, including El Instituto para la Mujeres en la Migracion (Institute for Women in Migration). Interestingly, the organization is supported mainly by American non-profit organizations. I researched the conditions of women migrating in South America, especially in Mexico. There's a constant migration through Mexico. The organizations support detained family members, women, or children, by providing shelter, educational programs, and further support. Families get separated, sometimes women are detained and sent back to Mexico, but if their kids were born in the US, then the children enter the care of these organizations. The children are then moved to a shelter where their mothers cannot see them. Once in the shelters, American families can adopt the children and change their names. Basically the mothers no longer have any rights to their children after they are adopted. So, there are efforts to reunite these families. It is not only a migration issue; it's also a whole family-related issue.

-

The importance of the women's role in a family experiencing migration made me think of dealing with women as central figures. For this new Mexican immigration project, yet untitled, I want to have female performers wearing national flags. The location will be a former route from where the Spanish conquered Mexico. I'll film the performance between two volcanoes in the Valley of Mexico, one of which, IztaccÌhuatl, is also know as the Mujer Dormida or the Sleeping Woman. There is a myth surrounding these two volcanoes (the other one is PopocatÈpetl): they symbolize grief and the eternal love between a man and a woman.

-

Hou Hanru

Obviously, this covers issues far beyond the specific question of immigrant families. It should be extended to explore the question of all relationships, the human family. For your new exhibition in Seoul, Kimsooja: Archive of Mind, National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art (MMCA), Seoul, you installed a huge oval table covered with clay balls that are made by the audience. Can you explain this project and its participatory aspect? -

Kimsooja

I've been interested in clay and ceramics for a long time. My interest is more in the void that the vessels create, rather than the vessel itself. I was invited to participate in Water Event for Yoko Ono's solo show, LumiËre de líAube, at the MusÈe díart contemporain, Lyon, 2016; the Biennale de Lyon invited artists to create water containers. At the time, I was thinking about the clay ball as a Bottari, but also as the Earth, as a container. So rather than creating a void to contain water, I decided to make a clay ball as a pre-existing water container and address environmental issues. I sent a small clay ball that was still drying. Since then, I have been contemplating the formation of clay balls, how its creation has a psychological and meditative effect on the maker. When you make a clay ball you have to push your fingers and palms toward the center. A sphere is made by pushing from every point on the surface. It's not easy to make a perfect sphere because you need to smooth every angle. The action of pushing opposing sides toward the center is similar to producing gravity within the sphere. To make the smoothest sphere, you roll the clay ball between your palms. It's like a wrapping action, similar to making Bottari. This repetitive rolling action creates a spherical shape in your mind. I was working with my assistants with this clay and we reacted to it instinctively, enthusiastically touching it, rolling it. I found this instant reaction and concentration very interesting. It made me think that this project is not only for me to experience, but might even be more important for the viewers as participants. I decided to make an enormous communal table, bringing everyone together, sharing this experience at this elliptical wooden table, 62 feet (19 m) long. Each person has his or her space and time, but the work also creates a communal space, a communal society, working together toward a certain state of mind, creating a kind of cosmic landscape, a mind-galaxy. -

Hou Hanru

Like a field? -

Kimsooja

Yes. I made the large table out of 68 smaller tables, which are made from irregular shapes to construct the elliptical geometric shapes. I also installed a sound piece, Unfolding Spheres (2016), with thirty-two speakers under the table, and a 16-channel soundtrack. One part is the sounds of the dried clay balls rolling, crushing, and touching, recorded with 4 or 5 different microphones. Because sound is only made when the ball touches an angled corner, it reveals the geometry of the clay ball. At the same time, it creates a cosmic sound: when the balls bang loudly, it produces a sound like a thunderstorm. I also made an audio performance, gargling with water in my throat, like a grrr sound. Sometimes it sounds like a stream, then it reveals more of the verticality of the rolling spheres, pushing air against gravity. It has a vertical force or movement, while the sound of the clay balls rolling reveals a horizontal axis. Iive engaged in this vertical-horizontal structural relationship since the late 1970s. I also showed Structure ─ A Study on Body (1981); for this series of prints, I moved my arms at 90? to create geometric shapes, such as a triangle, circle, octagon, or square, to connect my body to the earth and the sky. I also included different colors to create different geometric shapes between my body and to determine the space around it. These prints directly connect to my sewn works, which have vertical-horizontal structures. -

Hou Hanru

You mentioned a cosmic sensation, the connection between the body and the world. I think one interesting aspect of this work is the relation between the body and architecture, highlighted through your use of light. For example, with your installations, Respirar ñ Una Mujer Espejo / To Breathe ñ A Mirror Woman, at the Palacio de Cristal, Madrid (2006), To Breathe: Bottari for the Korean Pavilion at the Venice Biennale (2013), and now To Breathe (2016) in the exhibition at the MMCA, you have created beautiful environments with diffraction grating film applied to the windows. The light enters and creates a rainbow spectrum; it transforms the interior, giving it a cosmic feeling. On the other hand, in the Korean Pavilion there was an additional room, which was completely dark and silent. This is a fascinating contrast between the two aspects of cosmic existence. It seems to be a new dimension of your work developed in the last few years. -

Kimsooja

In the MMCA courtyard I used the same film as in the Palacio Cristal and the Korean Pavilion. In a way, the painting or pigment was transmitted into light. This particular film has thousands of vertical and horizontal lines in every inch. It has a woven structure and functions like a prism, creating iridescent light when light passes through it. This is one of my investigations into the structure of painting, of canvas, and of color and pigment in relation to light. I created a completely dark and silent space, an anechoic room, to define the nature of light and sound. It was the opposite state of visualization, operating in connection with my questions of duality in both life and art. My questioning of duality the vertical and horizontal structure of the canvas relates to the psychological structures, the mandalas in our mind. -

My Master's thesis was on the symbol of cross, from antiquity up to contemporary painting and sculpture. This cross and the horizontal-vertical structure are always present in art. Iím curious how it constantly reappears despite contemporary art's desire for creativity and innovation. Many artists reach this point, confronting this very basic structure: Piet Mondrian, Kazimir Malevich, Joseph Beuys, Antoni T‡pies, Lucio Fontana, Frank Stella, and many more. Iive always questioned the inner structures of our world and our psychology. In my thesis I identified a relationship with psychological geometry of the Mandala, which utilizes cross structures and Carl Jung's archetypal phenomena theory. This isn't unrelated to my question of duality in art and life.

-

When I was planning the Korean Pavilion, I experienced Hurricane Sandy in New York. I was living in complete darkness without any electricity for more than a week. I questioned the fear I had while walking in the dark in my building and on the streets, especially when someone is walking toward you. I realized that the fear occurs in our mind because of the unknown ignorance of the Other. The unknown and the ignorance in the human mind were the questions I had at that time. Eventually, the relationship between light and darkness, sound and silence forming an architecture of bottari was what I created in the Korean Pavilion.

-

Hou Hanru

This can be a perfect conclusion. Now we all live in a kind of darkness, and we need to find a way out, to create new light. -

Kimsooja

Precisely.

— Essay from Exhibition Catalogue 'Kimsooja: Archive of Mind' published by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, 2017. pp.18-85.

Archive of Mind, 2016, participatory site specific installation consisting of clay balls, 19 m elliptical wooden table, and sound performance Unfolding Sphere, 2016. Installation view at Kimsooja - Archive of Mind at MMCA, Seoul. Courtesy of MMCA and Hyundai Motor Co. and Kimsooja Studio. Photo by Aaron Wax.

Archive of Mind, 2016, participatory site specific installation consisting of clay balls, 19 m elliptical wooden table, and sound performance Unfolding Sphere, 2016. Installation view at Kimsooja - Archive of Mind at MMCA, Seoul. Courtesy of MMCA and Hyundai Motor Co. and Kimsooja Studio. Photo by Aaron Wax.

새로운 빛을 밝히다

김수자, 후 한루 대담

2017

-

Hou Hanru

여행에 관한 이야기로 우선 시작해보자. 요즈음 우리는 끊임없이 여행을 한다. 지난주 우리는 뉴욕에서 만났는데, 이제 당신은 베를린에 있고 나는 로마에 있다. 일상에서든 미술에 관한 것이든, 여행은 오늘날 우리 삶에서 필수적인 활동이 되었다. -

Kimsooja

그렇다, 여행은 점점 삶의 방식으로 자리 잡고 있고, 우리는 이동하며 살고, 또 이동하며 일하고 있다. -

Hou Hanru

이렇게 여행하는 삶은 우리 존재의 일부가 되었고, 또 여행은 당신의 작업에서도 매우 중요한 부분이다. 초기부터 한국 전통 이불보를 사용한 보따리를 만들며, 여성의 관점에서 정체성 문제를 제기해왔다. 또한, 끊임없이 여행하고 이동하는 노마드와 이주자의 관점을 통해 세상을 바라본다고 할 수 있겠다. 현대인에게 여행은 자신의 정체성을 되묻는 하나의 도구가 되기도 한다. -

Kimsooja

그렇게 된 셈이다. 사실 여행은 늘 내 삶의 일부였다고 할 수 있다. 한국에서만 하더라도 어렸을 때부터 거의 몇 년마다 이 도시에서 저 마을로 이사를 하곤 했는데, 어린 시절, 직업군인인 아버지가 근무하셨던 비무장지대 부근에서 몇 년을 살았다. 또, 결혼 후 남편이 군의관으로 근무할 때는 소록도에서 2년간 살기도 했다. 그곳은 한센병 환자들을 돌보는 국립 의료 기관이 있던 특수한 곳이어서 일반인이 살 수 없었다. 방랑하며 떠도는 가족의 일원으로서, 어린 시절부터 여행은 자연스럽게 나의 일상이 되었다. 이처럼 일시적으로 거쳐 가는 장소와 시간으로부터 큰 영향을 받으며, 자연과 인간성(humanity)에 대한 나의 시각적 경험과 관점이 형성되었다. 그런 의미에서 1978년 홍익대학교 재학 시절, 일본 오사카 대학교에 방문했던 것은 내게 중요한 여행이었다. 이 여행을 통해 나는 아시아의 여러 문화와 그 차이에 대해 새롭게 인식하기 시작했고, 이때 한국의 문화적 정체성에 관해 보다 명확하게 눈을 떴다고 할 수 있다. 당시의 일본 여행을 계기로 내가 성장해온 문화, 즉 건축, 가구, 언어, 자연, 색감 등 구조적 요소들을 새로운 시각으로 바라볼 수 있었다. 일본은 거리상 매우 가깝지만, 미학, 색과 형상에 대한 한국과 일본의 감성이 매우 다르다는 것을 발견했다. 당시 자연, 캔버스, 온갖 십자형의 시각적 요소에 자리한 수직과 수평의 구조에 대해 연구했고, 이를 토대로 대학원에서 고미술에서부터 동시대 미술에 나타난 십자가 형상에 대한 졸업 논문을 썼다. 1984년 나는 프랑스 정부 장학금을 받아 6개월간 파리에 머무르게 되었다. 이 시기에 유럽의 고전 문화와 미술을 직접 접하게 되었는데, 이때 나는 ‘유럽 미술사 이후에 어떤 새로운 미술과 문화가 있고, 또 어디에 있는 것일까?’라고 자문하기 시작하며 무관심했던 미국 문화에 비로소 흥미를 느끼기 시작했다. -

Hou Hanru

이 경험을 통해 당신의 삶과 작업 모두가 새로운 방향을 갖기 시작한 것이라고 할 수 있겠다. 또한, 당신이 여행하면서 겪은 일들은 지역적인 것에서 세계적인 것으로 변화했다. 그러면서 보따리의 이미지는 집이라는 보금자리에 머무르려는 것과 전 세계를 여행하는 것 사이의 긴장 관계를 드러내기 시작했다. -

Kimsooja

당신과 한스 울리히 오브리스트(Hans Ulrich Obrist)가 공동 기획했던 《떠도는 도시들 Cities on the Move》(1997)에 선보였던 퍼포먼스 및 비디오 프로젝트 <떠도는 도시들-2,727km 보따리 트럭 Cities on the Move-2,727km Bottari Truck>(1997) 전까지 우리 가족은 매번 보따리를 싸고 풀었는데도 그 사실을 전혀 인지하지 못했다. 이 프로젝트는 나

의 여행이 지역 단위에서 국제적인 범주로 확장하는 계기가 됐다. 이 작업을하며 떠돌았던 여행은 매우 개인적이었기 때문에, 나는 내가 글로벌리즘과 연관되어 작업을 하고 있다고 생각해본 적이 없었다. 오히려 이 프로젝트는 나와 우리 가족의 뿌리에 관한 기록에 가까웠는데, 아이러니하게도 많은 사람들은 내가 글로벌리즘에 관해 논하고 있다고 여겼다. 그 퍼포먼스가 이주에 관한 문제를 드러내고 있다는 점에서는 그러한 견해가 틀린 것은 아니라고 할 수 있다. 결국 《떠도는 도시들》은 전 세계 여러 도시를 순회하게 되었는데, 제목처럼 전시도 그 방랑의 운명을 따랐고, 미술계의 국제 교류도 보다 더 활발히 진행되기 시작했다 -

Hou Hanru

뉴욕으로 이사했을 때에 관해 더 이야기해 줄 수 있을까? -

Kimsooja

내가 뉴욕으로 떠났던 것은 일종의 ‘문화적 망명’이었다.

돌이켜 보면, 이 시기는 내게 매우 중요했고, 나의 중요한 퍼포먼스 작업인 <바늘 여인 A Needle Woman>(1999∼2001)과 <집 없는 여인 A Homeless Woman>(2000∼2001), <구걸하는 여인 A Beggar Woman>(2000∼2001)

시리즈도 뉴욕으로 이주했던 바로 직후 제작되었다. 마치 벼랑 끝에서 한 발을 공중에 내디딘 채, 나머지 한 발을 허공에 내딛고 서 있는 것 같았다고 할까? 한국을 떠나기로 결정한 것은 큰 모험이었고, 그로 인해 나의 주변 상황과 인간적 조건에 대해서도 더욱 철저하게 고민하게 되었다. 2008년 이후 수년간 파리를 오가며 일하다가 올해 들어 베를린에서 조금씩 머물기 시작했는데, 아직 확실하지 않지만 뉴욕과 베를린을 오가며 일하는 것을 고려하고 있다. 1990년대 후반 뉴욕에서의 삶이 시작되어 고심하던 때로 돌아가는 것 같아 내 삶의 우여곡절이 흥미롭기도 하다. 당시 새로운 사회에 나를 적응시키던 걸음 걸음이 무척이나 힘겨웠었다. 현재 베를린에서는 여러 문화적 배경을 가진 사람들이 모여 사는 모아비트 지역에 머물고 있다. 이곳이 흥미롭기도 하지만 꽤나 낯선 느낌이 드는 것도 사실이다. 작가로서 불확정적인 이 상황을 소중히 여기기도 한다. 거리감과 낯섦은 언제나 내가 더욱 객관적이고 비평적인 관점을 견지하도록 이끌어준다. 이러한 비평적 거리감을 늘 유지하고 싶은데, 그러한 면에서는 뉴욕이 내게 적합한 도시이다. 여행을 마치고 뉴욕으로 돌아올 때마다 이전에는 생각하지 못했던 방식으로 이 도시를 새롭게 정의하게 되고, 또 전에 느끼지 못했던 특별한 감정을 느끼곤 힌다. 어떤 비판적인 관점을 잃어가는 것 같다고 느끼면 나는 나 자신을 또 다른 생경한 곳으로 밀어 넣곤 하지만, 결국 나 역시 평이한 삶의 리듬과 친숙함을 어느 정도 원한다는 것을 부정할 수는 없다. -

Hou Hanru

당신은 나에게 유교적 가치관에 영향을 받은 가정에서 한 한국 여성으로 살아가는 것에 관해 말해준 적이 있다. 1980∼1990년대에 한국이 매우 중요한 사회적, 정치적 변화에 놓여 있었다는 것을 당시 분명히 알고 있었을 것 같다. 군인 가정에서 자랐기 때문에 이 변화를 다른 사람들은 인지하지 못했을 방식으로 느끼진 않았을까 한다. 이러한 배경이 당신의 사고방식과 작업 방식에 얼마나 영향을 끼쳤을까? 그러한 조건과 환경에서 해방되는 순간도 있었을까? -

Kimsooja

부모님 모두 몇 대째 가톨릭 신앙을 이어 온 집안에서 자랐다. 부모님은 매우 개방적인 분들이었으나 우리는 종손으로서 유교적인 한국 가정의 시스템에서 크게 벗어나지 못하고 있었다. 동시에 마치 피난민처럼 이곳저곳 정처 없이 이주하며 살았다. 때로는 위험한 지역을 오가며. 초등학교 시절에는 비무장지대 근처, 철원과 대광리 안팎을 오가며 살았는데, 이 지역은 과거 북한으로 이어졌던 경의선 종착지 바로 직전의 정거장이 있었던 곳이다. 월남한 간첩에 관한 이야기를 자주 듣기도 했고, 사고가 오늘내일 끊이지 않았다. 우리 가족이 살던 곳은 지뢰밭에서 그리 멀지 않은 곳이었다. 동네 아이들은 탄피를 주워서 놀기도 했고, 지뢰 때문에 크게 다치거나 동상에 걸려 손가락을 잘라야 하는 경우도 있었다. 나는 한국 전쟁이 발발하고 몇 년 후에 태어난 세대에 속하기 때문에, 우리 일상에 난입했던 전쟁과 갈등의 양상을 직간접적으로 겪었다고 할 수 있다. 더구나 국경 주변에서 일상적으로 겪었던 일들 때문에 나는 늘 ‘타자’를 인식하며 살아왔다. 경계와 그 경계 너머에 살아가는 이들을 생각하면서 나 자신과 타인의 관계에 대해 자문하게 되었던 것 같다. 경계(border)라는 개념, 그리고 이것에 대해 질문을 던지는 것은 내가 화가로 살아가는 태도와도 관련이 있다. 또 다른 경계인 캔버스에 반응하는 것처럼. 나는 내 앞에 놓인 경계 혹은 한계를 극복하고, 그 너머의 타자와 소통하려 노력해왔다. 바느질 작업의 심리 작용 역시 이와 같다고 할까. 보따리로 무언가를 싸는 행위는 삼차원적 바느질과도 같다. 그런 의미에서 감싸기는 통합하는 것이고. 경계는 언제나 내 작업의 기저를 이루고 있는 심리적 상태이자 과제인 셈이다. -

Hou Hanru

1980년대 한국은 군사독재에서 민주주의 사회로 변화했다. 당신 역시 이 시기 대중 앞에 작품을 전시하기 시작했는데, 초창기 전시 경험에 대해 이야기해 줄 수 있겠나. -

Kimsooja

처음 전시에 참여한 것은 1978년 대학교 3학년 때였다. 지금은 사라진 서울 그로리치 화랑에서 열렸던, 대학 동기 이윤동과의 2인전이었다. 나는 나무로 된 한국의 전통적인 격자형 문창살을 들고 숲속에 선 나의 퍼포먼스를 촬영한 사진과, 내가 제거된 상황을 투명한 필름에 실크스크린으로 인쇄하여 빨랫줄에 걸어 전시했다. 바닥에는 몇 토막으로 자른 가는 통나무를 선이 흐르는 방향을 따라 어긋나게 설치하고, 그 갈라진 틈에 투명한 사각 플라스틱을 끼워 넣어 투명성과 수직·수평성을 드러내고자 했다. 함께 전시했던 이윤동은 캔버스 천에 검은색 콜타르 염료를 드리핑(dripping) 기법으로 실험한 작업을 출품했는데, 이 작품은 중력, 물질성, 리듬에 관해 질문하고 있었다. 이후 나는 1980년대 중후반 일본과 대만에서 몇 차례 전시했고, 1990년대 초반부터는 워싱턴과 뉴욕 MoMA PS1, 뉴 뮤지움에서 작업을 선보였는데, 1990년대 중반부터 비엔날레를 무대로 본격적인 국제활동을 시작했다. 1995년 뉴욕의 브롱크스 미술관에서 LA 현대미술관으로 순회했던 《노동의 영역: 현대미술에서의 여성의 작업 Division of Labor: Women

’s Work in Contemporary Art》, 1995년 제1회 광주 비엔날레, 1996년 로테르담의 보이만스 반 뵈닝겐 미술관에서 열린 제1회 마니페스타, 1997년부터 세계 각지에 순회했던 《떠도는 도시들》, 1999년 하랄드 제만(Harald Szeeman)의 제49회 베니스 비엔날레 본전시 등이 있다. 그 당시 세계화의 확산은 우리의 사고방식과 작업 방식, 삶의 방식에 영향

을 끼쳤고, 이제는 국제적으로 일하는 것이 거의 불가피한 일처럼 되기 시작했었는데, 1990년대 중후반에 들어오면서 나 역시 점차 세계 도처에서 장소 특정적 퍼포먼스, 설치, 영상 작업 등을 하게 되었다. -

Hou Hanru

1990년대의 전환기 동안 많은 여성 작가들이 매우 대담한 작업, 특히 퍼포먼스를 다루었다. 당시 활발히 활동하던 또 다른 여성 작가 중 이 불 등도 마찬가지이다. 이 상황에 대해서는 어떻게 생각하나? 또한, 1998년 제24회 상파울루 비엔날레에 참여한 직후, 이듬해 왜 돌연 한국을 떠나기로 결심하였나? -

Kimsooja

나를 포함한 1990년대 한국의 여성 작가들은 자신의 신체를 통해 사회적인 억압을 표출하는 퍼포먼스 작업을 많이 했다. 이는 당시 가부장적 사회에서 한국 여성이 대면하는 사회적 지위, 또 억압과 관련 있다고 생각한다. 따라서 당시 많은 여성 작가들이 페미니즘을 지향하고 있었다. 하지만 퍼포먼스 아트는 1970년대와 1980년대 이미 한국에서 해프닝이나 이벤트의 형태로 성행하고 있었는데, 대체로 AG(Avant-Garde)나 여성 작가 정강자 외에는 주로 남성 작가로 구성된 ST(Space and Time)가 주도하고 있었다. 1990년대 중반 한국 여성들은 오늘날만큼 평등한 권리를 누리지 못했고, 일반적인 여성의 일상은 유교적 가치 체계와 사회적 가부장적 힘에 의해 좌지우지되곤 했다. -

1992년부터 이듬해까지, 뉴욕 MoMA PS1의 레지던시 프로그램에 참여한 후 서울의 서미 갤러리에서 첫 개인전을 가졌다. 여기서 <바느질하며 걷기 Sewing into Walking>(1994)라는 3개의 퍼포먼스에 의한 최초의 비디오 작업과 MoMA PS1 이후 한국에서 처음으로 보따리 설치 작업을 선보였다. 이미 싸매진 보따리로 갤러리 공간을 다시 ‘감싸는’ CCTV 영상과 함께 ‘미디어 보따리’로서 TV 모니터와 보따리를 설치하고 헌 옷들을 갤러리 바닥에 깔아 관객이 그 위를 걷게 했다. 이러한 작업들은 페미니즘과 쉽게 연결할 수 있었는데, 나는 이 ‘페미니즘’이라는 타이틀을 거부해왔다. 페미니즘은 나의 보따리가 가진 형식적이고 개념적인 요소, 그리고 내가 접근하려 했던 통합과 보편성이라는 가치를 대변하기에는 적절치 않았기 때문이다. 대부분의 여성 작가들은 개인전이나 단체전에서 자신의 사회적 위치에 대한 반감을 표출했다. 여성 작가 개인으로, 이처럼 서열화된 한국 사회에서, 심지어는 국제 미술계에서조차 살아남기가 쉽지 않았던 것이 사실이다.

-

1993년 MoMA PS1 레지던시를 마치고 서울로 돌아온 후, 이러한 한국의 사회적, 문화적 이슈들을 더욱 분명하게 인지할 수 있었다. 당시 한국은 경제 발전 덕분에 사회적으로 다양하게 변하고 있었지만 1997년 시작된 경제 위기로 급속히 흔들리게 되었다. 나는 제24회 상파울루 비엔날레의 한국 대표 작가로 선정되었지만, 정부로부터 타당한 재정적 지원을 받지 못했다. 브라질의 한인 지원과 이전에 아르코(ARCO)로부터 받은 특별지원 외에, 나는 당시 한국으로부터 그 어떤 충분한 지원도 받을 수 없었다. 때문에 내가 출품하려 했던<떠도는 도시들-11,633마일 보따리 트럭 Cities on the Move-11,633 Miles Bottari Truck>(1998)을 상파울루로 운송하는 것조차 어려웠다. 이 상황이 무척 실망스러웠고, 또 나를 무기력하게 했다. 결국, 이러한 상황을 알고 개인적으로 지원해주겠다는 한국계 브라질 이민자의 도

움까지 받기에 이르렀다. 여러모로 나는 한국에서 더이상 희망이 없다고 판단했고, 가족과 생이별을 하며 결국 뉴욕으로 떠나게 된 것이다. -

지금까지도 한국 미술계는 한국을 떠나 외국에서 활발히 활동하는 작가들을 거들떠보지도 않고, 나는 한국으로부터의 소외에도 불구하고 지속적인 도움 없이 작가로서 입지를 굳혀왔다. 1990년대 후반 경제 위기 이후, 서서히 성장하던 한국의 미술시장과 저널리즘은 공공연하게, 아전인수 격으로 관객의 눈을 가리고 미술계를 왜곡해온 사실이 많았다. 작가로서 내가 걸어온 길은 정부와 갤러리로부터 지속적인 지원을 받으며 기득권을 누려온 몇몇 한국 작가들과 완전히 다르다고 할 수 있다.

-

Hou Hanru

그 당시 기존 권력에 반대하던 학생들이 몇몇 중요한 미술 운동을 전개하고 단체를 조직한 것으로 알고 있다. -

Kimsooja

민중미술이 대표적인 사례인데, 1980년대부터 난지도, 메타복스(META-VOX)같이 기존의 흐름에 반기를 든 세대와는 다른 모더니즘과 포스트 모더니즘 단체의 활동도 이어졌다. 주로 내가 수학했던 홍익대학교 출신 작가들을 중심으로 새로운 단체들이 만들어졌고, 뒤따라 뮤지 엄(MUSEUM), 타라(TARA), 로고스 & 파토스(Logos & Pathos) 등이 결성되어 활동했다. 이들 단체의 일부 구성원을 잘 알고 있었지만 나는 이런 흐름에서 완전히 독립되어 있었다. -

Hou Hanru

당시 민중미술과 당신 세대의 작가들이 개념적이고 실험적인 형태의 작업을 시도하는 새로운 경향을 드러냈는데, 특히 퍼포먼스와 설치 작품이라는 분야에서 두드러졌다. 여기서 당신은 어떤 역할을 했다고 생각하는가? -

Kimsooja

우리 세대에 앞서, 단색화 작가들과 동시대에 활동했던 AG, S.T그룹 같은 실험적이고 개념적인 미술 단체의 모더니즘 운동이 있었다. 단색화는 특히 홍익대학교 교수들을 주축으로 그 담론을 구축하며 세력을 공고히 하고 있었지만, 나는 개인적인 관계를 떠나 단색화 이론이나 활동, 그 어느 것도 따르지 않았다. 내 또래와 단색화 작가들 사이에는 큰 세대 차이가 있기도 했고. -

홍익대학교에서 1976년부터 1980년까지 학사 과정, 이후 1982년부터 1984년까지 석사 과정을 밟고 있을 때, 민중미술이 일어나기 시작했고, 이 운동을 주도하는 일부 구성원을 개인적으로 잘 알고 있었다. 지적인 차원에서 관심을 두기는 했지만, 그들이 나에게 민중운동에 동참하기를 바랐을 때 그럴 수 없었다. 왜냐하면, 나는 정치적 이슈에만 몰두하는 것에 일종의 거부감 같은 것이 있었고, 일부 정치적 미술이 내재한 공격적 측면에 공감할 수 없었다. 당시 나는 추상적이고 행위적이며, 개념적인 순수 미학을 지향하고 있었다. 지금까지도 그 어떤 단체나 집단 활동에 전혀 관심이 없다. 대학생 시절, 나는 교수, 화가 대부분이 속해 있던 단색화 그룹이 화단을 지배하다시피 하는 경향에 질문을 던지면서 여기서 나를 분리하고 독립하려고 노력했다. 또한, 동기들에게 여러 가능성과 관점을 제안하고 대화의 창구를 열기 위해 수업 시간에 의도적으로 단색화 교수들과 상반되는 의견을 피력하기도 했다. 정치적 서열, 미술계의 위계와 단절하기 위해, 또 나 자신 본연의 모습을 지키고자 자신을 완전히 고립시켜왔다. 지난하고 외로운 여정이었다. 내 퍼포먼스와 설치작업의 영향력에 관해서는, 대형의 장소 특정적인 설치작업 혹은 1990년대 말과 2000년대 초반의 글로벌한 퍼포먼스 작업이 젊은 작가들에게 영향을 끼친 것 같다. 이후 그들의 작업 규모나 재료에서, 또는 장소성에 있어 글로벌한 이슈를 다루는 것을 자주 목격해왔다. 그리고 최근 나의 관심사 중 하나로서 지속적으로 문맥화하고 있는 바느질과, 그에 연관된 바늘과 실의 관계, 거울, 싸매기, 풀기 등의 개념들이 서서히 현대미술 사조 내에서 확산되고 언어화되고 있는 것을 자주 목격한다. 특히 몸의 정체성과 직조의 방식에서.

-

Hou Hanru

사람들은 미술계를 주도하는 인물로서 당신을 이불이나 최정화 작가 같은 좀 더 젊은 세대와 자주 동일시하곤 한다. 이들은 그 시기 사회정치적 상황에 정면으로 맞서면서 유사한 입장을 표출했다고 할 수 있다. 이 불의 작업은 압제에 반대하는 일종의 보복적 성격을 띠는 반면, 당신의 작업은 명상과 초월성에 훨씬 더 가깝다. 그리고 당신은 직물이나 보따리같이 사람들이 친밀하게 느끼는 소재를 사용했다. 어떻게 이러한 조형 언어를 구사할 수 있었나? -

Kimsooja

나는 천성적으로 그 어떤 종류의 폭력이나 정제되지 않은 감정 표현을 꺼리는 사람이다. 그렇기에 지속적으로 비폭력성을 다루는 자기성찰적 작업을 해왔고, 이것이 개인과 사회에 대한 나의 입장이기도 하다. 그 어떤 정치적 이슈에도 직접 관여하지 않았고 또 그럴 수도 없었다. 내가 만들어낸 미술 언어는 언제나 치유와 관조의 관점에서 비롯했는데, 아마 폭력에 민감한 나의 취약성과 인간에 대한 연민에 기인했을 거라고 본다. -

이 취약함은 어린 시절 휴전선 근방에 살았던 나의 경험에 근간을 두고 있을지도 모르겠다. 나는 선천적으로 상처받기 쉬운 성격이고, 그 어떤 폭력적 장면도 볼 수 없다. 하지만 오랜 시간 소리 없는 저항과 인내로 내성이 생긴 것도 사실이다. 나는 대체로 주변 사람들을 포용하고 또 소통하려는 성향을 가지고 있다. 그러한 성향은 캔버스의 표면에서도 반응하며, 나를 구조적인 측면 이외에 치유를 위한 하나의 방법론으로서 바느질에 주목하게 만들지 않았나 한다. 바늘의 잠재적인 폭력성에도 불구하고. 나만의 예술 매체를 탐색하며 이 세상에 산재한 십자형의 구조들을 집요하게 주시했다. 1983년 어느 날, 어머니와 이불보를 만들었던 경험을 통해 회화의 방법론으로서 바느질을 발견했다. 어머니와 마주 앉아 뾰족한 바늘 끝으로 부드럽고 선명한 색깔을 가진 비단을 막 꿰매려던 찰나, 마치 온 우주의 에너지가 나의 몸을 통과해 바늘 끝에 닿는 것 같은 전율과 함께 놀라운 충격을 받았다. 이때 곧바로 경계와 표면, 그리고 바늘이 꿰뚫고 가는 종횡의 직물 구조와의 관계를 인지했다. 대부분의 천은 수직·수평의 패턴으로 직조되어 있는데, 나는 이를 하나의 회화로서, 표면의 구조를 탐구하는 또 하나의 방식이라고 보았다. 이러한 경험은 선천적으로 상처받기 쉽고, 주변을 감싸고 연결하고자 노력하는 나 자신을 ‘함께 엮어 직조’하는 순간이기도 했다.

-

동시에 이때는 내가 캔버스의 표면 구조에 관한 미학적 딜레마를 겪고 있었던 시기였다. 대학 생활을 시작한 후 여러 해 동안 나만의 회화적 방법론을 찾고자 노력하던 중, 일상의 천을 캔버스 삼고 바늘을 붓 삼는 바느질을 발견했던 거다. 바늘과 바느질이라는 개념은 자연스럽게 사회적, 문화적, 정치적 차원으로 확장되어 나갔고, 나의 최근 작업까지 광범위하게 확장되어 왔다.

-

Hou Hanru

이처럼 당신은 오랫동안 이불보를 싸고 풀고, 함께 여행할 뿐 아니라, 이를 설치 작업으로 전개하며 바느질 작업을 점진적으로 발전시켜왔다. 이 이불보는 짐이라기보다 함께 다니는 동료에 가까운데, 말하자면 같이 여행할 수 있는 파트너가 된 거다. 당신이 세계 이곳저곳으로 이동할 때 동반할 수 있는 하나의 삶을 갖게 된 것과 같다고 할까? 지난 몇 년간 다른 지역과 문화에서 비롯한 다양한 직물까지 다루면서 이러한 관심사를 확장해온 것처럼. 즉, 페루에서 그 지역의 여성들과 작업하고, 또 그 직물문화를 영상에 담은 <실의 궤적 I Thread Routes - Chapter I>처럼 말이다. -

Kimsooja

그렇다. 나의 최초의 영상 작품인 <실의 궤적 Thread Routes>(2010~2016) 연작은 유럽의 레이스 문화(II장), 인도의 자수와 판목 날염 문화(III장), 중국의 자수문화(IV장), 그리고 미국 원주민의 직물과 바구니 제작 문화(V장) 등을 다루었다. 조만간 아프리카에 관한 작업(VI장)을 진행하고자 한다. -

Hou Hanru

그러한 작업을 통해 당신의 이상(vision)에 새로운 문화가 더해지리라 보는데, 어떤가? -

Kimsooja

<실의 궤적>은 과거 실과 바늘, 캔버스이자 구조로서의 직물과 자연, 그리고 건축과 문화 전반에 어떻게 접근했는지를 총망라한 회고적 작업이라고 할 수 있다. 이 작업에 대한 아이디어는 2002년 벨기에 브뤼주 길거리에서 레이스를 만들고 있는 중년 여성의 손동작과 그 보빈 레이스 (bobbin lace) 기구의 움직임을 처음 보았던 때로 거슬러 올라간다. 나는 그 자리에서 이 레이스 제작을 그 지역의 남성적인 건축 구조물들과 비교 해석하며 영감을 얻었다. 하지만 이 프로젝트를 실제로 구현하는 데는 오랜 시간이 걸렸고, 결국 2010년에 16mm 필름 카메라를 사용하여 페루의 직물 문화부터 촬영하기 시작했다. 서사(narrative)가 없는 시적 다큐멘터리 필름으로, 촬영지 주변 환경에서 자연적으로 발생하는 소리와 시각적 요소만을 최소한으로 사용했다. 나는 ‘인류학적 시(anthropological poetry)’로서 이 프로젝트에 접근하고 싶었다. 그래서 전 세계 여러 직물 문화를 다루는 길고도 고요한 여정을 통하여 서로 다른 제작 방식과 문화적 유사성, 차이점을 드러내고자 했다. 카메라 렌즈를 통해 각 문화가 가진 특수성, 직물, 건축, 자연, 삶의 방식, 의상 등을 살아있는 상태로 나타내고 싶었던 거다. -

지금까지 누군가 사용했던 이불보를 작업에 사용해 온 이유는 내가 오리엔탈리즘이나 한국의 지역적 미학에만 관심을 가졌기 때문이 아니라, 한국의 이불보야말로 한국에서 살았던 내 삶의 정체성에 있어 큰 부분이었기 때문이다. 유럽인이나 미국인이 그들 지역의 재료를 사용하는 것과 다를 바가 없기에 이불보 역시 전혀 이국적이지 않다고 해야 맞다. 서구 중심적 사고가 여전히 이불보를 그런 식으로 보고 있는 것뿐이다. 보따리 작업을 위해 선택한 이 이불보라는 타블로(tableau)는 원래 몸 이외에 무엇을 싸매기 위한 천이 아니었다. 처음에 감싸는 작업 방식을 위해 이불보를 선택했던 것은 우리가 태어나고, 사랑하고, 꿈꾸고, 고통받으며, 죽어가는, 즉 삶을 압축한 하나의 ‘틀’로서, 또 우리가 몸을 누이고 쉬는 장소가 바로 ‘이부자리’이기 때문이었다. ‘이부자리’라는 이 상징적 장소는 우리의 삶 전체를 포괄하고 있는 것이다. 한국의 이불보는 강한 색채가 유난히 눈에 띄고, 때로는 매우 극단적인 보색으로 이뤄져 있는데, 어떤 미학적인 이유로 그러한 색을 선택한 것은 아니었고, 이미 그 천과 문화적 코드의 상징적 요소로 따라왔을 뿐이다. 나는 그저 이미 만들어진 것, 그리고 결혼하면서 우리 조상과 부모님이 물려 주신 것을 그대로 차용하였던 것일 뿐이다.

무언가를 싸고 푸는 방식은 1993년 어느 날 MoMA PS1 스튜디오에서 내가 만들어 놓았던 보따리 하나를 바라보다가 문득 재발견한 것이다. 그 보따리는 우리가 어느 문화권에서든지 찾아볼 수 있는 평범하고 보편적인 사물이었다. 그러나 나는 그때 그 보따리가 완전히 다른 맥락에 놓여 있음을 발견했다. 감싸진 이불보가 갖는 캔버스로서의 회화, 레디메이드, 그리고 이미 사용된 오브제(readyused object), 형상을 통합하는 과정에서 만들어진 하나의 조각으로서의 보따리를 완전히 새로운 시각으로 보게 된 것이다.

-

Hou Hanru

당신의 최근 작품 중 <앨범: 경계를 엮기 An Album: Sewing into Borderlines>(2013)는 몇 해 전 미국 연방정부(GSA)의 예술 프로그램으로 제작되었다. 이 작품은 미국과 멕시코 국경을 다루고 있는데, 처음에 당신은 미국 정부가 추방한 사람들과 작업하려 했으나 연방정부가 협조하기 어려운 부분이 있어서 미국과 멕시코 국경을 넘어 출퇴근하는 이민자들과 작업하기로 했다. -

Kimsooja

미국 국경을 넘나드는 멕시코 이민자들을 위해 이민과 관련된 개인사를 다루며 긍정적이고 포용적인 측면에 보다 집중한 작업이었다. 당시 오바마 정부는 경제 위기가 시작된 이래 작가들의 활동을 지원했다. 이민 문제가 거부보다는 환영에 가까웠을 때다. -

Hou Hanru

하지만 새로 들어선 트럼프 정부의 정책 때문에 이 문제에 관해 새로운 질문을 제기하지 않을 수 없다. 새로운 정치 구조로 인해 또 다른 상황이 주어진 거다. 이러한 변화가 당신의 작품 활동에 어떤 영향을 끼칠 것이라고 보는가? 당신은 남성들과는 매우 다른 삶과 경험을 가진 여성 이주민들에 관심을 기울여 왔다 -

Kimsooja

사실 이민 문제에서 여성은 그 중심에 있다. 여성은 모든 가족 구성원을 연결하는 가장 핵심적인 역할을 한다. 이들은 주로 기차, 자동차, 버스같이 가시적인 수단을 통해 이동하는데, 불법 이민일 경우 체포될 가능성이 높은 방식이다. 때문에 통상 3분의 1에 해당하는 이주 여성이 추방된다. 남성은 위험 요소가 더 큰 방식을 택하는데, 주로 도보로 사막을 횡단하거나 보트를 타고 간다. 심지어 국경을 넘기 위해 파놓은 지상과 해상의 터널들도 있다. 여성은 보통 다른 이들을 위해 일을 하며 점진적인 이민 방식으로 생존해간다. 예를 들어 다른 가정이나 작은 상점 등에서. 이들은 단기간 한 장소에 머물고, 일정 수익을 얻으면 다시 이동한다. -

Hou Hanru

이 프로젝트는 이민자들이 붙잡히고 구금되는 미국과 멕시코 국경 바로 위에서 전개되었다. -

Kimsooja

그렇다. 이 프로젝트는 애리조나 주의 새로 확장한 마리포사 입국장에 입항할 수 있는 입구이자 출구에 영구적으로 설치됐으며, 미국과 멕시코 국경선 바로 위에 자리 잡고 있다. 대형 LED 화면에는 출퇴근하며 매일 국경을 넘나드는 이민자들의 얼굴이 리드미컬하게 떠올라 머무르고, 또 사라진다. 심리적 여정의 시간 흐름을 보여주며 각 인물의 앞모습과 뒷모습을 촬영했는데, 내가 개개인의 이름을 부르면 카메라를 향해 돌아보는 방식이었다. 이는 그들 자신과 다른 사람 사이의 심리적 경계를 만드는데, 첫 번째 타자는 카메라, 그다음 타자는 관객이다. 나는 이들의 정신적 경계와 작품이 설치된 정치적 경계의 접점에 주목했다. -

사실 이 프로젝트를 통해 미국 이민의 현실과 멕시코인들의 삶의 조건을 더 이해하게 되었다. 트럼프 대통령의 이민 정책, 특히 멕시코에 관한 정책 때문에 사회적, 정치적, 문화적 지형도가 변했다. 우리는 새로운 시각으로 이민을 바라보아야 한다고 생각한다. 이는 현재 전 세계인들에게 매우 시급하고 중대한 사안이 되었다. 나는 지난해 멕시코 이민자들이 마주하는 새로운 현실을 리서치할 기회가 있었다. 멕시코의 여성이민협회 등 여성들의 이민을 지원하는 다양한 기관이 활동하고 있는데, 흥미로운 점은 여성이민협회가 미국의 비영리 기관의 지원을 받고 있다는 사실이다. 나는 남미, 특히 멕시코에서 이주하는 여성들이 놓인 여러 상황을 조사했다. 멕시코를 통한 이민은 끊임없이 이어지고 있고, 이민을 돕는 기관들은 억류된 가족 구성원, 여성 혹은 아이들에게 안식처를 마련해주며 교육 프로그램을 비롯한 많은 지원책을 제공하고 있다. 일반적으로는 이주 과정에서 가족은 흩어지고, 여성들은 구금되거나 멕시코로 되돌려 보내지기도 하는데, 이들의 자녀들이 미국에서 태어났다면 지원 기관들의 관리를 받을 수 있다. 아이들은 새로운

보금자리로 이동하게 되는데, 안타깝게도 불법 이민자인 어머니는 자녀를 만날 수 없다. 이후 미국인이 아이들을 입양할 수 있고 아이들의 성과 이름이 바뀐다. 그리고 이들의 생물학적 어머니들은 자녀에 대한 그 어떠한 권리도 가질 수 없게 된다. 그래서 이러한 가족들이 다시 만날 수 있도록 지원 기관들이 많은 노력을 기울인다. 이 문제는 단지 한 개인의 이민 문제로 국한되는 것이 아니라 가족과 관련된 전반적인 이슈이기도 하다. -

이민 가정 내에서 여성의 역할이 얼마나 중요한지 깨달으면서, 새로운 필름 작업에 여성을 중심 인물로 고려하기 시작했다. 새로운 멕시코 이민 프로젝트에는 여러 국기를 몸에 걸친 여성 퍼포머들이 참여할 예정이다. 과거 스페인이 멕시코를 침략했던 경로를 배경으로 하여, 멕시코 밸리의 두 화산 사이에서 퍼포먼스를 촬영할 계획이다. ‘이츠타치우아틀(Iztaccíhuatl)’과 ‘포포카테페틀(Popocatepetl)’ 화산 사이이다. 이츠타치우아틀 화산은 ‘라 무헤르 도르미다(La Mujer Dormida)’, 즉 ‘잠자는 여인’이라고도 알려져 있는데, 이 두 화산에는 멕시코인에게 잘 알려진 남녀 사이의 슬픔과 영원한 사랑을 상징하는 신화가 있다고 한다.

-

Hou Hanru

이는 분명 이민 가정을 둘러싼 특정 문제를 넘어 다양한 이슈를 아우르고 있다. 나아가 모든 이들의 관계, 혹은 가족 관계의 문제를 연구하는 것으로 확장되어야 하겠다. 이번 서울관의 전시에서는 관객이 직접 만든 찰흙 공으로 뒤덮인 커다란 타원형의 탁자를 선보였다. 이 관객 참여형 작품에 관해 설명해 줄 수 있겠나? -

Kimsooja

나는 오랫동안 세라믹에 관심을 갖고 주시해왔다. 한 번도 실제로 제작해 보진 않았지만, 용기 그 자체보다는 그릇이 만들어 내는 허 (viod)의 공간이 더욱 흥미로웠다. 2016년 리옹 현대미술관에서 열린 요코 오노(Yoko Ono)의 개인전

《여명의 빛 Lumière de l'aube》을 위해 마련된 ‘워터 이벤트(Water Event)’에 미술관 관장으로부터 초청된 적이 있다. 요코 오노는 미술가들에게 물을 담는 용기를 제작해달라고 요청했다. 당시 나는 찱흙을 만지게 되었는데, 하나의 보따리로서 우리가 살아가는 지구이자 무언가를 담는 용기로 찰흙 공을 떠올렸다. 물을 담기 위해 어떤 빈 공간을 만들기보다는, 이미 물기를 머금은 찰흙 공을 만들어 전시함으로써 환경 문제까지 다루고자 했다. 그래서 말라가고 있는 작은 찰흙 공 하나를 보냈다. 그때부터 찰흙 공의 여러 형상에 주목하며 찰흙 공을 만드는 행위가 이를 만드는 사람에게 어떠한 심리적, 명상적 영향을 끼치는지 관찰하게 되었다. 찰흙 공을 만들려면 손가락과 손바닥을 전부 중앙으로 밀며 힘을 가해야 한다. 또, 그 표면에 있는 모든 모서리 부분을 밀어 넣으며 매만져야 한다. 각진 부분을 매끄럽게 만들어야 하므로 완벽한 구 형태를 만드는 게 결코 쉬운 일은 아니다. 양쪽에서 중앙으로 힘을 가하는 행위는 이 찰흙 공에 작용하는 중력을 만들어내는 것과 흡사하다. 가장 완벽하고 매끄러운 구 형태를 만들기 위해서는 양 손바닥 사이에 찰흙 공을 굴려야 한다. 보따리를 만드는 것처럼, 두 손으로 무언가를 감싸는 행위에 가깝다고 할 수 있다. 이처럼 구를 만들기 위해 찰흙을 굴리는 행위를 반복하다 보면 마음속에 구 형상을 떠올리게 된다. 스튜디오에서 어시스턴트들과 찰흙으로 작업했을 때, 우리는 본능적으로 이 재료에 반응했고, 매우 열중하여 찰흙을 만지고 굴렸다. 이 즉각적 반응과 집중은 매우 인상적이었다. 그래서 이 작업은 나보다 참가자들에게 훨씬 중요할지도 모른다는 생각을 했다. 그래서 세계 내지는 우주를 상징하는 길이 19m의 거대한 타원형 탁자를 만들고, 관객을 그 자리에 모아 그 경험을 공유하도록 했다. 이 작품에서 참여자들은 각자의 공간과 시간을 누리지만, 어떠한 물리적 결과물과 마음의 상태에 도달하도록 함께 작업하는 프로젝트인 셈이다. 또 우주적 풍경, 마음의 우주를 만들어내면서 함께하는 공간, 공동의 커뮤니티를 창조해낸다. -

Hou Hanru

광장처럼 말인가? -

Kimsooja

그렇다. 이 거대한 타원형의 탁자는 총 68개의 불규칙적이고 기하학적 형태의 작은 탁자가 모여 이루어진 것이다. 탁자 아래에는 32개의 스피커와 16트랙의 사운드 작품 <구의 궤적 Unfolding Sphere>을 함께 설치했다. 이 작품은 완전히 마른 찰흙 공들이 구르고, 부딪혀 굴러가고, 스치는 소리를 담고 있으며, 4∼5명이 움직인 찰흙 공들이 각각의 다른 마이크에 녹음되고 편집되었다. 찰흙 공이 굴러가며 테이블의 각진 코너에 부딪힐 때 소리가 나기 때문에, 이 소리는 공의 기하학을 드러내는 셈이다. 그래서 사운드 작업의 제목도 ‘구의 궤적(Unfolding Sphere)’이라고 정했다. 공들이 큰 소리를 내며 부딪힐 때는 천둥 같은 소리, 우주적인 소리를 내기도 한다. 연이어, 오디오 퍼포먼스로써 내가 직접 물을 머금고 ‘그르르르’하며 목을 울리는 음향이 함께 편집되어 있다. 때로는 작은 시냇물이 흐르는 듯한 소리로 들리기도 하는데, 목에서 구르는 수포가 중력을 거슬러 공기를 밀어내기 때문에 움직이는 공의 수직성이 두드러지게 된다. 찰흙 공이 굴러가는 소리는 수직적인 힘이나 움직임을 갖고 있으면서도, 탁자의 수평축을 드러내게 된다. 나는 1970년대 후반부터 이와 같은 수직과 수평의 구조에 깊이 관심을 가져왔고, 이번 전시에서는 이러한 맥락에서 제작된, 나의 퍼포먼스 사진을 활용한 실크스크린 판화 작품 시리즈 〈몸의 연구 Structure-A Study on Body>(1981)도 선보인다. 이 작품에서 나는 팔을 90도로 기울여 삼각형, 원, 팔각형, 사각형 등의 기하학적 도상을 만들고 있다. 나의 신체와 그 움직임의 형태 사이에서 생성되는 기하학적 공간을 규정하기 위해 삼원색(빨강, 노랑, 파랑)을 사용했다. 이 작업들은 이후 수직·수평의 구조를 가진 나의 바느질 작업과 <바늘 여인>과도 직접 연계된다고 할 수 있다. -

Hou Hanru

우주적인 감각, 즉 신체와 세상의 연결을 언급하고 있다. 이 작업에서 흥미로운 점은 빛을 사용하면서 강조된 신체와 건축물 사이의 관계성인 것 같다. 예를 들어, 당신은 2006년 스페인의 마드리드 크리스털 궁전, 2013년 베니스 비엔날레의 한국관, 이번 국립현대미술관 전시의 설치 작업처럼, 창문에 회절격자 필름을 부착해 스펙터클한 환경을 조성해냈다. 빛이 스며들어와 무지개 효과를 만들며 내부 환경에 변화를 주면 우주 같은 느낌을 자아낸다. 베니스 비엔날레의 한국관의 <호흡: 거울 여인 Respirar–Una Mujer Espejo/To Breathe–A Mirror Woman>(2013)에서 빛과 소리가 완전히 차단된 적막한 공간이 설치되기도 했다. 이는 우주의 존재감을 나타내는 두 가지 측면 사이의 대조를 환상적으로 보여주는 거다. 최근 몇 년 사이에 전개된 새로운 작업인 것 같다. -

Kimsooja

이번 국립현대미술관 전시에도 크리스털 궁전과 베니스비엔날레에서 사용했던 필름과 같은 것을 사용했다. 이러한 작업은 회화나 안료를 빛으로 전환한 것이다. 특수 필름은 인치(inch)마다 수많은 가로, 세로의 금이 나 있어 직조된 듯한 구조를 보인다. 빛이 이 필름을 통과하면 보는 각도에 따라 색이 변하여 무지갯빛을 만들어낸다. 프리즘처럼. 이는 빛과 관련하여 내가 지속해오고 있는 회화, 캔버스, 색채, 안료의 구조에 대한 연구 중 하나이다. 나는 빛과 소리의 성질을 밝혀내기 위해 칠흑같이 어두운 절대 침묵과 암흑의 공간을 만들었다. 시각화하는 방법은 다른 작업과 정반대지만, 이 작업은 내가 삶과 예술에 내재한 이중성에 대해 던져왔던 질문들과 연결된다. 캔버스의 종횡 구조처럼 내가 이중성에 관해 제기하는 문제들은 정신적인 구조들, 우리 마음속의 만다라와도 깊은 관련이 있다. 나의 석사 논문 『조형기호의 보편성과 유전성에 관한 고찰: 십자형 기호를 중심으로』(1984)는 고대 유산부터 동시대 회화와 조각에 이르기까지 여러 작품에 나타난 십자 형태의 상징을 다룬다. 미술사 전반에 걸쳐 이 십자 형상과 구조를 찾아볼 수 있고 현재까지도 그 지속성을 발견할 수 있다는 점에서, 이러한 구조와 모티프가 창조성과 혁신성을 갈구하는 동시대 미술에 어떻게 끊이지 않고 나타날 수 있는지 참으로 궁금했다. 피에트 몬드리안 (Piet Mondrian), 카지미르 말레비치(Kazimir Malevich), 요셉 보이스(Joseph Beuys), 안토니 타피에스(Antoni Tapies), 루치오 폰타나(Lucio Fontana), 프랭크 스텔라(Frank Stella) 등을 비롯한 많은 작가들이 이러한 근본적인 십자 구조를 대면해왔다. 나 역시도 예외가 아니며, 늘 세계와 인간의 정신에 깃든 내적 구조들에 관해 질문해왔다. 석사 논문에서 십자형 구조들과 칼 융(Carl Gustav Jung)의 원형 이론(archetypes theory)을 적용하여 만다라의 심리적 기하학 관계를 밝혀내고자 했다. 이는 예술과 삶의 이중성에 관한 나의 물음들과 무관하지 않다. -

베니스 비엔날레의 빛과 암흑 공간에 대해 더 이야기하자면, 뉴욕에서 이 전시를 준비하는 동안 허리케인이 몰아닥친 일이 계기가 되었다. 일주일이 넘도록 전원이 끊긴 완전한 암흑 속에 살아야 했다. 나는 그 시기 동안 칠흙 같은 어둠 속에서 지내던 아파트 건물과 거리를 걸으며, 누군가 나를 향해 걸어올 때 공포감을 느끼곤 했다. 그리고 결국 이러한 공포감이 타인에 대한 나의 ‘무지(ignorance)’에서 비롯되었다는 것을 깨달았다. 내 마음 속에, 또 관계 속에 자리한 이 무지는 내가 작품에서 만들어낸 공간에서 경험하는 어둠과도 같고, 결국 그 무지에의 질문을 관객에게 던지는 것이었다.

-

Hou Hanru

완벽한 마무리인 것 같다. 현재 우리는 일종의 암흑 속에 살아가고 있다. 우리는 이 암흑을 헤쳐 나갈 새로운 빛을 창조해내야 한다. -

Kimsooja

정확하게 그렇다.

— Essay from Exhibition Catalogue 'Kimsooja: Archive of Mind' published by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, 2017. pp.18-85.