2024

이경진 │ 45년의 예술 여정, 아티스트 김수자의 깊고 긴 숨.

2024

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu │ Kimsooja Discusses the Intriguing Stories Behind Her Art

2024

유선애 │ Kimsooja Universe

2024

Yu Seon Ae │ Kimsooja Universe

2023

Soyeon Ahn │ Journey from point to infinity

2023

안소연 │ 점으로부터 무한으로의 여정

2023

Keumhwa Kim │ Bottari as a Fluid Canvas and Sculpture

2023

Galeries Lafayette │ Kimsooja To Breathe

2022

유선애 │ One the Spectrum: KIMSOOJA

2022

Andreson Subin │ Interview

2020

김복기 │ '바늘 여인’, 세계를 직조하다

2020

윤혜정 │ 김수자 ─ 삶과 존재를 끝없이 질문하는 개념미술가

2017

Jérôme Sans │ A Journey through Immobility

2017

Hou Hanru │ Create A New Light

2017

후 한루 │ 새로운 빛을 밝히다

2015

Thomas Van Loocke │ Kimsooja 'To Breathe' in Centre Pompidou Metz

2013

Daina Augaitis │ Kimsooja: Ways of Being

2013

김찬동 │ 2013 베니스비엔날레 한국관 출품 '보따리' 작가 김수자

2013

Franck Gautherot │ A Place to Be - A Conversation with Kimsooja

2012

Chiara Giovando │ The Unaltered Reality of the World

2012

Choi Yoonjung │ Interview

2012

최윤정 │ 인터뷰

2011

Andrew Maerkle │ Points of Convergence - Part 2: Mirror-Void-Other

2011

Andrew Maerkle │ Points of Convergence - Part I: Other-Self-World

2010

Maxa Zoller │ Interview: Woman / Needle

2010

Ryu Byounghak │To be Born, Love, Suffer and Die

2010

류병학 │'지수화풍(地水火風)’에서 생명을 보다

2009

Sunjung Kim │ An Interview with Kimsooja

2008

Kelly Gordon │ Interview with Kimsooja

2006

Oliva María Rubio │ An interview with Kimsooja

2006

Olivia Sand │ An Interview with Kimsooja

2006

Francesca Pasini │ An Interview with Kimsooja

2003

Nicolas Bouriaud │ Interview

2003

Flaminia Generi Santori │ Interview

2003

Mary Jane Jacob │ Buddha Mind/Kimsooja Conversation

2002

Olivia Sand │ Kim Sooja

2002

Gerald Matt │ A Meditation on Art and Life Kim Sooja

1998

Hans Ulrich-Obrist │ Nothing Is In-Between Kim Soo-Ja

1997

Hans Ulrich-Obrist │ Wrapping Bodies and Souls

1996

Park Young Taik │ From Plane to Three Dimensions: A Bundle Kim Soo-Ja

1996

박영택 │ Interview: 평면에서 입체로의 접근, 보따리

1994

Hwang In │ Sewing into Walking

1994

황인 │ Sewing into Walking

2024

-

이경진

지난가을 일본 후쿠오카를 방문했더군요. 그곳 우치하마 중학교 학생들과 대화하고 박수받으며 퇴장하는 영상을 봤습니다. 뭉클했어요. 약 45년간 활동해 온 예술가 입장에서 학생들에게 전하고 싶었던 말이 있었나요? -

김수자

-

제 작업을 600명의 학생에게 소개하는 자리였어요. 따뜻하고 감동적이었죠. 내게 주어진 1시간이 누군가에게는 오랫동안 남을 기억이 돼 영감을 주고 삶을 변화시킬 수 있다면 의미 있겠다는 생각을 했습니다. 조언을 해야 할 자리가 생기면 늘 꿈을 포기하지 말고 위험을 감수하라는 얘기를 합니다. 젊은 작가들을 만나도 두려워하지 말라고 하죠. 물론 분별이 있어야겠지만, 무엇보다 포기하지 않고 앞으로 가는 힘이 필요해요. 이번 경험을 통해 저도 옛 생각을 하게 됐어요. 학생 때 접했던 새로운 경험은 훨씬 오래 기억에 남는 것 같습니다. 대학에 들어가 처음 미술관에 갔던 일, 프랑스 작가 클로드 비알라(Claude Viallat)가 국립현대미술관에서 한 강의를 들었던 순간처럼요. 그보다 더 어릴 땐 아버지의 군 복무로 방방곡곡을 떠돌며 유목민 생활을 했고, 미술관 방문이나 미술과 관련된 경험이 전혀 없었습니다.

-

이경진

미술가라는 역할에 관심을 가지게 된 건 무엇 때문이었을까요? -

김수자

문학과 음악을 비롯해 여러 방면에 관심이 많았어요. 그중 미술을 택한 건 은퇴 없이 지속적으로 삶을 사유하고 반영할 수 있는 직업이라고 생각했기 때문이에요. 성악을 전공한 어머니, 작곡을 공부한 동생을 비롯해 음악인이 많은 가정이라 성악 같은 음악 분야가 저에게는 더 가까운 진로일 수도 있었죠. 하지만 성악은 신체와 나이의 한계가 있으니 전 생애에 걸쳐 예술 의지를 불태우기에는 활동 가능한 기간이 짧다고 느껴졌어요. -

이경진

긴 호흡의 예술 활동으로서 미술을 꿈꿨군요. -

김수자

항상 미술을 사색하고 응시하는 행위라고 생각했어요. 삶과 예술을 사유하는 긴 호흡의 활동으로 미술을 택했던 것 같아요. -

이경진

“삶과 예술의 토털리티(Totality)에 도달하고 싶다”고 자주 얘기해 왔어요. 미술가가 되지 않았으면 종교인이 됐을 거라는 말도 한 적 있습니다. -

김수자

특히 휴머니즘에 관심이 있었어요. 빈곤으로 고통받는 사람들, 신체적 · 정서적으로 취약하고 연약한 상태, 전쟁 혹은 어떤 부당함. 그 속에 있는 사람들을 늘 생각했습니다. 고등학교 땐 내가 따뜻한 집에서 따뜻한 밥을 먹는 데 죄책감을 느꼈어요. 그런 면에 민감했죠. 고등학교를 그만두고 채석장으로 가려는 마음도 먹었습니다. 삶의 터전에서 고통을 겪는 이들과 함께 힘듦을 나누고 도움이 되고 싶다는 생각을 많이 했고, 스스로 많이 괴로워했어요. -

이경진

괴로움을 기꺼이 겪으며 타인의 고통을 응시하게 된 계기가 있었을까요? -

김수자

글쎄요. 자연스럽게 그리 됐어요. 정현종 선생님의 시 ‘고통의 축제’ 구절이 내면에 잠재된 시절이었죠. 저는 타인의 고통 때문에 너무 고통스러웠어요. -

이경진

올해도 예술적으로 의미 있는 일이 빼곡했습니다. 대표적으로 많은 관람객이 방문한 파리 부르스 드 코메르스-피노

컬렉션에 펼친 전시가 있었죠. <엘르>는 올해를 빛낸 이름을 조명하는 ‘엘르 스타일 어워즈 2024’에서 ‘올해의 아티스트’로 선정해 무대로 모시기도 했고요. -

김수자

밀도 있는 성취감을 느낀 해였습니다. 상반기에 중요한 프로젝트를 여러 개 마쳤고, 모두 잘 구현돼 기분 좋았어요. 각 사이트에 맞게 새로운 언어를 채굴하는 작업이었죠. 사우디아라비아의 알울라 사막에 설치한 ‘To Breathe-AlUla’ 프로젝트도 그랬고, 파리 피노 컬렉션의 로툰다 홀 작업은 미니 회고전 같은 전시였기 때문에 제 작업을 관통하는 ‘보따리’ 컨셉트의 총체성을 보여줬다는 점에서 의미가 있었어요. 메츠 성당(Metz Cathedral)에 스테인드글라스로 영구 설치한 작업의 프로토타입을 다시 악셀 베르보르트에서 전시할 기회도 있었고요. 탄야 보나크다르(Tanya Bonakdar) 갤러리와 함께 20년 만에 뉴욕에서 개인전을 열어 그간 의미 있는 작업을 보여줄 수 있었습니다. -

이경진

피노 컬렉션 로툰다 홀을 채운 작품 ‘호흡-별자리 To Breathe-Constellation’는 이제껏 싸매온 ‘보따리’ 컨셉트를 건축물로 전환시킨 작업이었습니다. 그런 면에서 상징적인 레이나 소피아 크리스털 팰리스(Crystal Palace, Museo de National Reina Sofia)의 작업 ‘To Breathe-Mirror Woman’이 연상됐어요. 숨과 호흡은 김수자에게 어떤 의미인가요? -

김수자

페인터로 작업을 시작한 1970년대부터 저에겐 캔버스가 하나의 질문이었어요. 캔버스의 표면이나 구조를 고민했죠. 캔버스는 회화에 있어 대상이자, 다른 타자이자 그 자신이고, 항상 대립이 있는 대상이었어요. 정면으로 맞서면 동시에 뒷면을 꿰뚫어보고 싶은 의지를 느끼게 했죠. 캔버스의 표면은 하나의 보더(Border)이기도 하고, 벽이기도 해서 바느질이라는 방법론으로 그 깊이를 가늠하고 이어가는 작업을 1980년대 초부터 이어왔어요. 바느질에는 이원론적인 면이 있죠. 안과 밖을 들락거리고, 매스큘린하면서도 페미닌하고, 공격적인 한편으로는 치유하고, 두 개로 갈라진 틈새를 이어줍니다. 2004년 폴란드의 우치 비엔날레(Ƚódź Biennale)에서 과거 텍스타일 공장이었던 빈 공간이 저에게 주어졌습니다. 그곳에 들어서는 순간 직조 기계들의 소리가 들리는 것 같았고, 순간적으로 제 몸이 생생하게 의식됐어요. ‘숨 쉬는 일이 곧 직조 행위구나.’ -

이경진

그렇게 ‘더 위빙 팩토리(The Weaving Factory)’라는 작품을 처음으로 그 공간을 위해 선보였습니다. 다양한 속도와 강도, 깊이로 숨을 들이마시고 내쉬는 소리를 공간에 채웠어요. -

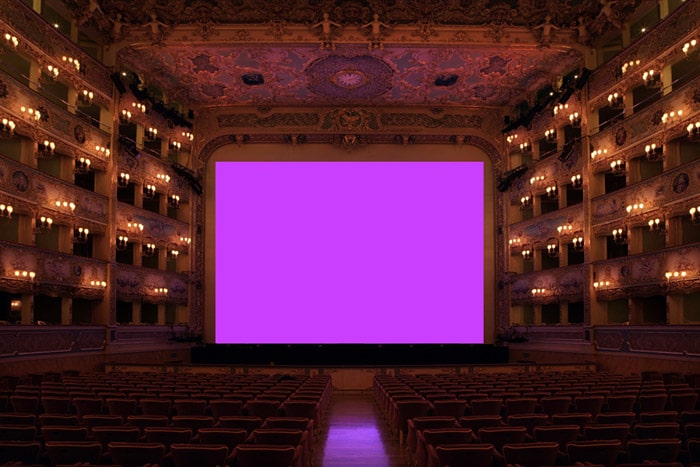

김수자

2004년의 일이에요. 이후에는 2006년 초에 베니스의 오페라 극장 라 페니체(La Fenice)가 불에 탄 뒤 다시 오픈할 때 무대 위 스크린에 프로젝션 작업 커미션을 받았어요. 그때 오페라 극장인 라 페니체의 성격을 생각했죠. 노래라는 것 역시 ‘숨’이 확장돼 발생한, 문학적 내러티브가 있는 예술 형태잖아요. 숨을 다시 연결해서 생각하게 됐습니다. 사운드를 설치하고 스크린에 비디오 프로젝션을 했는데 디지털 컬러 스펙트럼이 계속 루핑되는 화면이었어요. 제가 주목한 부분은 그 프로젝션 작업에서 과연 평면은 어디에 있는가 하는 것이었습니다. 우리의 시각, 응시하는 행위도 하나의 ‘바느질(Needling)’로 이해하게 됐습니다. 그렇게 처음으로 ‘To Breathe’라는 타이틀을 사용했어요. 같은 해 크리스털 팰리스에서 선보인 ‘To Breathe-A Mirror Woman’은 건축 공간을 하나의 보따리로 보면서 내외부 공간을 나누고, 실제와 버추얼한 이미지를 반사시키는 거울 표면, 삶과 죽음의 경계를 오가는 숨, 날숨과 들숨 같은 것을 공간에 설치한 겁니다. 숨은 무엇보다 우리 존재가 나선 여행길의 시작과 끝입니다. 숨의 지속성은 삶의 지속성과 연결돼 있습니다. 제가 발전시켜 온 삶과 세계의 이중 구조를 통한 반영. 거기에서 드러나는 해답들. 이를 넘어서는 어떤 피안의 세계. 이런 것에 던져온 질문이 ‘숨’이라는 개념과 맞닥뜨려진 것 같아요. -

이경진

피노 컬렉션에서 관객들이 ‘호흡-별자리’를 경험하는 모습도 장관이었습니다. 다양한 사람들을 작품 속으로 끌어왔고, 아마도 모든 관객은 김수자의 비밀스러운 퍼포머였겠죠. -

김수자

싸매는 행위를 하지 않고 보따리를 싼 거죠. 다만 이번에는 옷이 아니라 휴머니티로요. 제가 그걸 퍼포먼스라고 발표한 적은 한 번도 없었습니다. 관람객 각자의 개성과 프라이버시가 있기 때문이죠. 하지만 저는 그들을 한 사람 한 사람 눈여겨보며 즐겼고, 기대보다 액티브한 리액션이 나와서 사실 놀랐어요. 많은 이가 그 공간 안에서 자신의 존재성을 다시 재인식하고 가늠해 봤죠. -

이경진

이 작품으로 촉발된 새 질문이 있나요? -

김수자

로툰다 홀의 ‘호흡-별자리’ 작업을 하며 보따리 컨셉트에 연관될 수 있는 24개의 작품을 24개의 비트린(유리 전시장)에 설치했어요. 퍼포먼스도 있고, 한지를 손으로 쥐었다 펼친 작업도 있었죠. 로툰다 홀에 거울을 설치하여 발아래에 다시 돔이 시각적 ‘보이드(Void)’를 창조하였어요. 우리가 달항아리를 제작할 때 두 점의 베이스를 사용하는 것과 같죠. 두 개의 돔을 엎어 연결하는 행위가 되잖아요. 베이스와 베이스가 서로 맞닿는 경계는 바로 거울이고요. 굉장히 큰 깨달음이었어요. 경계의 만남, 어둠과 보이드의 관계, 거울과 보이드의 관계. 양자적 관계성이 지금도 큰 물음으로 남아 있어요. -

이경진

공간 요소를 새로 제작하는 작업이 아닌 주어진 공간 조건 속에서 최소한으로 개입해 최대한의 경험으로 응답한다는 입장으로 작업을 지속해 왔습니다. 이는 어떤 물음에 대한 답이었나요? 또 결국 ‘보따리’가 김수자에게 중요한 컨셉트가 될 수 있었던 첫 번째 지점은 무엇이었는지요? -

김수자

보따리는 이미 존재하는 오브제라는 점이에요. 이미 존재하는 사물의 의미를 끊임없이 채굴하고 드러내는 일이 그동안의 제 작업이었습니다. 그 근간에 결정적 영향을 준 존 케이지(John Cage)가 1985년 파리 비엔날레에서 시연한 작업을 하나 본 거죠. 그의 사운드 피스를 듣기 위해 6m 길이의 빈 컨테이너에 들어갔지만, 아무 소리도 들리지 않았어요. 측면에 적힌 간단한 구절이 있었습니다. “Que vous essayez de le faire ou pas, le son est entendu.(만드려고 하든 안 하든, 소리는 들립니다.)” 저는 완전히 충격받았어요. 이제까지 예술은 다 만드는 것이었는데, 그는 만들지 않음으로써 자신의 작업을 전했죠. 그때부터 어떻게 만들지 않고 작업할 수 있는지, 있는 것은 그대로 두되 새로운 것을 볼 수 있게 하는 일에 지속적으로 천착했죠. 최소한의 행위나 오브제를 공간에 남기지 않고 있는 그대로 보이면서 새로운 의미나 개념을 전달할 수 있는 작업을 지속해 온 거예요. -

이경진

보따리 작업은 긴 시간 다변화되고 확장돼 왔습니다. 최근 메타 페인팅 작품을 선보이고 있죠. 페인터의 지점으로 다시 회귀한 걸까요? -

김수자

페인터로 커리어를 시작했고, 실험해 왔기 때문에 항상 열정의 본질과 시작점은 페인팅에 있습니다. 보따리도 저에게 사실 하나의 페인팅이죠. 이불보 자체는 페인팅인데 싸는 행위는 퍼포먼스이고, 싸여 있는 형태는 조각이고 설치 혹은 오브제이기도 합니다. 그것 자체가 어떤 결정체로서 질문과 해답을 갖고 있어요. 메타 페인팅은 일련의 순환적 실험을 통해 다시 돌아간 지점이죠. 넓은 땅에 아마씨를 뿌렸어요. 리넨 캔버스 섬유와 린시드 오일의 재료가 되는 아마씨 오일을 얻을 수 있는 씨를 뿌리고, 수확해서 오일도 만들고, 섬유도 만들어 리넨 캔버스 천을 짰습니다. 직접 짠 것은 아니고 주변 커뮤니티의 도움을 받았죠. 다시 회화의 본질로 돌아가는 작업의 시작이었어요. 더불어 ‘만들지 않음(Non-making)’의 태도와 방향성으로 되돌아가는, 새로운 목적지이자 출발점이에요. -

이경진

오늘 저희가 만난, 서울에 마련된 작은 전시공간을 채운 이 블랙 페인팅도 같은 맥락인가요? -

김수자

리넨 캔버스는 서구 회화의 가장 중요한 재료이지요. 여기에 스프레이한 검은 안료는 그 물질성을 최대한 제거하는, 더 이상의 블랙이 없는 ‘블래키스트 블랙’에 준하는 페인팅 재료예요. 거의 리플렉션이 없는데, 수많은 레이어의 스프레이 작업을 통해 안착된 스프레이 안료들을 가까이 보면 여전히 수많은 공간이 있죠. 바늘구멍 같아요. 공간이 어떻게 바늘구멍이 될 수 있을까요? 바늘구멍은 어떻게 공간으로 이뤄질 수 있을까요? 그 어둠의 캔버스를 바닥에 세우니 작업이 묘비처럼 느껴지더라고요. 개인의 묘비명이거나 페인팅으로 이뤄진 어둠의 보따리 혹은 보따리에 들어 있는 어두운 공간인지도 모릅니다. 이 역시 뭔가를 드러내지 않고, 최소한의 행위로 새롭게 생성되는 것이 현재 가장 흥미로운 지점이에요. -

이경진

한 인터뷰에서 “결과를 빨리 보려고 하는 사람이 아니다”라고 한 적 있어요. 1999년 뉴욕으로 이주하며 문화적 망명자를 자처한 것처럼 쉽고 어려운 것이 놓인 선택의 기로에서 늘 후자를 택한 것 같습니다. -

김수자

결혼 초기에도 우리 부부는 소록도행을 택했어요. 그들과 함께 살면서 정신과 의사였던 남편은 봉사를 했고 저는 관망자로 살았죠. 인생의 선택도 마찬가지였어요. 뉴욕으로 이주하며 가족과 분리된 삶을 20년간 지속해 온 것도 같은 맥락입니다. 작가로서 판매에 관심도 없고, 작업 그 자체에만 몰두했죠. 제 성향대로 살아온 것 같아요. -

이경진

“다른 사람의 고통이 너무 고통스러워서 괴로웠다”는 말을 오래 기억할 것 같아요. 고난을 선택하고 역경에 맞서는 방식으로 살아온 삶을 통해 괴로움이 좀 덜어졌는지 궁금합니다. -

김수자

지금도 전쟁이나 기아, 폭력을 접하기란 참 힘듭니다. 근래에는 이를 작업으로 표현하는 단계에서 조금 벗어나지 않았나 생각합니다. 예전에는 광주 비엔날레에 헌사하거나, 일본에서 큰 쓰나미가 일어난 후 그곳의 옷을 가져와 보따리를 싼다든가 하면서 희생자들을 기리기 위해 헌옷과 보따리 설치미술 작업을 했어요. 이제는 이를 초월하는 상태에 관심이 많아요. 순수한 미학과 추상성을 더 좇게 되는 것 같습니다. -

이경진

약 45년의 예술 인생 내내 상업적이지 않은 영역을 걸어왔습니다. 그 치열하고 긴긴 세월을 지탱해 준 건 무엇이었나요? -

김수자

자신을 믿었던 것 같아요. 오래전 클로드 비알라가 예술은 예술적 의지나 열망, 욕망이 주도한다는 이야기를 한 적 있는데, 저도 그런 욕망을 믿는 편이에요. 보통의 일상에서는 다소 부족하지만 예술적 에너지, 나라는 존재가 우주

와 맞닥뜨리는 지점에선 신뢰가 있었죠. 그런 우주의 에너지를 믿었어요.

─ ELLE Magazine Korea, Decempber 2024, pp. 98-103.

2024

-

The world-renowned artist Kimsooja, known for her profound explorations of identity, culture, and spirituality, continues to captivate audiences with her impactful projects and thought-provoking installations. In a recent conversation, we delved into her artistic journey and career, discussing the influences that have shaped her work and the messages she wishes to convey through her art. From her unique perspectives on Korean heritage to her innovative approach to conceptual art, Kimsooja offers insights that illuminate her creative process and vision. She also shared, for the first time, some exciting details about new exhibitions she’s planning for next year.

-

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

Could you please briefly introduce yourself? -

Kimsooja

-

I am Kimsooja, a conceptual Korean artist currently living and working in Seoul.

-

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

What kind of childhood did you have that inspired you to become an artist? -

Kimsooja

My childhood inspired me more gradually, and only later in life did I become aware of how my daily life and activities of my childhood could be translated into an artistic vocabulary. In other words, rather than my childhood inspiring me to be an artist, it is now, as an artist, that I reflect back on those memories. Becoming an artist felt like it was in my blood. I grew up near the DMZ, with a nomadic lifestyle due to my father’s military service, which left me with rich sensory memories that find their way into my work. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

What are the elements of your art? -

Kimsooja

I use various media to explore concepts in unique ways. For instance, I use bed covers for “bottari” (bundles) and filming as an immaterial wrapping method, capturing the reality of humanity and nature. Each medium, from textiles to video, unfolds different dimensions of universality and broadens the concepts within each work. Physicality in my work also reveals the void and spirituality inherent in life’s ephemeral moments. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

What role do fabrics play in expressing your art? -

Kimsooja

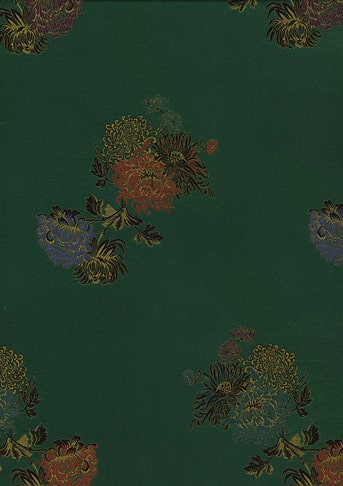

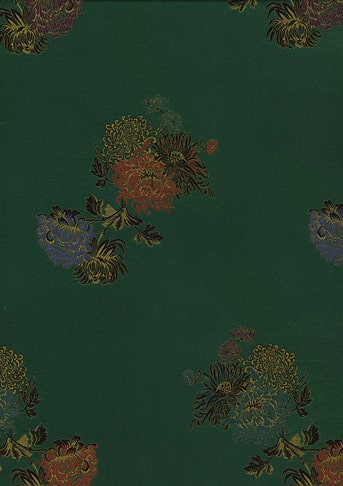

Fabrics are like a second skin, carrying bodily memories. Traditional Korean bed covers, with their symbolic embroidery and patterns, represent unfulfilled desires, love, solitude, and even death. The bed becomes a frame for existence, holding memories that resonate deeply in my work. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

Could you tell us about some important memories from your early childhood that had a defining impact on your life and views as an artist? -

Kimsooja

One day while sewing a traditional bedspread with my mother, I felt an energy surge as I observed how the needle pierced the fabric. This “revelation” pointed me toward the structural simplicity of horizontality and verticality, foundational to various life systems. It was a defining moment, showing me the deeper cross-structures in nature, mind, and artistic practice, which still influence my work. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

Your “bottari” works are quite fascinating. What inspired you to focus on “bottari” and how has this idea evolved over time? -

Kimsooja

Since working on sewing practice during the early 80s, keeping “bottari” had always been part of the scene in my studio or at home for storing small objects or fabric scraps. It got transformed into a total art form while I was at P.S.1 Studio in New York in 1992. It became a sculpture, a painting, and a performance all in one. Over time, “bottari” has grown from bundles on a truck to architectural installations like the “Crystal Palace” in Madrid. Each evolution explores new ways of wrapping and unwrapping, mirroring life’s complexity through a simple form. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

What is the story behind combining your name into a single word, from Kim Soo-Ja to “Kimsooja”? -

Kimsooja

A name often carries a deep sense of self-identity and, in my case, layers of history. My grandfather, who had hoped for a grandson, gave me the name Soo-Ja—a name with a strong, traditionally female sound in Japanese. My parents considered changing it, but ultimately respected his choice. Over time, I discovered even more meanings hidden within my name. While filming “Mumbai: A Laundry Field” in a Mumbai slum in 2007, I learned that in Hindi, the pronunciation of the word “Sooja” translates to "a needle," particularly a large, 30 cm needle used for sewing mattresses. This unexpected meaning left me speechless, almost as if I were a needle stitching together stories across cultures.

My family heritage also plays a role. The Kim clan to which I belong, specifically the "Samhyun branch," is believed to be descended from King Suro, the founder of the Gaya dynasty (45–562 CE) in southeastern Korea. King Suro married Queen Hur, an Indian princess from Ayodhya, who is credited with introducing Buddhism to Korea. Embracing the combined name "Kimsooja" allowed me to weave these fragments of history, culture, and personal identity into one unified expression. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

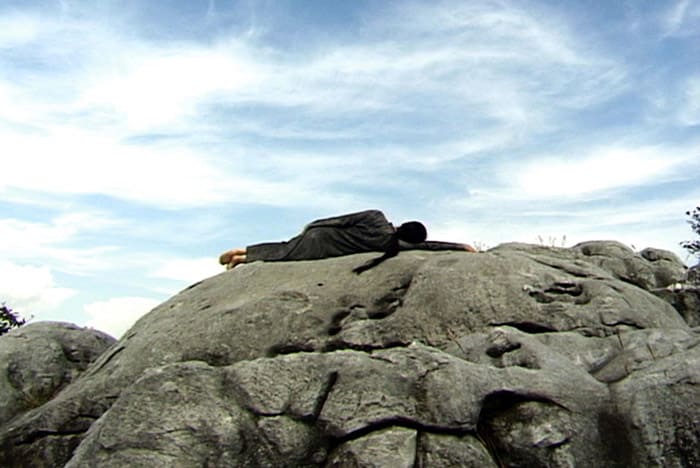

The 'A Needle Woman' video series is captivating. What emotions did you experience while shooting it, what were the biggest challenges, and how did you feel once the project was completed? -

Kimsooja

"A Needle Woman” was a series of performance videos shot from 1999 to 2009 in crowded cities worldwide, capturing my solitude amidst social conflict. Some moments were challenging, particularly in areas with strong economic or religious tensions. Witnessing humanity’s ephemerality and suffering over a long period of time and across many places was a truly transformative experience for me, filling me with compassion and broader perspectives on existence. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

How have Korean women and their stories influenced you? -

Kimsooja

For me, initially, “bottari” was just an aesthetic object, not a social one, but when I returned to Korea, I saw women’s roles as the mothers, wives or daughters under a new lens. Korean women’s resilience in the face of social constraints inspired me to work with entire used garments within “bottari”, rather than cutting them before placing them inside, revealing the realities of the human body and life stories. This allowed me to present “bottari” as something so much more than an aesthetic component. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

How did the artwork 'Archive of Mind,' which was completed with the participation of many visitors to the exhibition, come about? -

Kimsooja

“Archive of Mind” emerged from a contribution to Yoko Ono’s Water Event in 2016. I realized that shaping a clay sphere could be a communal, meditative act, where visitors could share in the experience of creation. This interactive process allowed for a collective exploration of physical, geometric, and spiritual aspects of art. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

In your piece 'To Breathe – Constellation' exhibited at the Bourse de Commerce - Pinault Collection in Paris, France, what message are you trying to convey to the diverse visitors from different ethnic backgrounds? -

Kimsooja

“To Breathe- Constellation” uses a mirror floor to create a wholeness in space, merging reality and illusion within the architecture of the marvelous dome in that space. Visitors, regardless of their background, become performers, looking, walking, sitting, posing, dancing, exploring their own reflections and engaging with existential questions in a shared, universal space. This piece dissolves boundaries, emphasizing the unity of human experience. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

What advice would you give to young artists? -

Kimsooja

My advice is to keep moving forward, taking risks confidently, no matter what challenges or untruths may exist in the art world. Trust that your art will prove itself in time, and stay true to who you are and the world you live in. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

For those who wish to study or explore art in Korea, what aspects of Korean culture and art would you recommend they look into and learn about? -

Kimsooja

Rather than focusing on specific aspects, I’d recommend fully immersing yourself in Korea—experiencing everything from its society, language, and food to its unique philosophy, humble beauty, and natural landscapes. Encounter the spirit of the “Seonbi” (a learned scholar’s ethos) and absorb the complexities and passion that define this place. It is an incredibly rich source of inspiration. -

Volga Serin Suleymanoglu

What projects are you planning for the future? Could you share a bit about them with us? -

Kimsooja

I will continue to contemplate current questions I have from different specific sites, themes of exhibitions, or biennales, exploring, answering, or questioning back to each of them. In this journey, I am planning to unveil a site-specific project for the main rotunda of the prestigious San Giorgio di Maggiore in Venice during the Venice Architecture Biennale 2025, followed by another site-specific project for the Oude Kerk, the oldest building and a church in Amsterdam, celebrating the city of Amsterdam’s 750-year anniversary, among others.

— Honorary Reporters, October 2024.

This interview took place via email in writing between August 17 and October 24.

2024

-

한 시간 남짓 대화를 나눴을 뿐인데 몸과 마음을 감싸 안아주는 듯한 경험을 한 적 있는가. 차분히 맞춰지는 눈, 낮은 목소리, 등을 쓰다듬는 손... 김수자 작가와 마주 앉으면 소란하던 사위가 고요해진다. 일찍이 ‘보따리’ 연작을 통해 싸는 행위, 감싸고 아우르는 ‘포용’을 작업의근간으로 삼아온 김수자 작가는 자신이 창조하고 행해온 작품처럼 드넓은 품과 태도로 눈 앞의 이를 어루만진다. 2년 전 서울에서 처음 만난 그를 지난 4월 파리에서 다시 만났다. 현대미술의 가장 뜨거운 현재라고 불리는 부르스 데 코메르스-피노 컬렉션(Bourse de Commerce-Pinault Collection)으로 부터 카르트 블랑슈(Carte blanche, 기획부터 실현까지 전시 전권을 아티스트에게 일임하는 것)를 부여받으며 참여한 전시 <흐르는 대로의 세상(Le monde comme il va)>이 열리는 때였다.

-

이 전시에서 작가는 부르스 데 코메르스의 가장 상징적 공간인 지름 29m, 높이 9m의 원형 홀 ‘로통드(Rotonde)’ 바닥에 4백18개의 거울을 설치해 ‘호흡 – 별자리(To Breathe – Constellation)’를 완성했다. 거울을 이용해 반원형의 천장 돔을 바닥에 반사시켜 완전한 ‘구(球)’를빚어냈다. 동그란 건축적 보따리, 달항아리 안에서 관람객은 저마다 천장과 발아래를 수차례 번갈아 보고, 산책하듯 걷기도 하고, 드러누워 하늘을 보는 등 각자의 방식으로 이 신비에 몸을 맡겼다. 그 외 로통드를 아우르는 24개의 쇼케이스에는 40여 년간 김수자 작가가 축적한 작업의 역사가 선별돼 있었다. 수십 년간 작가가 사용해 몸의 움직임이 그대로 기록된 요가 매트, 밤하늘의 별을 보고 바느질을 떠올린사진 작업, 굽는 과정에서 갈라지고 뒤틀린 모습을 그대로 품은 달항아리 등 성찰과 수행, 존재와 관계, 이해와 포용, 나눔과 공존에 골몰해온 사유의 흔적들이었다. 전시장 지하에서는 ‘바늘 여인’, ‘실의 궤적’ 등 세계의 그늘진 곳을 찾아다니며 기록한 영상 작업을 상영했다. 그야말로 김수자 작가의 결정적 순간들을 망라한 전시였다.

-

촬영을 마치고 인터뷰를 위해 그가 오랜 시간 머물고 있는 레지던시로 자리를 옮겼다. 한 사람이 누울 수 있는 단출한 침대, 책상과 의자 하나, 작은 조리대가 전부인 8평 남짓한 공간이었다. 생활을 위한 물건은 최소한으로 청빈하게 자리해 있었다. 방금 머물던 부르스 데 코메르스의 화려함과는 극명한 대조를 이루는 이 작은 방이 작가에 대해 많은 것을 이야기한다는 생각이 들었다. 한 예술가가 생에 걸쳐 차분하고도 고집스럽게 쌓아온 철학의 가장 깊은 곳을 목격한 것 같은 기분이 들었다. 일전에 만났을 때 “예술가가 아니었다면 종교인이 되지 않았을까”라고 한 말이 떠올랐다. 그와 무릎이 닿을 거리에 마주 앉아 삶과 예술을 일치시키기 위해 선택하지 않은 것들을 떠올렸다. 좁은 방에서 시작한 대화는 무한히 드넓은 곳으로 뻗어나갔다.

-

유선애

레지던시가 검박해서 놀랐습니다. 마치 종교인의 거처 같달까요. 좀 전까지 부르스 데코메르스에 머물다 와서 그런지 공간의 낙차가 더 드라마틱하게 다가옵니다. 이 작은 방이 김수자 작가의 많은 것을 설명한다는 생각이 들어요. -

김수자

실제 과거에 수도원으로 사용되었던 곳이에요.파리에 머물 때는 늘 이곳에서 지냅니다. 필요한 물건들만 최소한으로 뒀는데 불편하지 않아요. 일상을 살아가는 데 많은 게 필요하지 않은 편이에요. -

유선애

두 달 뒤면 2024 파리 올림픽이 열리죠. 파리를 찾는 세계인이 광활한 거울 정원 ‘호흡 - 별자리’를 거닐게 될 텐데요. 40년 전, 에콜 드 보자르가 주관하는 프랑스 국비 장학생으로 파리에 처음 도착했을 때의 기대에 얼마나 가까워진 건가요? -

김수자

오늘 같은 날을 기대하거나 상상하진 않았던 것 같아요. 프랑스 미술계가 제 작업에 대해 꾸준히 관심과 지지를 보내준 덕분에 작가로서 중요한 계기를 만들어올 수 있었어요. 그 도움의 시간들을 지나며 지금에 온 것인데...글쎄요. 흥미로운 건 있어요. 줄리 머레투(Julie Mehretu)와 뉴욕 할렘 갤러리에서 작가로서 첫발을 내딛었거든요. 이후 그는 상업적으로 승승장구했고, 지금 베니스 팔라초 그라시-피노 컬렉션(Palazzo Grassi-Pinault Collection)에서 개인전을 열고 있잖아요. 같은 시기에 저는 파리에 있고요. 지금까지 비상업적 공간에서의 전시나 비엔날레, 인스티튜션을 주로 떠돌며 작업 해왔는데,오늘날 세계 미술 시장을 좌지우지한다 할 피노 컬렉션에서 전시를 하는 이 상황이 아이러니하면서도 흥미로워요. 피노 컬렉션이 품는 작품의 폭이 상당히 넓다는 걸 새삼 느끼고요. 다양한 작업을 아우르는 포용성과 열린 안목을 지닌 분이죠. -

유선애

보따리를 가득 실은 트럭에 몸을 싣고 세계 곳곳을 찾아다니며 난민,이주, 전쟁, 테러 등 동시대의 폭력 앞에 두 발로 선 시간도 깁니다. 그런역사 때문인지 이번 전시는 주류 미술 시장에 최적화된 작가가 아님에도 자기 세계를 구축하다 보면 어느 순간 중심에 선다는 메시지로도 다가옵니다. 그래서 더 고무적이고요. -

김수자

저 역시 이 전시를 통해 젊은 작가들에게도 희망의 여지가 전해졌으면 해요. 많은 작가들이 상업적으로 자신을 알리기 위해 초조해하고 번민하는 것을 목격할 때가 있어요. 어떻게 보면 저는 상업화의 반대 방향으로만 걸어왔잖아요. 조급해하지 않아도 된다고 이야기해주고 싶고요. -

유선애

미술계뿐만 아니라 오늘을 사는 청년들에게도 필요한 이야기입니다. -

김수자

삶의 가치라는 것은 특정한 물질로 손쉽게 얻을 수 있는 게 아니잖아요. 물론 그 역시 손쉽다고 할 수도 없지만. -

유선애

돌이켜보면 김수자 작가의 보폭이나 걸음의 방향은 늘 같았습니다. 재료와 방법을 실험하며 방대한 작업을 해나가면서도 전시의 규모나 명성에 치우치지 않고, 필요한 자리에 섰습니다. 필연적으로 주류 미술계의 반응이나 화답이 있지 않은 순간도 있었을텐데요. 외롭진 않으셨나요? -

김수자

세간의 관심보다는 전시마다 내게 주어진 질문에 적절하게답할 수 있으면 되는 것이라 생각해왔어요. 장소나 시간, 주제와방법 등에 대해 최대치의 사색 끝에 던지는 한마디의 답을 세상에 제시할 수 있다면 그것으로 충분했어요. 그 외적인 것들에는크게 관심이 없었어요. 지금도 마찬가지고요. 그래서 함께 작업해온 큐레이터들에게 감사해요. 작가는 비엔날레를 통해 동시대의가장 첨예한 질문과 주제를 건네받게 되는데 이를 고민하며 저역시 발전해왔죠. 장소 특정적 작업을 시작하면서부터는 특정 장소에서 할 수 있는 접근 방법이나 최선의 솔루션을 찾는 데 심혈을 기울였기 때문에 그 과정을 거치며 나아갈 수 있었어요. 찾아가고 알아가는 와중에도 마음 안에 분명한 건 있었어요. 작업 과정의 노력들이 어느 순간 종합적으로 나타날 것이라는 믿음이 있었죠. -

유선애

과정 중임을 인식하는 것이 긴 호흡을 갖게 한 것이죠? -

김수자

그렇죠. 저는결과를 빨리 보려고 하는 사람은 아니에요, 절대로. -

유선애

전시를 앞두고 미술관으로부터 작가에게 전시의 기획부터 실현까지 전권을 부여하는 카르트 블랑슈를 제안받았습니다. 흔치 않은 특권입니다. 이 기회를 허투루 쓰지 않으셨을 것 같은데요. 무엇을, 어떻게 펼치고자 했나요? -

김수자

작가에게 전권을 부여하는 건 전적으로 신뢰한다는의미잖아요. 영광스러운 동시에 책임이 따르는 일이고요. 전시의중심이 되는 로통드관은 거울을 이용해 건축적 보따리로 풀어내고자 했습니다. 바닥에 설치한 거울이 돔을 비추며 발아래 시각적인 돔을 만드는 거죠. 관람객을 천상과 천하, 그 중간 세계 어딘가에 놓고자 했어요. ‘nowhere’인 것이죠. 어디도 아닌 곳. 지상인지 지하인지 모를 곳을 그저 부유하는, 중력이 사라진 공간처럼도 느껴지도록요. 그리고 로통드 관을 24개의 쇼케이스로 둘러싸, 지금까지 보따리를 배회하며 던졌던 질문들의 흔적을 선별해전시했습니다. 로통드가 몸통이라면 쇼케이스는 손과 발의 형상인 거죠. 24개의 쇼케이스를 통해 제가 지금까지 다양한 매체와방법론을 통해 같은 질문을 끊임없이 달리 해석하고 시도해왔음을 느끼실 수 있을 것 같습니다. -

유선애

20여 년 전부터 거울을 도구로 다른 차원을 열어왔습니다. 시작은 1999년 제48회 베니스 비엔날레였죠. 당시를 기억하시나요? -

김수자

‘망명의 보따리 트럭(d’APERTutto or Bottari Truck in Exile)’이라는 작품이었어요. 보따리를 실은 2.5톤 트럭 전면에 거울을 설치했는데이는 당시 코소보 전쟁(1999년 유고슬라비아 연방공화국의 알바니아계 코소보 주민과 세르비아 정부군 간에 벌어진 전쟁) 난민들에게 헌정하는 작업이었습니다. 트럭 앞에 놓인 거울을 하나의 출구로 제시하고자 했어요. 반사 효과를 통해 거울 뒤로 보이는 모든 공간을 감싸는 의미로 트럭이 한 번 더 싸이고, 다시 싸이는 작업을 했습니다. 그게 시작이었어요. -

유선애

이후 거울을 사용해 공간의 무한성, 접힘과 열림, 채움과 비움 등을 꾸준히 탐구해왔습니다. 보따리로 시작된 ‘구’의 형태는 작가에게 중요한 개념이자 키워드이고요. 이번 전시를 통해 작가의 주요 개념들이 단 한작품 안에서 집대성 됐습니다. 어떤 경로로 개념들이 모이게 되었나요? -

김수자

지금까지 거울을 통해 공간을 반사함으로써 하나의 정체성을, 총체성을 갖는 공간을 선보이고자 했습니다. 특히 이번 공간은 돔이라는 명확하고 명쾌한 형태를 지니고 있기에 구를 만들고자 하는바람이 자연스럽게 일었죠. 구 형태를 완성하는 과정에서 느낀 건 ‘연역적 오브제 보따리(Detective Object-Bottari)’라는 제목으로 달항아리를 보따리로 개념화한 세라믹, 테라코타 작업을 했었는데 이번 작업을 하면서 돔 아래 거울을 놓는 것이 마치 달항아리를 만들 때 두 개의 반원을 뒤집어 엎는 작업과의 동일성이 있다는 것을 발견했어요. 한데 이를 사전에 계산하고 작업한 건 아니었거든요. 계속해서 질문을 품으며 작업하다 보니 다르다고 여겼던 두 작업이 만나게 된 거죠. -

유선애

개념적으로는 파악하지 못했지만 행함으로써 알게 되는 사실이 있는거죠? -

김수자

제 작업 대부분이 그래요. 바느질, 감싸기 컨셉트나 그것이다시 보따리가 돼 삼차원적 바느질로 재해석되는 것, 바늘과 몸의관계 등 사전에 철저히 개념화해 시작한 작업이 아니에요. 직관적인 논리의 감각이라 해야 할까요. 직관과 예술적 충동으로 실행한것 같지만 그 안에는 저조차도 인식하지 못한 규율이 이미 존재했던 거죠. 행함으로써 나를 발견해왔어요. 지나고 나서 규율들이 보이고 한데 꿰어지는 거죠. 이 작업을 왜 시작했고, 어떻게 하게 되었는지를요. 어떻게 보면 자연의 이치를 따라가고 있다는 생각이 들어요. -

유선애

무엇보다 흥미로운 건 관람객들입니다. 10명 남짓한 어린이 관람객들은 손을 잡고 둥글게 서서 하늘과 땅을 번갈아 보기도 하고, 어떤 관객은 편안히 누워 있더군요. 공원의 한 풍경처럼 느껴졌어요. 각자 방식으로 작품을 감상하는 관객을 품는 포용성도 느껴지는 작업입니다. -

김수자

‘크리스털 팔라스’ 작업을 할 때 부터 관객을 제 작업의 퍼포머라고생각하고 있었어요. 공식적으로 이야기하진 않았지만 저 혼자서 그분들을 ‘비밀스러운 퍼포머’라 상정한 거죠. 그래서 이번 전시역시 즐기는 마음으로 관람객들을 보고 있습니다. 한 사람의 동작 하나하나를, 어떤 만남과 어긋남 같은 것들, 혹은 나르시시스트적인 반응들을요. 그리고 위로만 보던 천장을 발아래로 골똘히 보다 보면 ‘여기가 어디지?’, ‘내가 이렇게도 보일 수 있네?’ 하는 질문들이 만들어지기도 하잖아요. 그 모습들을 보며 저에게도 새로운 질문이 생겼어요. 천상과 천하의 세계, 그 중간 지점은 절단면이기도, 연결선이기도, 공간이기도 하고 허(虛)이기도 하잖아요. 과연 그것이 무엇인지를 하나씩 해부하는 과정에서 흥미로운 전개가 만들어질 수 있겠다는 기대도 있어요. -

유선애

소재도 방법도 다른 와중에 작가의 작품은 공통된 개념을 예리하게 통과합니다. 작가의 작품을 두고 ‘영적이다’라고 이야기하는 것도 이런 이유에서고요. -

김수자

나를 둘러싼 우주의 진동과 흐름, 빛과 어둠 등 자연의 현상을 감지하고 반응하고 흡수하는 모든 과정이 어떤 계시처럼 다가옴을 느끼는 순간도 있어요. 그렇다면 이런 순간들을 어떻게 만났는가 하면, 글쎄요. 그냥 오는 것 같아요. 직관과 예술적충동으로 길을 찾아가다 보면 모든 것이 하나로 만나는 접점이 있어요. 그렇게 길을 찾아가는 과정에도 분명한 목표는 있어요. 삶과 예술의 토털리티(totality)에 도달하고 싶다’고 수십 년 전부터 이야기했어요. 그 총체성이 어디에 있는지, 무엇인지 알 수는 없지만. -

유선애

삶과 예술을 이분화 하지 않았던 것이죠. 삶의 일관됨이 작업의 일관됨과도 연결됨을 느끼십니까? -

김수자

느끼죠. 내가 사는 삶이 결국 내 작업을결정할 거라는 것은 알고 있었어요. 그렇기 때문에 삶을 가치 있게 살아내고자 했어요. 그만큼 예술이 내게 중요했고, 예술이 중요한 만큼 삶을 견디고 지키려 했어요. -

유선애

그래서일까요. 김수자 작가의 작업에는 예술과 인간, 세계를 바라보는 작가의 시선과 태도가 진실되게 담겨 있습니다. 이번 전시에서 만날수 있는 2백 50장의 한지를 수평과 수직을 맞춰 쌓아 올린 작품 ‘Meta Painting’은 시간이라는 비물질을 생생하게 우리 눈앞에 보여주죠. 눈에 보이지 않는 가치가 홀대받는 지금, 작가의 작업이 더 깊게 다가옵니다. -

김수자

‘Meta Painting’에는 수많은 시간의 축적이 보이잖아요. 그 가운데 노동이 보이고요. 우리가 보는 것 이상의 것을 보는 거예요.이런 작업들을 해오는 저 또한 행하는 과정에서 보는 것 이상을봅니다. 이제 뭔가가 좀 보이는 것 같다 싶어요. 나아가 나의 어떤생각에 대해 그게 틀린 생각만은 아닐 거라는 확신도 생기고요. -

유선애

예술가로 살아온 지 40여 년이 지난 지금... 보인다는 말씀이시죠? -

김수자

하나씩 교감하고, 스스로를 검증하면서 깨닫게 되는 것들이죠. 한데 이것이 명징하게 인과적으로 해석되거나 직선적으로 인식된다기보다는 굉장히 복합적이고 입체적인 모습으로 다가와요. 내가어디에서 어떤 질문을 하고 답을 해도 이제는 내가 표현하고자한 것에 다다를 수 있을 거라는 생각이 들어요. 그래서 자유로워요. 어떤 재료든, 어느 장소에서든, 무엇을 하더라도 자유롭게 펼칠 수 있을 거라는 생각이 지금 들어요. 겁이 좀 없어졌다고 해야하나? 조심스러웠던 부분도 있는데 지금은 하고 싶은 대로 하면될 것 같아요. 물론 하고 싶은 대로 하고 살았지만. (웃음) 그런 때가 온 것 같아요. -

유선애

난민, 이주, 전쟁, 테러 등 시대적 폭력 상황에 민감하게 반응했고, 이는 곧 작업으로 이어졌습니다. 20세기를 치열하게 건너온 작가님에게 여쭙고 싶어요. 세계가 나아지고 있다고 믿나요? -

김수자

삶의 향유 면에서는 발전하고 있을지 모르지만 인간성 자체의 휴머니티는 퇴보하고 있죠. 이 세상에는 공존을 위해 노력하고, 치유를 위한 창조를 하는 이들이 존재하는가 하면 공존을 방해하는 파괴적인 부류의 사람들도 반드시 있죠. 인간의 이중성만큼이나 사회 역시 양분돼 있어요. 이는 인류가 지닌 불치의 병이 아닐까 싶다가도 그럼에도 노력하는 것 외에는 방법이 없다고 봅니다. 얼마 전, 사우디아라비아에서 열린 <Desert ×AlUla 2024>라는 프로젝트에 긴 고민 끝에 참여했어요. 나를 결단하게 한 건 ‘부끄러운 역사가 없는 국가는 없다’는 사실이었습니다. 대부분의 국가는 인류에 반하는 행위를 했죠. 그 프로젝트는 예술과 문화를 통해 과오를 개선하고 치유해 나가려는 노력을 아주 적극적으로 하고 있는 사례라 여겼어요. 내 쪽에서 레드 라인을 그으며 그들의 노력을 꺾어서는 안 되겠다는 생각이 들더군요. 그보다는 한 발 힘을 주는 것이 더 옳은 태도겠죠. 완벽한 평화와 공존에 이르지 못한다 하더라도 우리가해야 할 일이 아닌가 싶어요. -

유선애

인간 안에 내재되어 있는 희망이 있다면 그것은 무엇이라 보십니까. 우린 무엇을 갖고 있고, 우리에게 무엇을 기대할 수 있을까요? -

김수자

사랑만큼 중요한 가치가 또 있을까요. 사랑이 어떻게 발아되는지는 모르겠어요. 실을 엮듯 사랑이라는 감각과 느낌, 이성적 사고나 판단력,그로 인한 행위 등 수많은 망들이 마치 인다라망(因陀羅網, 불교에서 세상을 바라보는 관점. 온 세상을 덮고 있는 거대한 그물로각 그물코마다 구슬이 달려 있어 서로 연결되고, 동시에 서로를비춘다)처럼 섬세히 조합되고 빛을 만들며 신비한 세계를 이루는것 같아요. 그게 사랑의 본질 같아요. 왜 우리는 ‘사랑’ 하면 하나의 사랑이 가슴으로 턱 하고 뭉뚱그려져 전체로서 다가오잖아요.하지만 사랑 그 자체는 굉장히 복합적이고 총체적인 미세한 과정을 통해 인식하지 못하는 사이에 우리에게 전달되는 것 같아요.타인을 사랑한다는 건 그래서 기적이에요. 분석 하기엔 너무나 어려운 마음의 상태이자 인간이 가질 수 있는 가장 최상의 마음 상태 아닐까요. -

유선애

마무리할까요. 김수자 작가 하면 뒷모습으로 기억됩니다. 세계의 그늘을 찾아 정면으로 직시하던 모습을요. 지금은 어디를 바라보고, 향하고 있나요? -

김수자

점점 죽음의 실체에 대한 생각을 많이 하게 됩니다. 나아가 내 몸과 죽음에 대해서도 생각하고요. 내가 모르는 미래 속으로 어느 순간 들어가게 된다는 것을요. 죽음으로 인한 변화는 또다른 형태의 삶이겠죠. 또 다른 형태의 빛과 그림자인 거예요. 그빛과 그림자를 내가 어떻게 바라보고 해석하고 풀어내야 하는지가 지금의 가장 큰 과제입니다. -

유선애

무수히 많은 경계를 바느질하고 이어왔는데, 삶과 죽음을 잇는 작업을생각하고 계시군요. -

김수자

맞아요. 날숨과 들숨을 반복하다 그것이 멎는순간 끝나는 거잖아요. 끊임없이 바느질을 이어가다 멈추는 것.인터뷰의 마무리가 너무 새드한가?(웃음) 한데 정말 의미 있는 작업을 남길 수 있다면 죽음은 두렵지 않아요. 앎에 대한 열망이 유난히 커서 그럴까. 작업은 곧 앎의 표현이잖아요. 더 정확히는 앎과 모름의 표현이죠. 이 앎이라는 게 지식이 아니라 어떻게 자신과 세계를 이해하는가, 자기의 시각에서 해석하는가인 것 같아요.내가 어떻게 삶을 바라보고 해석하고 표현하는가인데 이를 미술이라는 매체를 빌려 이야기하는 것이죠. -

유선애

지금껏 앎의 과정에서 무수한 도전들이 있었음에도 이를 놓지 않은 이유이지요? -

김수자

되레 그럴수록 더 강해져요. 도전의 순간에 더 예술적충동이 일어나죠. 행복할 때, 좋은 기운으로 작업할 수도 있지만작가로서 결정적인 순간은 도전과 역경 속에서 만들어집니다. 지금까지 그래 왔어요. 그래서 흥미로워요. 도전과 그로 인한 예술적 충동 속에 드러나는 우주의 진실, 트루스(truth)를 목격하는것이 흥미롭고, 자꾸만 빠져들어가는 것 같아요. 모르면서 하고,모르면서 또 하면서.(웃음)

— Marie Claire, August, 2024. pp.40 -65.

2024

-

Have you ever experienced the sensation of being embraced in a conversation of one hour, despite having just met? When sitting across from Kimsooja, tranquility seems to fall over the surrounding noise, brought about by a calm gaze, a soft voice, and a gentle touch… Kimsooja, who from the start of her early ‘Bottari’ series (whose title references a Korean fabric-wrapped bundle) has made the act of wrapping and encompassing a core element of her artistic practice, embraces those in front of her with a vast and open demeanor, as do her creations. I first met her in Seoul two years ago and saw her again in Paris last April. The exhibition <Le monde comme il va (The World As It Goes)> was taking place, in which Kimsooja was participating after being granted a carte blanche (conferring full authority over an exhibition’s curation and realization) by the highly esteemed Pinault Collection at the Bourse de Commerce.

-

In this exhibition, the artist installed 418 mirrors on the floor of the 29 meter wide, 9 meter high Rotunda, the most symbolic space of Bourse de Commerce, for her work <To Breathe—Constellation>. Through the construction of a perfect sphere formed by reflecting the dome of the semi-circular ceiling onto the floor, visitors strolling through the architecture of the round bottari created by the artist could either gaze upwards or at their feet, surrendering their bodies to spatial mystery. In addition, 24 showcases encircling the Rotunda displayed a selection of the artist’s works accumulated over the course of her career, including yoga mats embedded with decades of the artist’s movements, photographs inspired by stitching while observing the night sky, and moon jars cracked and distorted from the firing process—traces of reflection and practice, existence and relationships, understanding and embracing, sharing and coexistence. In the basement of the exhibition space were video works recorded in tragic and unlucky corners of the world, such as and

. It was truly an exhibition that encompassed the decisive moments of Kimsooja’s career. -

After the shoot we relocated to the residency for an interview, where she had been staying for a long time. Her space was a modest room with only a single-sized bed, a desk with a chair, and a small cooking counter. Living essentials were minimal and frugally arranged. In stark contrast to the grandeur of the Bourse de Commerce, the room seemed to speak volumes about the artist. It felt like witnessing the deepest part of an artist’s philosophy, built stoically and stubbornly over a lifetime. I recalled her statement when we first met, “If I were not an artist, I might have become a religious person.” Sitting knee-to-knee across from each other, I reflected on the things she had not chosen in her effort to align her life with her art. The conversation that began in the narrow room expanded into boundless realms.

-

Yu Seon Ae

I was surprised by the ascetic simplicity of the residency. Perhaps this impression was heightened by the fact that I have just come from witnessing the opulence of the Bourse de Commerce, but this modest place seems to explain much about you. -

Kimsooja

It was actually a place formerly used as a monastery. When I stay in Paris, I always stay here. I have only the essentials, but it’s not uncomfortable. I don’t need much for daily life. -

Yu Seon Ae

In two months, the 2024 Paris Olympics will be held. The world will stroll through the vast mirror garden that is the installation <To Breathe—Constellation>. How close have you come to your expectations from when you first arrived in Paris 40 years ago under a French government scholarship at the École des Beaux-Arts? -

Kimsooja

I don’t think I ever anticipated or imagined a day like today. Thanks to the continued interest and support of the French art world, I was able to reach significant milestones as an artist. I have reached this point through those beneficial times. One interesting thing to note is that Julie Mehretu started her career at the Harlem Gallery in New York around the same time I first met her in Paris. She went on to flourish commercially and now has a solo exhibition at the Palazzo Grassi of the Pinault Collection in Venice, while at the same time I am in Paris. Until now, I have worked largely in non-commercial exhibitions, biennales, and institutions, so the situation of exhibiting in the Pinault Collection, which is said to command today’s global art market, is ironic yet fascinating. I am experiencing the diverse works in the Pinault Collection for the first time, and it possesses a great openness and inclusivity. -

Yu Seon Ae

Traveling around the world with a truck loaded with bottari, you have faced the violence of contemporary history, addressing issues surrounding refugees, migration, war, and terrorism. Perhaps because of this, the current exhibition comes across as an encouraging message that even if an artist is not optimized for the mainstream art market, they can find themselves at the center of their own world-building. -

Kimsooja

I hope this exhibition conveys hope to young artists as well. I often see many artists becoming anxious and distressed as they try to commercialize themselves. In some ways, I have only walked in the opposite direction from commercialization. I want to tell them that there is no need to rush. -

Yu Seon Ae

This seems to be a message not only for the art world but also for today’s youth. -

Kimsooja

The value of life is not something that can easily be obtained by a particular material. Indeed, assigning value to anything through material means is itself challenging. -

Yu Seon Ae

Looking back, your steps have always aligned. Even while experimenting extensively with materials and methods, you have remained faithful to yourself without being swayed by the scale or fame of the exhibition. There must have been moments when the mainstream art world’s responses to your work were not forthcoming. Did you ever feel lonely? -

Kimsooja

I have always thought it sufficient if I could appropriately answer the questions posed to me in each exhibition, rather than focusing on public attention. If I could present a single answer to the world after the utmost contemplation on the location, time, subject, and method, that was enough for me. I wasn’t very interested in external matters. This remains the same to this day. I am grateful to the curators I have worked with; through biennales, artists are given the most pressing questions and topics of contemporary times, and, as a result, I have developed as an artist. Since starting site-specific work, I have put significant effort into finding the appropriate approach or solution for individual locations, and that process has allowed me to grow. Even while seeking and discovering, there has always been a clear belief within me that effort in the process will comprehensively manifest at some point. -

Yu Seon Ae

Has recognizing the process allowed you to be patient or think long-term? -

Kimsooja

Yes. I am not someone who tries to see results quickly, not at all. -

Yu Seon Ae

Before the exhibition you were granted a carte blanche by the museum, which is a rare privilege—I’m sure you didn’t take it lightly. What did you want to see unfold with this opportunity? -

Kimsooja

Being granted a carte blanche signifies complete trust in the artist. It is an honor, but it also comes with responsibility. For the center of the exhibition, I wanted to transform the Rotunda into an architectural bottari using mirrors. The mirrors installed on the floor reflect the dome to create the illusion of a visual dome beneath the feet as well. The intention was to place the viewer somewhere between the heavens and the earth, in a liminal space that is neither here nor there, a “nowhere,” a floating space sans gravity. Surrounding the Rotunda with 24 showcases, I displayed traces of the questions I have raised in the past through bottari. If the Rotunda represents the torso, the showcases are like hands and feet. Through the 24 showcases, you can sense that I have continuously reinterpreted and sought answers to the same inquiries through various media and methodologies. -

Yu Seon Ae

For over 20 years, you have opened doors to other dimensions using mirrors. It started with the 48th Venice Biennale in 1999. Do you remember that time? -

Kimsooja

It was a work titled “d’APERTutto or Bottari Truck in Exile”. I installed mirrors in front of a 2.5-ton truck loaded with bottari, as a tribute to refugees of the Kosovo War (between the Albanian Kosovan residents and Serbian government forces). The mirror facing the truck was intended to symbolize an exit. Through the reflective illusion, the truck was enveloped once more in the space within the mirror. That was the beginning. -

Yu Seon Ae

Since then, you have continuously explored the infinity of space—folding and unfolding, filling and emptying—through mirrors. The form of the sphere, which began with the bottari, is an important concept and keyword for you. In this exhibition, the main themes are consolidated into a single work. How did these ideas come together? -

Kimsooja

Until now, I attempted to present places with a single identity and totality by reflecting space through mirrors. In particular, this place, with its clear and definite dome shape, naturally inspired the desire to create a sphere. During the process of completing the spherical shape, I realized that placing a mirror under the dome bore a similarity to the process of creating a moon jar, which I had previously conceptualized as a bundle in my ceramic and terracotta work titled “Deductive Object—Bottari”. I discovered this similarity by accident, without prior calculation or intent. As I continued working and questioning, I discovered that what I had previously considered two different processes had come together. -

Yu Seon Ae

Is it true that you come to understand things through practice rather than conceptualization? -

Kimsooja

Yes, most of my work follows this process. The acts of sewing, wrapping, and their reinterpretation into three-dimensional stitching in the form of bundles, or the relationship between needles and bodies, were not explicit concepts before starting. It’s more of an intuitive logic. However, although it may seem like I act on intuition and artistic impulse, there was already an unconscious discipline present; I discover myself through action. Afterwards, the disciplines become apparent and interconnected. I reflect on why I started and how I arrived at it. In a way, it feels like following the principles of nature. -

Yu Seon Ae

What is most fascinating is the audience. I noticed that about a dozen young children stood in a circle holding hands, alternating their gaze between the sky and the ground, while some visitors lay down comfortably. It felt like a scene in a park. The work seems to embrace viewers in their own ways of experiencing it. -

Kimsooja

Since my work for the Palacio de Cristal, I have considered the audience as performers in my work. Although I haven’t formally stated this, I think of them as secret performers, so to speak. Therefore, I watch the visitors with a mindset of enjoying the experience. Each person’s movements, interactions, and even displays of narcissism are observed. When viewers who usually look up at the ceiling focus on the ground instead, they start to wonder, “Where am I?” or “Can I look this way too?” Seeing these responses, I too find new questions arising. The midpoint between the heavenly realm and the earth is a section, a connection, a space, and even a void. I hope that an intriguing development will emerge from the process of dissecting what that is. -

Yu Seon Ae

Despite your use of diverse materials and methods in your practice, your works are meticulously strung together by related concepts. Perhaps this contributes to why many ascribe a sense of spirituality to your work. -

Kimsooja

Moments when I sense and respond to the vibrations and swirls of the universe, the phenomena of light and darkness, sometimes feel like revelations. As for how I encounter these moments, they seem to simply emerge. As I navigate with intuition and artistic impulse, everything meets at a point of unity. There is a clear goal in the process of finding that path. For decades, I’ve said I want to reach the totality of life and art. I can’t know exactly what or where that totality is. -

Yu Seon Ae

It seems that you have never polarized life and art as discrete binary realms. Do you feel that this consistency in your life reflects the consistency in your work? -

Kimsooja

Yes. I’ve always known that my life would ultimately determine my work. Because of what art means to me, I have endeavored just as much to protect and treat my life with value. -

Yu Seon Ae

Perhaps this is why your work seems to disclose a sincere perspective and attitude toward art and humanity. The work , which piles 250 sheets of Hanji paper aligned horizontally and vertically, vividly embodies the immateriality of time. At a moment when unseen values are neglected, this work resonates even more profoundly. -

Kimsooja

shows the accumulation of time and labor. It allows us to see beyond what we observe. Through the process of making such works, I feel that I am also starting to see beyond the apparent and gain confidence that my thoughts might not be entirely wrong. -

Yu Seon Ae

Following an artistic career of over 40 years—do you mean to say that your vision is clearer? -

Kimsooja

Yes, I’m discovering things through meticulous interaction and self-validation. However, this realization does not present itself in a clear, causal, or linear way but rather in a very complex and three-dimensional manner. I feel that wherever I ask questions and provide answers, I can reach what I want to express. Therefore, I feel free. I believe that I can freely unfold my work with any material, at any location, and in any way. Maybe I’ve become less fearful? There used to be aspects where I had my reservations, but now I feel I can do as I wish. Of course, I’ve always done what I wanted [laughs]. It feels like the time to do so has come. -

Yu Seon Ae

You have been sensitive to issues regarding refugees, migration, war, and terrorism, which has translated into your work. Having lived intensely through the 20th century, do you believe the world is improving? -

Kimsooja

In terms of enjoying life there may be progress, but humanity itself is regressing. There are those who strive for coexistence and healing and those who disrupt coexistence. Like the duality of humanity, society too is divided. Our situation may be an incurable disease, but still, the only way is to continue striving. Recently, I participated in the Desert X AlUla 2024 project in Saudi Arabia after much deliberation. What prompted my decision was the fact that no nation is without shameful history. Most nations have committed acts against humanity. I viewed this project as a proactive effort to improve and heal mistakes through art and culture. I thought it was right not to undermine their efforts but rather to support them. Even if perfect peace and coexistence are not achieved, this endeavor seems like something we must do. -

Yu Seon Ae

If there is inherent hope within humans, what would it be? What do we have, and what can we expect from ourselves? -

Kimsooja

Is there a value more important than love? I don’t know how love germinates. Like weaving threads, the sense and feeling of love, rational thinking or judgment, and the resulting actions seem to intricately combine and create a mysterious world, like Indra’s net (a Buddhist concept where the world is covered by a vast net with pearls at each intersection, reflecting and illuminating each other). That seems to be the essence of love. When we think of “love,” it often appears as a unified feeling in our hearts. Yet love itself is very complex and conveyed to us through intricate processes we don’t consciously recognize. Loving others is, therefore, a miracle. It is an incredibly challenging state of mind and perhaps the highest state of human consciousness. -

Yu Seon Ae

Shall we conclude our interview? The image of the artist Kimsooja evokes for me an image of you facing the world’s shadows. What are you looking at now, and what are you aiming for? -

Kimsooja

I increasingly contemplate the reality of death, as well as my own body and death, entering into an unknown future. Changes due to death will be another form of life, another form of light and shadow. The biggest task now is how I interpret and unravel that light and shadow. -

Yu Seon Ae

You have sewn together countless boundaries, and now you aim to merge life and death. -

Kimsooja

Yes. The act of breathing in and out repeats until it stops, like the act of sewing before halting. Is the ending of the interview too sad? [laughs] But if I can leave behind a truly meaningful work, death isn’t frightening. Maybe it’s because of my strong desire for knowledge. Work is an expression of knowledge. More precisely, it’s an expression of knowledge and ignorance. Knowledge isn’t just about information but about understanding oneself and the world and interpreting from one’s perspective. It’s about expressing how I see and interpret life through the medium of art. -

Yu Seon Ae

Is that why you haven’t let go of the knowledge process despite countless obstacles? -

Kimsooja

The more challenges I face, the stronger I become. Artistic impulse arises more in moments of opposition. While happiness and positive energy can influence my work, the decisive moments as an artist are formed through adversity. That has been the case so far. The truths of the universe revealed through challenges and artistic impulse seem to captivate me. I keep acting without conscious knowledge again and again [laughs].

— Marie Claire, August, 2024.

Journey from point to infinity

Interview by Soyeon Ahn (Artistic Director, Atelier Hermès)

2023

A laboratory of light: diverse lives in a space embraced by light

Soyeon Ahn

─ It has been my great pleasure to witness the entire process of your work for almost 40 years. From the first time I saw your work in a group exhibition in the late 1980s, to the dialogues we had during our visits to MoMA PS1 in the early 1990s. I still remember vividly the time we spent together thinking about and working on “The Tiger's Tail” exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1995, with Mr. Nam June Paik’s support.

Your work is characterized by an exceptionally meditative and intense energy that evokes a strong sense of empathy and comfort in the viewer. Above all, each of your works has a life force that continues to change with the passage of time. For example, your artworks from the 1980s and 1990s that reflect particular issues of the time can still be reread today as a contemporary work; same artwork can be reinterpreted from many different perspectives depending on the interests of the exhibition organizers, which I believe is the unique power your artworks possess. I am drawn to this process that starts with the needle meeting the fabric or object, leading to the issues of human network created by the act of sewing, wherein the notions of movement and envelopment of the bottari (fabric bundles) extend conceptually, beyond the human world and into the universe with nature and light. In attempting to provide an overarching definition to your work, one might describe it as a “journey from point to infinity.”

The world of your work is so contemporary and comprehensive that there is little point in mentioning the temporality of each piece. So perhaps let us begin today's dialogue with a recent project that you have been tackling, and take a trip through time more freely? Among your ongoing projects, I would like to start with your work Weaving the Light (2023), which is installed in the Cisternerne at the Frederiksberg Museum in Copenhagen. I heard that you introduced light into a space with no natural light at all, since the exhibition venue is a former underground water reservoir. Please tell us about your production process.

Kimsooja

I had never worked in the dark without light, creating light and reacting to it. This time, I had to work in an old underground reservoir called Cisternerne, which is about 4,400 square meters in size and divided into three underground chambers, and it is a special space where water always maintains 100 percent humidity. Of course, we could have drained all the water out, but we did not.

When I went down into the first basement space, the floor was wet and it was very humid, the second basement was full of water compared to the first room, and the third basement was full of water. I saw the darkness, the water as a mirror, and these three basement spaces as a whole as a spectrum of experience. I wondered how I could fully interpret and materialize the situation and give the audience something special to experience. As a result, I came up with the idea of bringing artificial light into the darkness, which I had never used before.

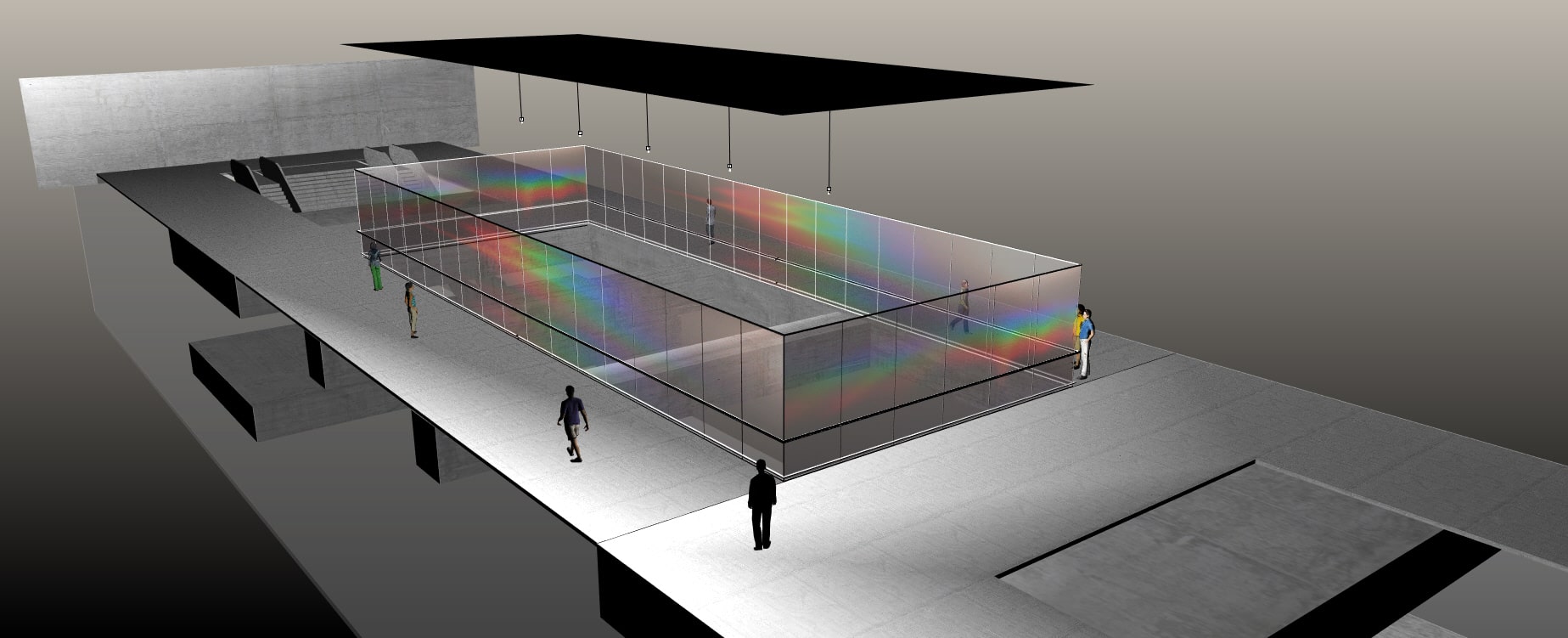

Until then, rather than creating new architectural elements such as objects or new spaces, I had worked with the attitude of a minimal intervention to given spatial conditions, responding with the maximum possible experience. The spatial form of the Cisternerne was the same as that of the CAPC Museum of Contemporary Art in Bordeaux, France, with arched brick walls. Within this dark space, I suspended acrylic panels, which are tableaus of light, throughout the arched architectural space. I had used diffraction grating films before on arched structures with glass windows, which we didn’t have this time. So instead of glass windows, I installed a total of 48 large acrylic panels to which I adhered diffraction grating films. We used different light sources for each space and position, and by slightly adjusting the angle and intensity of the light, we created spectra of lights that interacted with one another. In a sense, I considered the entire space as a single laboratory of light.

In this laboratory of light, I tried to create a space that would gradually expand the audience's experience from the starting point to the third basement. The second basement space is filled with 10 to 20 centimeters of water, so a wooden walkway was constructed to allow visitors to reach the water's edge and view a rainbow feast of light diffused on the surface of the water by a mirror-like effect as they walk by the films.

The space always has a 100 percent humidity, and because it’s very cold in winter and there is a lot of water, it was quite a challenge to install electric lighting. However, even under the most difficult spatial conditions, the project’s success exceeded my expectations, thanks to the wealth of experience of the site crew. I feel that this project is the culmination of all my past work in expression of light, but also marks a new chapter.

Soyeon Ahn

─ It is very interesting to see this new step forward in a project that uses artificial light, a laboratory of light. We can expect even more in the future.

Kimsooja

What is also special is that I conceptualized this work and titled the exhibition "Weaving the Light." This was the concept from which this project developed. In the course of my work over the past 40 years, I have developed and experimented with sewing, weaving, and wrapping, which are all acts related to textiles; it was done through breathing, looking, and walking, as well as the everyday act of domestic labor. This time, I tried to visualize light as an act of weaving. The light actually weaves itself, but I personified the weaving subject as if I (or the audience) were weaving and creating the light, and connected it to the spectra of lights, the shape and function of the needle, so that the audience can have a proactive experience within the space.

Soyeon Ahn

─ Your previous artworks had mainly used natural lighting, which makes it more of an encounter with uncontrollable situations, created by the artist’s direction and the actual natural light that is constantly changing. As with the concept of a "laboratory of light," I get the impression that with this artwork you have begun to intervene more actively, bringing light artificially into places where there is no light, weaving and creating, so to speak.

Kimsooja

Controlling the light is a new element, and I am particularly fascinated by the unintended movements of the audience created through this process, and the moment when an infinite language of light is born through performances.

Soyeon Ahn

─ It’s great to hear about your new experiments. Looking back at your artworks from the past, you have treated "light" as a very important medium. There are other artists that deal with "light," but usually the expression takes some kind of form or shape. Your artworks, on the other hand, are formless, based on the interrelationship between light and space. Here, you took the windows of the architecture as an opportunity for the visitors to see the inside and outside spaces as a whole. I think that through light, you give a vision of infinite functionality; could you tell us a little more about what led you to work with light, and your thoughts on light?

Kimsooja

In fact, I first attempted the transition from color to light in 2003, when I used theater lighting for the first time in a collaborative project at The Kitchen, an art space in New York. Since then, I have continued to do so through video projections, which recreate theater lighting in a portable format.

At this "Spotlight Readings" at The Kitchen, organized by Linda Jablonski, the original stage lighting for To Breathe - Invisible Mirror / Invisible Needle was screen-projected for the first time as a stage piece. Before this work, I had introduced light bulbs for the first time in Deductive Object, an early work I created at MoMA's PS1 studio that used objects such as cloth, ladders, and a pasta machine. In “The Tiger's Tail” exhibition we participated together, I inserted a piece of fabric into a hole in the wall of the old warehouse, as both color and substance; installed a bottari piece in the corner of the room; and left a fluorescent light propped up on the wall.

After that, I created To Breathe - A Mirror woman (2006/08) at the Crystal Palace (Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía) using natural light combined with diffraction grating film for the first time. The foundation of all the work of the painting, derived from the crisscrossed surface and structure of the warp and weft threads of the canvas cloth, was transformed into rainbow light through the prism of the nanoscale crisscrossed scratches of the grating film, which for me was the very moment when the fundamental question of painting arose. It was a turning point, and in a sense, from that moment on, my work expanded in concept and dimension from color to light.

My use of grating film is also related to the cross symbols that represent the vertical and horizontal as planes, in terms of the structure of the world, language, and spirit, which I was constantly thinking about and exploring in the late 1970s and early 1980s. I carefully observed and studied Korean architecture, furniture, the structures of the Hangul, and various manifestations of nature. I even wrote my masters thesis on them. It all accumulated for me to consider more deeply the question of flatness, as well as the surface and structure in painting.

Within a centimeter of the diffraction grating film, there are approximately 5,000 vertical and horizontal scratches on an almost nano scale, which diffract light as soon as it reaches the surface, becoming transparent and reflecting to create streaks of light in five different colors. I think it was inevitable that my long-pursued questions regarding structures of the world and the plane led me to the expression of light using diffraction grating films. My journey into light began at that point. So, I would say that the light used by other artists and my use of light have very different contexts. I treated light as a fundamental structure and material more so in the art historical context.

The opportunity at the Crystal Palace was more of a decisive blow, in that I applied to an architectural structure the expressive technique of bottari (wrapping objects with fabric into bundles), which I had already repeated for some time. My perception is that, by wrapping a vacant space, the light encounters the lives of the performers, which in turn makes the artwork embrace the various lives of the people that are living with us.

Sewing and weaving: to breathe and to live

Soyeon Ahn

─ In addition to extending the concept of weaving and using new materials and architectural structures, you have also set forth the premise of "To Breathe" in your work. You have emphasized this premise, seeing the physical space as connected to life, opening the possibility to breathe and feel together in the physical space. Can you tell us about how you have come to explore the concept of "To Breathe"?

Kimsooja

I used grating film because I saw it as a fabric, and therefore conceptually suited for the expression of bottari, or wrapping things with fabric.

In short, I incorporated the concept of "breathing," the incessant intersection of inhalation and exhalation. We consider death to be the moment when the breath ceases, so to speak. So, similarly to sewing and knitting, in incorporating breathing as a phenomenon that traverse boundaries, artworks come to connect life and death, or self and others.

In my work, which always expands dimensions and concepts as vertical and horizontal space, the issue of duality is an important axis that is constantly evolving. Duality I mean here does not end as such, but rather is infinitely generated, transformed, annihilated, mutated, and reinterpreted, which in turn creates different worlds. So, ideas usually come to me suddenly, like a bolt of lightning, and brings about a conceptual evolution in my perception of duality.

Soyeon Ahn

─ Your work inherently has a very universal message, which may feel distant from life as each of us imagine it. Nevertheless, your expression is connected to the realities of life, as if it to live and breathe on its own right. As in "A Needle Woman" series, you the artist give the concept of "breathing" to the artwork, which turns the space itself into a sort of an organism, seemingly involving even the lives of those who experience the artwork.

Kimsooja

To return again to my graduate thesis, which I wrote in the early 1980s; I wrote about the universality and heritability of symbols of verticality and horizontality, as well as cross symbols. I was very intrigued because I had seen how so many artists had worked with the cross symbols in the contemporary art world ever since the emergence of modernism. I researched why so many artists, including myself, came across the cross symbol at some point in their lives, despite contemporary art being about pursuit of originality and uniqueness. This led me to the mandala, the original form of the mind, proposed by Carl Gustav Jung. I applied this concept not only to psychological aspects but also to the plastic arts. In other words, I came to the conclusion that, since the prototype of our mind is a cross-shaped form, we inevitably encounter cross-shaped forms when we strive to reach the essence.

The title of the work "To Breathe" is the result of the simultaneous development of this metaphysical approach and material interpretation in the production process. In the same context, I thought that the bottari work, with its flatness of the cloth and the three-dimensionality of the shape wrapped inside, could convey a metaphysical and material interpretation as an object that incorporates the birth and death of our bodies, our memories, and the joys of life. Through these questions, I believe I have been able to bring the audience and the work closer together. Once again, I can express my attitude toward life and forms of expression through this thought shift: "Weaving is breathing and breathing is living.”

Soyeon Ahn

─ May I ask you a personal question? Your partner, who recently passed away, was a psychiatrist, and I know you two had many conversations with and inspired each other. When I was at the PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art, he once came to see my exhibition alone and left a copy of Classic of Mountains and Seas [Shan-hai Ching] with me. Given how interested he was in art, did you ever discuss your thoughts on the human and the universe, the vertical and the horizontal?

Kimsooja

It is true that we have had a great deal of dialogue over the years, but we first met when I was writing my master’s thesis. At that time, we did not discuss art in detail. I think he had very few opportunities to experience art. However, he always lived with the essential questions of life, body, and spirit in mind.

One of my older works, Deductive Object - Remembrance (1991), consists of a small piece of old cloth, tied in a circle on a wooden staff used in hand-stitched rugs for Buddhist monks to sit on for their meditations; propped up against a steel frame with circle decorations, covered with bandages. When my husband saw it, he decided to fully believe in my art and said, "I'm going to use this as a textbook for my psychiatry.”

Soyeon Ahn

─ I am sure that for him, you were someone who could visualize the concepts he had. Your artworks do not reflect any particular religion, but at the same time, they are intricately intertwined with religious elements. The artworks you mentioned, which deal with light, by nature seem to have links with the tradition of stained-glass, since they utilize the glass windows provided in the architecture. I also heard that you created the stained-glass windows for Metz Cathedral in France. I assume that this was a very special experience, distinct from making artworks for an exhibition.

Kimsooja

It was a great honor to be asked to create the permanent stained-glass windows for Metz Cathedral, known as one of the most beautiful cathedrals in France. At the same time, it was a very historic space, so I was under a lot of pressure when it came to making the work.

At first, I tried to create an experimental work with nanopolymer. However, when I actually placed the materials temporarily in the space, the distance from the audience was too great, and it was difficult to show the beauty of the details and the movement of light of the nanostructures. Above all, the cathedral is as an institution that makes decisions based on managing historical concepts, which values and must protect tradition at all costs. So, it was also difficult to get approval to use the new nanopolymer material. In the end, I proposed the alternative of using hand-crafted ancient glass and the newly developed dichroic glass together. This resulted in a better solution than using fragile nanopolymer-encrusted glass, since the dichroic glass emitted a rainbow of colors and changed its appearance as the visitors moved around. It also presented a new way of expression that was different from the classical stained glass, which all meant a lot to me. It was also significant for me because it presented a new way of expression different from classical stained glass. The French atelier Parot, which produced the stained glass, was the team that restored Notre Dame Cathedral. It was a great experience to work with the best collaborators in the production process. At the same time, it was an opportunity for me to introduce glass as a new material in my work. I continue to be inspired by the use of glass and am experimenting with it.

This project was carried out in a Catholic cathedral, but in fact, I would like to understand all religions. Of course, cathedrals feel like a familiar and friendly space to me, as both my and my husband’s families are Catholics for generations, and I attended Catholic schools for a time. However, in deciding on the color of the stained glass, I still applied the five colors of Obangsaek. It is a color system that originally appears in Taoism, Confucianism, and even Buddhism, and represents directions and dimensions. The encounter between Obangsaek and the cathedral is an interesting one, between the rainbow of the West and the colors of the East.

Furthermore, the glass windows of the cathedral were diamond-shaped, which is very meaningful to me, because in Buddhism, the diamond shape symbolizes the completed ego. This juxtaposition of multiple elements according to my own interpretation is a radical approach to a cathedral as a historical monument, but the cathedral was very accepting of it.

Soyeon Ahn

─ In the same way, you used the Obangsaek colors in your work Solarescope (2019), which was installed in Notre Dame Cathedral as part of the exhibition "Traversées / Kimsooja" (2019) in Poitiers, France. My understanding was that Obangsaek has an aspect of embracing matters that intrinsically cannot coexist. Our discussion has reminded me of the work Lotus: Zone of Zero (2011), which you and I installed in front of the Gates of Hell at the PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art. Sounds were emitted from a huge burning Buddha hanging from the ceiling, and you played chants of various religions in unison, right?

Kimsooja

Yes, that's right. Lotus: Zone of Zero at the PLATEAU, Samsung Museum of Art, played Tibetan Buddhist chants, Gregorian chants, and Islamic chants simultaneously, and visually showed a mandala-like burning Buddha. In a sense, it showed the tolerant attitude of Buddhism. The work expresses the hope that all religions will be reconciled and turn to an ideal world. The work was also made after the world was shaken drastically by many wars and conflicts caused due to religions. It was our message of coexistence and peace for all peoples of the world.

The work at Poitiers began with Solarescope, a projection mapping of the exterior walls of a war-torn and ruined building in gradually changing colors in all five directions, which was first shown at the 2nd Valencia Biennial in 2003. “Solarescope" means "knowledge of the earth”. By projecting light onto the walls of the building and emphasizing the walls, the intention was to draw attention to the existence of other spaces and to show the coexistence of the bifurcated spaces. This was my initial intention, but after the presentation at Notre Dame Cathedral, I made a donation so that the film would be shown every Christmas.

Soyeon Ahn

─ Your artwork Earth - Water - Fire - Air (2009), which debuted at Atelier Hermes in Seoul in 2010, was the first instance where your work with light expanded from a space of limited scale to an unlimited one. It was one of your most fundamental artworks, yet one that encompasses your practice to date, as it deals with nature itself, or the four elements of nature. The titles of each of the four elements (earth, water, fire, and wind) were embedded with deep meanings, and you presented how the four elements weave and interweave with each other.

Kimsooja

Yes, the four elements are the concept that water is not just water and fire is not just fire. They are in an interrelated dynamic, like how water always relies on fire, leaning on the wind, and depends on the earth. As the Buddhist theory of karma tells us, they are one, but they do not exist as one.

For example, I thought about water and earth in this way. First, there is water, namely the sea, which is constantly filled with still water. Then, as I look at it, I think of a mountainous landscape and find the existence of the earth there. This contemplation has developed into a concept that illustrates the relationship between nature and matter, which is important to my work.

Needles and Bottari: The Contraction and Expansion of Life

Soyeon Ahn

─ While engaging in a dialogue about light, space, and nature, I can't help but think of the needle and bottari (fabric bundles) that reflects the core philosophy of your practice. You have already mentioned it in numerous interviews, but I would like to talk about the needle and the bottari, the starting point and the core idea for your work. The atmosphere of the Korean art academy in the 1980s was rather insular, standardized and male-centered. What was it that led you to your current practice? Please tell us about what the circumstances were like when you first started out as a young artist.

Kimsooja

From the mid-1970s to the early 1980s, I attended Hongik University and its graduate school. At that time, professors associated with the Dansaekhwa movement had strong influences at the university, which meant I was also influenced by them. On the other hand, I had been experimenting in more avant-garde work since the late 1970s, making performative photographs through my body. I was very active in presenting alternative perspectives on certain issues, asking questions, and occasionally raising issues at the university, which in part influenced my work and the work of my peers.

At the time, I was also attempting to interpret my concerns and questions about the world, as well as my interest in the structure of the two-dimensional plane, through all aspects of my life. At the same time, I experimented with a variety of materials, wondering how I could express myself in my own language, a language that had never been used in art history before. But I could not find a sense of unity between my will and the medium or methodology. One day, while sewing a bed cover with my mother, I had a breakthrough encounter with the needle and thread.

As I have mentioned in other interviews, the moment the needle finally reached the soft fabric, I truly felt a shiver as if the energies of the entire universe were hitting me over the head and riding my fingertips to the very end of that fabric and needle. That moment when the needle and the sky met was exactly the starting point for confronting all the structural issues, including vertical and horizontal, that I had been struggling with for so long. Then I said, "Oh, this is it!" I had an epiphany and started doing needlework. In doing the needlework, I very impulsively and spontaneously went to the process of wrapping objects, or bottari, which in fact developed intuitively. I was not thinking of a concept or anticipating a result, but was driven by an energy that said, "I have to do it," and I immersed myself in bottari intuitively.

For example, there is a ring-shaped work entitled "Untitled" (1991). I used bent, square frames that form the circles as a canvas. The interconnection of the canvases created a ring, which became a structure that sewed or wrapped the space. This developed into the bottari.

In fact, the idea of using bottari did not come from the wrapping I was already doing in my work. But rather, one day I saw some bottari lying around that inspired me. As I continued to work with bottari, I realized that my continued expression of wrapping was, in a sense, the same in nature as bottari, which is wrapping with fabric. That is, I came to the realization that the act of wrapping objects with fabric is, after all, the same as needlework. Since needlework is the act of wrapping a flat surface that is fabric, I thought that it could also be applied to wrapping objects.

In other words, everything began as a combination of the specific energy of the time and my personal experience, but at the same time I realized that there was a definite structural logic that had been transformed to make it all happen. All of this has made the core of my practice and become the source of my work, and I believe that works such as the "To Breathe" series came to take place.

Soyeon Ahn

─ In fact, there was a major change of direction in the history of Korean art through the 1970s to the 1980s. Unlike today, where diversity is the order of the day, there was a major trend toward Dansaekhwa, a modernist form in Korea at the time, but it was supplanted by popular art in the 1980s. It was a time when even the major currents in art were overshadowed by other currents, and it was almost impossible to try something different. In your case, I think you have consistently been concerned about and rebelled against the limitations of modernism and found a breakthrough, but you were not swallowed up by the great patriarchal current of popular art. Popular art played a role in reflecting the spirit of the times, but it also failed to offer any alternatives for the art world. You, on the other hand, have sympathized with the spirit of the new era, such as the currents of feminism and nomadism, while incorporating them into artistic forms you have been developing for a long time. I think that is why you have followed a very meaningful path as an artist.

Kimsooja

I am very resistant not only to popular art, but also to collective flows and actions, which does not suit my temperament. In fact, I collaborated with some of the core members of the popular art movement when I was in college, right at the beginning of the movement. In the end, however, I chose to work alone. When I was at university, I was of course influenced by Dansaekhwa and the male-centered atmosphere, but I think that my experience with the Korean avant-garde movement and my continued interest in experimental art, as well as my participation in activities such as independent exhibitions, made this decision possible. And I was able to keep myself from the Dansaekhwa professors and artists to bring in younger artists to follow their path, because I could not see Dansaekhwa itself as a global and universal expression. I valued the experimental and avant-garde attitude in art. That being said, it is true that the two axes of Dansaekhwa and popular art have had a real influence on the Korean art world. So, I had no choice but to follow my own, solitary path.

Soyeon Ahn

─ So the monotonous atmosphere of the art world brought a sense of rebellion out of you as an artist, which led to an opportunity to seek your own path. You said that you did not come up with the idea of using bottari from the act of wrapping, but rather got inspired by "seeing" what was already there. Perhaps that is why you always give the title Deductive Object to your bottari and related artworks. Could you elaborate on why you gave them that title?

Kimsooja

Actually, I first used the title Deductive Object in the early 1990s in the process of creating the wrapping series. At the time, I was interested in discovering cross structures in things like farm tools, everyday objects, and at my home, and the wrapping process was a reaffirmation of those structures. I used this title, Deductive Object, in the way of reaffirming, rather than transforming, structures, and returning them to their original form again.

There are many bottari in my studio. But it was the moment when I happened to look down in my MoMA PS1 studio and saw a red bottari, that I began recognizing them as avant-garde objects. There had been many of them around me before that, but I guess I had not been able to recognize them that way. The bottari was a one I had wrapped to carry something, but at that moment I discovered its surprising meaning and formal elements.

Soyeon Ahn

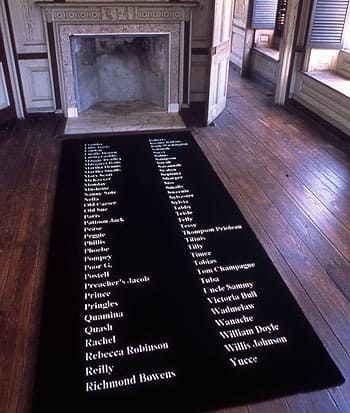

─ I think that the bottari have a meaning in themselves as finished objects, but they also have the quality of expanding the surface of contact with the audience through the act of bundling and unfolding them. You have also done several performances in which the audience can participate, but each one has a different aspect. At the first Gwangju Biennial in 1995, the scattered bottari and clothes on the hill, dedicated to the victims of the Gwangju Uprising, left such a powerful impression on me that I am still emotionally moved to this day. On the other hand, at the Setagaya Art Museum, and other museums overseas, a more fun image is highlighted, such as the coffee tables wrapped in large bedding cover fabrics. In "MMCA Hyundai Motor Series 2016: KimSooja-Archive of Mind" (Seoul), the audience was encouraged to actively participate in the exhibition further more, where some parts of artworks were made by the audience. I am curious to know what the audience means to you.

Kimsooja

Before I answer your question, let me first explain about the bedding covers I used for the particular bottari. The bedding covers used for the coffee tables at the Setagaya Art Museum are commonly used by newlyweds in Korea, and I used mainly discarded ones. Speaking of which, the bedding covers are made of eye-catching, bright colors, and the complementary color contrasts make the colors stand out even more from each other, creating a spectacle of color. The covers also contain Chinese characters and numbers symbolizing things like longevity, love, happiness, wealth, and fertility, as well as symbols of the happiness we experience in life, such as flowers, butterflies, deer, and lucky purses. This is a heartfelt gift typically from the bride’s mother, but in reality life does not always work out like that. It can be a bundle of regrets instead. Life is not always beautiful, glamorous, and happy, so even though the bottari cloth is glamorous on the outside, it has its own contradictions. In fact, the bedding covers on the coffee table at the Setagaya Art Museum can be seen as a presentation of the contradictory reality of life.

At the same time, I presented on the same single plane some things that are forbidden together – like eating in a bedroom – as a painting. I developed the concept of invisible wrapping, by associating people's activities of meeting, eating, and interacting with each other in a rectangular space as if it were visible. I thought of the bottari as frames for life. The wrapping and unfolding of bottari is akin to how our lives fold and unfold.