2006

Oliva María Rubio │ An interview with Kimsooja

2006

Petra Kapš │ Kimsooja - A One-Word Name Is An Anarchist's Name

2006

Olivia Sand │ An Interview with Kimsooja

2006

올리바 마리아 루비오 │ 김수자: 레스 이즈 모어(Less is More)

2006

Oliva María Rubio │ Kimsooja: Less is More

2006

Francesca Pasini │ Making Space

2006

Francesca Pasini │ An Interview with Kimsooja

2006

안젤라 베테세 │ 호흡

2006

Angela Vettese │ To Breathe / Respirar

2006

엘레노어 하트니 │ 현재를 살며, 우주와 이어지다

2006

Eleanor Heartney │ Living in the Present, Connecting with the Universe

To Breathe / Respirare. Palacio de Cristal. Parque del Retiro, Madrid.

To Breathe / Respirare. Palacio de Cristal. Parque del Retiro, Madrid.

An interview with Kimsooja

2006

-

Kimsooja (Taegu, Korea in 1957) is one of the most acclaimed Korean artists in the international artistic panorama. Currently, she lives and works in New York. Her works have been exhibited at biennials such as Venice, Whitney (New York), Lyon, Kwangju (Korea), as well as in the most relevant museums around the world. In our country, she has participated in important exhibitions such as Mujeres que hablan de mujeres included in the program of Fotonoviembre (Tenerife, 2001), PhotoEspaña, Valencia Biennial in 2002, MUSAC (2005), among others. She makes installations, photographs, performances, videos and site specific projects, the most recent of which was presented in Madrid's Palacio de Cristal: To Breathe: A Mirror Woman. Not long before, she had presented another site-specific project at the Teatro La Fenice in Venice. Since 1993, one of the most distinguishable elements in her work are the bottari, a kind of bundle made of traditional Korean lively colored bedcovers, which is often used for packing old clothes. Nomadism is a key subject for her, but she also tackles issues such as the relation with the other and the feminine roles, revealing not only the importance of the human being in the chaotic world we are living in but also her loneliness and fugacity.

-

Oliva María Rubio

Studying your work over time, we can say that it is a very singular work. Nevertheless, you are always dealing with present issues, such as nomadism or the relationship with the others. What are the sources of your work? -

Kimsooja

I guess the reason why my work has been engaged to present issues, regardless of a continuous singular context, is because I've been questioning old and fundamental issues on art and life. All human activities and problems come from the same root, which are old questions that have no answer, and endlessly repeat in history in one form or another. When we are planted in our own root, one can grow naturally from one's own source without trying to search another resources branches of temporary issues come out of this root in the end. -

Oliva María Rubio

Has this singularity anything to do with an education such as yours, where Asian ways of thinking are mixed with the Western philosophy Christianity, Zen Buddhism, Confucianism, Shamanism and Taoism? -

Kimsooja

In general, the complicated religious background in Korean society might confuse one's identity rather than keeping it in singular mind. It seems to be more connected with one's personality and individual history rather than social tendency. I can say that I wanted to be firmly rooted in my own culture and my own perspectives. I noticed many Korean artists in my generation were imitating and easily adopting Western practices and philosophies without question, just by reading magazines and books. At that time, in the late 80's, I decided to stop reading for almost a decade. This allowed me to question, by myself, issues on art, and to pull out ideas from my own self, rather than exterior resources. Another reason I stopped reading books was that there were so many things to read in the world besides books and magazines life and nature. My mind was always active reading all of the visible and invisible world. -

Oliva María Rubio

The bottari and the Korean traditional bedspreads with lively colours are characteristic elements of your work and have a strong presence in your installations. What do these elements represent for you? -

Kimsooja

There are two different dimensions in my use of traditional Korean bedcovers: one is the formalistic aspect as a tableau and as a potential sculpture. The other is as a dimension of body and it's destiny that embraces my personal questions as well as social, cultural and political issues. The bright colourful bedcovers that celebrate newly married couples for happiness, love, fortune, many sons and long life are contradictory symbols for life in Korean society, for a country that is going through such a transitional period: from a traditional way of life to a modern one. -

Oliva María Rubio

Despite the fact that you say you are not political matters, you have created several installations or pictures that are clearly related to political or social events, such as "Bottari Truck in Exile" (1999), presented in the 48th Biennial exhibition of Venice, or "Epitaph" (2002), a photograph taken after the September 11th attack against the World Trade Center in New York. What are the reasons for you tackle these subjects? -

Kimsooja

My practices were started solely on my personal issues and structural questions on tableau, which can be seen in the beginning of my earlier 'sewing' work and my 'wrapping' series of Bottari. However, my artwork has gradually embraced basic human problems, which have recently become a bigger part of my questions and concerns. My own vulnerability and agony on life had a presence in my earlier work, which was an important part of the healing process for me to survive. It then transformed naturally into 'compassion' for others, and turned to the healing process for others. All of my works that relate to political issues and problems originate from 'compassion for the human being', people who suffer by violence, poverty, war and injustice, which often stem from individual problems and conflicts. I would say one can categorize some of my work as a political reaction, but it is more from concern on humanity, rather than as a direct political statement as an activist. -

Oliva María Rubio

Between 1999 and 2001 you created one of your most relevant video installations, "A Needle Woman". A product of performances where you are the protagonist, always in the middle of a crowd in Tokyo, Shanghai, New Deli, New York, Mexico, Cairo, Lagos and London. For the 51st Biennial exhibition of Venice (2005) you did a new version traveling to another six cities: Patan (Nepal), Havana, Rio de Janeiro, N'Djamena (Chad), Sana'a (Yemen) and Jerusalem. Taking into account that many of these countries undergo serious problems, have you ever felt that something could happen to you? Which has been the strongest experience you have lived through while you were doing these performances? -

Kimsooja

In terms of the performance itself, the A Needle Woman performance I did in Tokyo (1999) was the strongest experience I had. It was the first performance of the series. I was walking around the city with a camera crew to find the right moment and place where I could find the energy of my own body in it. When I arrived in the Shibuya area there were hundreds of thousand of people sweeping towards me, and I was totally overwhelmed and charged by the strong energy of the crowd. I couldn't help but to stop in the middle of the street amongst the heavy traffic of pedestrians. Being overwhelmed by the energy of the crowd, I focused on my body and stood still, and felt a strong connection to my own center. At the same time, I was aware of a distinguishable separation between the crowd and my body. It was a moment of 'Zen' when a thunderbolt hit my head, as I continued to stand still there, and I decided to film the performance with my back facing the camera. During the performance there were moments I was conscious of my presence, but with the passage of time, I was able to liberate myself from the tension between the crowd and my body. Furthermore, I felt such a peaceful, fulfilling, and enlightened moment, growing with white light, brightening over the waves of people walking towards me. -

Oliva María Rubio

The first series of "A Needle Woman" was focused on encountering people in eight Metropolises around the world. The second version, made in 2005 with the same title, was focused on cities in trouble, from poverty, political injustice, colonialism, religious and political conflict in between countries and within a country, civil war, and violence. -

Kimsooja

I chose the most difficult cities in the world, although I couldn't make it to a few of the cities I wished to visit, such as 'Darfur' in Sudan, and 'Kabul' in Afghanistan. It was one of the most difficult trips I've ever experienced in my life. The difficulties with this series of performances were more about the conditions of traveling, rather than during performance time. -

When I first visited Nepal, the country was in a state of emergency, and there was no phone service in between the cities and even countries, with no internet connection during most of my stay. Foreign ambassadors were being called back to their own countries, gunshots were heard from different parts of the country while traveling, and armed soldiers were occupying every corner of the streets in Kathmandu. Even in my video, there's a scene with armed soldiers passing by. To be able to travel to Havana in Cuba, I had to travel through Jamaica, as there was no direct airline service, and no collaboration whatsoever between the US and Cuba. In Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, I went to a huge favela area called Rocinha, where I heard a series of gun shots from one mountain side to another, as if they were shooting directly from the back of me. I was standing on the roof of the central part of the area surrounded by mountains of poverty although local people considered it to be signals between the drug dealers. I also saw a number of young men carrying guns in the middle of narrow alleys to control the people in that neighbourhood. I also witnessed more poverty in N'Djamena in Chad, which is known as one of the poorest countries in the world. I witnessed conflicts between Yemen and Israel. I could only travel from Sana'a in Yemen to Jerusalem via Jordan, as there's no direct airline service in between these two countries, and the Yemeni people wouldn't allow me to enter their country if I was traveling from Israel.

-

Oliva María Rubio

When you are in these types of situations, there is no room for fear. -

Kimsooja

People believe we live in an era of globalism, which allows us to travel freely and that we are connected to anywhere in the world, but in fact, it is not true, and the world is still full of discrimination, hatred, and conflict. -

When I finished these pieces, in slow motion, they turned out to be quite similar from one city to another, regardless of the problems within. We have a very shallow perception of ourselves in terms of our notion of time, and how we perceive an extreme situation in our own time frame, but in fact, all of these cities could be seen as a similar situation in a larger perception of time.

-

Oliva María Rubio

According to works such as "A Needle Woman" or even according to the symbolism of using the bottari, travel and changing places is very present in your career, both personal and professional. Could we say that the contemporary man is a nomadic being that is forced to go from one place to another without a rest? -

Kimsooja

Although the nomadic lifestyle is a characteristic phenomena of this era, it could also be one's choice. We can still live without moving around much and be rooted in one's own place. Human curiosity and the desire for communication expands its physical dimension and happen to control human relationships and the desire of possessions, and pursuing the establishment of a global community, which includes the virtual world. But a true nomadic life wouldn't need many possessions, or control, and it doesn't need to conquer any territory; it's rather an opposite way of living from a contemporary lifestyle, with the least amount of possessions, no fear of disconnection, and being free from the desire of establishment. It is a lifestyle that is a witness of nature and life, as a kind of a process of a pilgrim. Nomadism in contemporary society seems to be motivated from the restless desire of human beings and it's follies, rather than pursuing true meaning from nomadic life. -

Oliva María Rubio

During these past years you are going for site-specific projects. You have just finished one at La Fenice Theatre in Venice, and now this one in Madrid. What is the most attractive thing about this kind of projects? -

Kimsooja

I wouldn't say site specific installation projects are more intriguing for me than other projects such as video, performance, and photos, as these were also site specific projects from my point of view. The difference is, for this type of site-specific installation, there's a solid question already existing, which I am interested in pondering. But the answer may raise another question to the audience. Other projects, such as video, performance or photos, are those I am questioning from myself, my own problems either in art practice or life, and the questioning goes both ways, to myself and to the audiences. I am interested in problems, questioning, and responding to the conditions of the site. -

Oliva María Rubio

Once having seen the results of your project for the Palacio de Cristal (Crystal Palace) in the Retiro Park in Madrid, "To Breathe: A Mirror Woman", a work that consists of an intervention in the palace [a diffraction grating film that covers all the crystal part of the building and a mirror on the ground that works as the unifier and multiplier of the space and an audio with your own breathing from the performance "The Weaving Factory" (2004)], have your expectations been met? Is the result very different from your initial idea? -

Kimsooja

Not totally, but only in terms of some technical issues. I've never used the diffraction grating film in my work before, and I'd been experimenting with its effects on a small scale model. The effect coming from the Crystal Palace, with actual sunlight, and its degree and direction, created a much more spectacular environment than from the model. I could envision the effect of the mirror floor and the effect of the sound within the Palacio de Cristal, as I had already experimented with both mirror and sound in other installations. -

Oliva María Rubio

Considering that this new project for Crystal Palace is both a logical continuation and a new step in the development of your artistic career, what does it mean for you? -

Kimsooja

From this project, I discovered 'Breathing', not only as a means of 'sewing' the moment of 'Life' and 'Death', but 'Mirroring' as a 'Breathing self' that bounces and questions in and out of our reality. Evolving the concept from my earlier 'sewing practice' into another perspective, 'Breathing' and 'Mirroring' as a continuous dialogue to my work was the most interesting achievement of a new possibility in experimenting with waves of light, sound, and mirror as a result of the space of emptiness. -

Oliva María Rubio

What is the relationship between this installation and other previous needle and sewing works? -

Kimsooja

To Breathe: A Mirror Woman is related to my earlier practices such as 'sewing', 'wrapping', and the question of 'surface', as well as the notion of 'reflection', that was always a part of my work in the metaphysical sense. Interestingly, a mirror can be another tool of 'sewing' as an 'unfolded needle' to me, as a medium that connects the self and the other self. If 'mirroring' can be a form of 'sewing the self', which means questioning the self, and connecting the self, 'breathing' is, in its dimension of action, a similar activity of 'sewing' that questions our moment of 'Life' and 'Death'. In mirroring, our gaze serves as a sewing thread that bounces back and forth, going deeply into oneself and to the other self, re connecting ourselves to its reality and fantasy. A mirror is a fabric that is sewn by our gaze, breathing in and out. -

Oliva María Rubio

What is the relationship between "A Needle Woman" and "A Mirror Woman"? -

Kimsooja

Again this goes back to the idea of surface, a continual question. A needle / body, which questions and defines the depth of fabric / surface, and a mirror that embodies the depth of body and mind, defining our existence, through a needle. I am standing as a needle to show A Needle Woman video as a mirror of the world, to question my own identity amongst others. At the same time, I am standing as a mirror that reflects the world, gazing myself from the reflected reaction the audience bounces back to me. A needle is a hermaphroditic tool that can be a subject and an object, and this theory can be applied similarly to a mirror. In that sense, I can consider a 'needle' as a 'mirror', by definition and a psychological healing tool, and a 'mirror' as a multiple and unfolded needle woven with the gaze, as a field of questions. -

Oliva María Rubio

This intervention in the Palacio de Cristal is visually very beautiful but one may even feel some kind of anguish or have the feeling that he or she is in prison. How would you explain this effect? -

Kimsooja

People may feel as if they are in my body, as the Palacio de Cristal seems to breathe, or in a cathedral bathed with stained glass, or in a space of fantasy, while walking on a mirror floor that feels like a liquid surface. Hearing my breathing and humming within the space might cause the audience to hold its breath, and they may become conscious of their own body and breathing. Maybe this feeling of being imprisoned comes from the prison of ones' own body? -

Oliva María Rubio

Inside and outside, life and death, disruption and joy, anguish and delight, uncertainty and acknowledgement, these are aspects of feelings we feel when we are inside the Palace. Why are you interested in this idea of opposites, and duality? -

Kimsooja

From the beginning of my career, back in the late 70's when I was at college, I was already intrigued by the dualities existing in the structure of the world, that are the combination of 'Yin' and 'Yang' elements. I've been looking at all existing things and the structure of the world from this perspective. An example from my earliest sewn piece Portrait of Yourself, 1983, and also The Heaven and The Earth, 1994, have vertical and horizontal elements, or a cross shape. I've been establishing my structure of perception and creation through this perspective. There was a series of assemblage based on random shapes in my work from 1990, such as Toward the Mother Earth, 1990-91, and Mind and the World, 1991, where 'duality' as 'yin' and 'yang functioned as a hidden structure. On another level of the surface, there comes another layer of yin and yang relationships, and this phenomenon goes on and on in each dimension of structure. -

But this doesn't mean that I was doing art mathematically or logically most of my works were created by the most irrational decisions and a sudden intuition rather than building up theories or logic itself, and I have always believed in the logic of sensibility within the process of creation. Duality can be one way to start understanding existences of the world, although there are so many different factors that surround and define the structure of the world. When the creation process starts, this duality theory doesn't work anymore, and it goes beyond the logic, and leads it's own life and process.

-

Oliva María Rubio

Your works aspire to capture the whole of the human experience: the body and the soul, the mind and the body are appealed to in the same extent in your creations. Why is it so important for you to make art a nothingness that experience of the body and the senses, as well as of the mind and the imagination? -

Kimsooja

Ever since I was aware of the totality of the world, I had to work on it, and it naturally involved different aspects of ways of existences, structure of metaphysics, and that of frustration and fantasy. That's what I know, what we live, and what I can express. -

Oliva María Rubio

Throughout your career, we can see that your new pieces refer to other previous works. Each of your new installations has a trace, an element, something that relates it with previous works. Do you conceive the whole of your artistic career as a kind of 'work in progress'? -

Kimsooja

For me, there is no concept of a completion. I am just moving towards a future where I find a better answer than the previous answer. This is totally against commercialism, as the art market requires a finished object to be sold and to collect. My work is still evolving and unfinished, and is just a process. -

Oliva María Rubio

And in this sense, where are you heading to? What is your ambition as an artist? -

Kimsooja

If I have an ambition as an artist, it is to consume myself to the limit where I will be extinguished. From that moment, I won't need to be an artist anymore, but to be just a self-sufficient human being, or a nothingness that is free from desire.

─ This text was published in Art in Context, Summer 2006.

- Oliva María Rubio is an art historian, curator, and writer, who has been director of exhibitions at La Fábrica, since 2004. She was the Artistic Director of PHotoEspaña (PHE), an International Festival of Photography and Visual Arts celebrated in Madrid (2001-2003), where she programmed around 60 exhibitions. She is a member of numerous juries on art and photography, and a member of the Committee of Visual Arts “Culture 2000 programme”, European Commission, Culture, Audiovisual Policy and Sport, Brussels (2003), the Purchasing Committee at Fonds National d’Art Contemporain (FNAC), Paris 2004-2006, and artistic advisor of the Prix de Photography at Fondation HSBC pour la Photograhie, Paris, 2005. She was the curator of Kimsooja's To Breathe: A Mirror Woman at the Crystal Palace, organized by Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in 2006.

A Needle Woman, 2005, Patan (Nepal)

A Needle Woman, 2005, Patan (Nepal)

Kimsooja - A One-Word Name Is An Anarchist's Name

2006

-

Kimsooja (b. Taegu, Korea, 1957) is a world-renowned artist, who has been living in New York since 1999. She has been included in many important contemporary art publications throughout the world, and has been exhibiting her works in Asia, America and Europe. Her work includes installation, performance, video and photography. Nomadism has been a constant in her life since childhood, and has also become a strategy that she has been using continuously to articulate her artistic work — the imperatives of the ego, passion and desire; detachment from material, and relationships with other people, are a continuous search throughout her artistic creations. The main themes she deals with are movement, totality, time and space, life, death, and the ephemeral aspect of the material world. Different interpretations of her work offer a wide spectrum of readings and several contexts — from minimalism, feminism, nomadism, buddhism, to aesthetic and political ideologies. Nevertheless, the main purpose of her work is a mode of artistic creation, her belief in intuition, and reaching balance. Compassion is an element of Kimsooja's work that manifests also as a response, not in terms of direct political activism, but as conscience and conscious presence; as witness. Kimsooja's work was presented to Slovenia at the last year's exhibition The Fifth Gospel in Celje.

-

The following text is from a conversation with the artist Kimsooja, and the intense personal experience and subsequent reflection provoked by seeing her video works. The questions that followed the primary impulse was how did the artist, with seemingly minimalistic means, succeed in opening up a new perspective for the viewer, and at the same time awaken human consciousness in a remarkably simple and fascinating way. When we are standing in front of Kimsooja's artwork, we are actually confronting ourselves.

-

Petra Kapš

A One-Word Name Is An Anarchist's Name is the first statement on your website project. At first sight, the notion of anarchism seems to be in complete contrast with your work. On the other hand, your activities in the Western art world and society in terms of minimalism, detachment, reduction of the ego, your respect to nature and all living beings and unmindfulness of self-image, they all work subversively to that first impression. -

Kimsooja

What I made in this comment on my website, 'A One-Word Name Is An Anarchist's Name' was a symbolic cultural statement in respect to naming an individual who lives as an outsider from one's own society, as a spectator rather than as an activist who practices anarchism in an actual political context. -

Petra Kapš

In public you appear with the name Kimsooja, the identity of which is explained on your website with the following words: "A one word name refuses gender identity, marital status, socio-political or cultural and geographical identity by not separating the family name and the first name." Can your intentions in the art world also be indicated with these words? -

Kimsooja

I was actually more interested in the possibilities the art world has, which allows universal language and diversity. This is in contrast to my own limited socio-cultural daily life context from Korea — to be more independent as a human being out of hierarchy, to question and open up a new relationship to the society. -

The symbolic meaning of the different ways a married women's name appears in different societies is quite interesting — married women's names in Western society follow after their husband's name, and that of Asian women's follow after their own father's name, both of which eventually keep the male dominant family name. This gives an interesting contrast and level of perception of what degree and hierarchy those two societies are similar as male dominant societies, and different in terms of women's status. This idea of putting my first name and last name together suddenly stimulated my desire to be free from any of social structures, and expanded my imagination to obtain an absolute independency as a human being, within the art world at least. Different from a person's name in daily life, the name presented in the art world usually represents no personality or emphasis of their gender, but functions more as a symbol of a specific art practice as a character. However, it was a symbolic gesture for me to explain my social, cultural burden from Korean society, from which I wished so much to be liberated.

-

Petra Kapš

Upon entering your website, the user reads your words: "I was hoping for an ideal society and relationship among people in the art world in which we could share real opinions with honesty, sincerity, dignity and love of art and life. I hope that my website project will not just introduce my activities but can bring more articulated discussions and criticism on art and the world." The site was published on 14 July 2003 — what are your experiences with this appeal now? Also, what do the individual responses to your 'Action Two: It Is Not Fair' mean to you? -

Kimsooja

It is quite a delicate issue. Around the time when I decided to start my website, I was very disappointed by the dominate big international biennale scenes. Although I've been in many of these international events, and have had both positive and negative experiences, in general these international biennale scenes show very little respect for art and the artists. They seem to focus more and more on the power structure of the art world, and their specific political alliances with the artists and institutions, rather than the quality of the work or it's meaning. The peak of this phenomenon has past, and there seems to be an effort to make some balance between the role of artists and that of curators. There must be a balance between the creator and the organizer, and neither should empower the other, but instead communicate and encourage each other in equal amounts. Although both artists and curators have different attitudes and perspectives, in the end we always learn from each other. This is just one example of the varied relationships between people that I wished to address. -

The 'Action Two: It Is Not Fair' project was started to give an opportunity to question the notion of 'fairness' as it is related to this phenomenon in the art world, but rather than narrowing it only to the art world, I opened up a broader discussion. My position in this project functions as a 'witness' and as a 'questioner' rather than an answerer. All of the responses I've gotten gave me positive and negative questions and perceptions on the human relationship towards other humans, society, and to themselves. From the diverse and specific perspectives I've received, I have arrived at a fine balance of fairness on a broader level beyond the individual statements.

-

The fundamental creative principles, processes and concepts of Kimsooja's artistic articulation are continuously present since the beginning of her career. At first, she was mainly focusing on painting, specifically on questions about the surface. She created paintings out of pieces of fabric, combining sewing, painting and drawing. Her paintings were made of used fabric, rags, and clothing. The first clothing that she incorporated into her paintings were owned by her grandmother. She later started to collect used clothing from anonymous people, and to explore the their invisible presence in the fabric. From the early 1980's, sewing became the essential principle of her artistic process — sewing as a monotonous repetition of movement ... the possibility of a meditative gaze into the human interior (self) ... a fluid journey of mind and spirit. The processes of sewing, covering, and wrapping are tightly connected to everyday activities (mostly female activities in Korean, as well as in Western, tradition). Putting them into an artistic context creates a balance between the artistic procedures and the creative elements of everyday activities. The meditative process hidden beneath a common marginal act of sewing exposes the performative process of the reduction of the ego, already in these early works. With meditative means, the artist is reaching a certain state of consciousness, where she focuses and eradicates herself, and she simultaneously creates space for the viewers to enter. It can be present in the imprint of the body left on the used fabrics, the smell of anonymous people on clothing, and on bedcovers. This space is also 'the void' through which the viewer enters. By focusing on herself, she reaches towards the point where the ego slowly disappears. Kimsooja is creating the void, an empty space through which the viewer can reach the balance between human relationships and life.

-

With her residency in New York at the beginning of the 1990's, her experience based on living and working in Korea intermingled with that of a different view over her own artistic practice and cultural context in New York. Her artistic point of view was radically changing towards re-questioning cultural, social and political Korean traditions.

-

Petra Kapš

In talking about your work, we can use a few key words: journey (nomadism), detachment from matter or attachment to human being, existing beings, time, life, death, mobility as a necessary condition of life, totality. What is your relationship to these words? -

Kimsooja

I guess all these words are related to the destiny of our existence.I am questioning my own destiny in this world in various paths, but reaching to the totality of it. -

Petra Kapš

Your works express the relationship of life and art in a very special way. Is this the prime notion for your artistic engagement - art as a tool for understanding the mobility of life? In Martin Heidegger's conversation with Shinji Hisamatsu we find a very interesting word, geido — a 'path (journey) of art', this word comprises of a deeper relation to life, to our own being. It is a word for art that has substantial importance for existence. -

Kimsooja

I must say, the result of art making which we call 'art work' is a secondary thing for me. The most important part in making art for me is, "questioning life, self, the other, and the world", and finding my own path for answers, which leads to another question, as always. In that sense, I find geido, as mentioned by Shinji Hisamatsu, to be a very coherent interpretation. -

In the Korean tradition, it is quite common that bedcovers are received by newlyweds as a gift. The richly embroidered fabrics with symbolic patterns are filled with familial and social desires, expectations and demands. The bedcover is wrapped around the body in various life circumstances (among others, during birth, rest, sex, illness, death). In the eyes of a Western observer, this piece of fabric is an aesthetic object of provocative, intensely radiant colours. Colour is one of the most important constants in Kimsooja's work, contextually related to Korean tradition and Western modernism. The bedcovers that the artist includes in her work are discarded bedcovers, that have all served their time. The echos of a once present body remain as traces of smell and form.

-

By the beginning of the 1990's, Kimsooja used bedcovers as bottari (which means bundle), in which people wrap their belongings for travelling. She wrapped the clothes of anonymous people and daily objects within them. Bottari is a metaphor for the artist's life credo — a nomadism that is the basis of her creative practice. It implies the idea of a constant readiness to leave, detachment from the physical world, and is a universal metaphor for mobility. In the photo of the performance entitled Encounter, Looking Into Sewing, a figure is completely covered, with bedcovers draped over their head. This image brings several associations to the mind of the viewer — the image of a bride, a metaphor of torture. In this work, the artist has exposed strong feelings of intimate denial, abstinence (especially in the life of a woman from Korean society), and explored the relationship between the visible, and the hidden yet present. Bedcovers that imply an intimate environment are embraced in public spaces. The artist put them on café tables as table cloths in one of her projects entitled Deductive Object, presented at Manifesta 1 in 1996. By doing so she confronted an aesthetic exterior and functionality with the Korean prohibition of eating in bed.

-

In her project Sewing Into Walking - Dedicated To The Victims of Kwangju, 1995, Kimsooja piled up loose clothing, and clothing wrapped in bedcovers, and put them in a 2.5 ton heap. In the Korean tradition, clothing preserves the spirit of their owners, and are therefore burned after a person dies. In this installation, they represent the reincarnation of people, the memory and the guilt, over the massacre in Kwangju in 1980.

-

In the 11 day performance Cities On The Move - 2727 Kilometers Bottari Truck, 1997, she travelled through her childhood hometowns on a heap of bundles, bottaris loaded on a truck. In this way, her initial introspective sewing gaze manifested itself in a real journey. By later placing this truck in a gallery space (Bottari Truck In Exile, d'APERTutto, Venice, 1999) she transformed her personal experience into a universal issue of cycle and passing of life, and cohabitation of time and space. At the same time, by dedicating this installation to the victims of war in Kosovo, she took the position of a quiet yet indelible witness.

-

Petra Kapš

I am interested in your experience of suppression and endurance that you talk about in connection with the traditional Korean bedcovers. Bedcovers have a strong intimate seal for every individual. A bedcover can (un)cover the most intimate parts of an individual and the shape of life as well that is re-established by the cohabitation of two individuals. -

Kimsooja

It is interesting that you point out the word 'cohabitation' within the bedcover's hidden structure. Most people don't see that dimension, which involves another big issue in my life and work. People's gaze often ends up with the beauty of the fabrics or the cultural aspect of it, and imagining the couple's memory and intimacy, but there is another big issue in dealing with the 'reality of relationship' and 'self' and 'other' within this frame. Things become a question when they are problematic - it is good material to live and to question. Again this problematic 'co-habitation of duality' raises all sorts of questions on human existence. -

Petra Kapš

Time is connected with memory and reminiscence. One of the main topics you deal with is death. We can also understand your works as 'preservers of memory' of the dead, of the sufferers who are present in clothes, ashes, bedcovers, bottari, carpets, in cessation of breathing ... They are interventions against concealment and oblivion. Where does this continuous emphasis on life and death come from? -

Kimsooja

I am also curious about this continuity of my own concern: my obsession on body, death, and its memory to try to reveal the truth of victimized and disappeared beings, among other dimensions of my work. I think I have a strong compassion for all ephemeral beings, including myself. -

Aside from exploring various contexts of found objects and used fabrics, their meanings and physical presence, performance and video represent another area of Kimsooja's artistic activity. The series of video works A Needle Woman, 1999-2001 is a video record of performances carried out in eight world metropolises (London, Lagos, New York, Tokyo, Mexico City, Cairo, Delhi, Shanghai). The artist uses a consistent structure of visual imagery (a static camera frames the view, and the artist is turned away from the viewer, and is situated on the street with an extraordinarily large number of people). The artist's body is in a state of a seemingly static and deeply contemplative posture. The viewer meets the mass of moving people. The artist's body can be interpreted as the entrance door, a point of identification or watching (observing the relation of the passersby to the artist, we can only make conclusions about her responses to the people from their faces). If we focus on the pieces from Lagos and Tokyo, two extremely different realities, we can follow the whole spectrum of social, political and cultural contexts that we find in the response of people's bodies and faces. In the installation of these video works, we begin to observe particular specificities of people, small daily events recorded by the camera — unobtrusive presentation, emphasising the particularities of every individual. With her minimal intervention that is actually merely presence, the artist is documenting people in a simple way, positioning herself as observer, not an arbiter. The element of time modification causes variation in the recorded natural mobility of people and their surroundings. The minimal slowing down enables the viewer to observe details and characteristics in th continuous 'flow' of people, the image passing by remains conscious for a moment. The interpretative field of this series is extensive and applies to all Kimsooja's work. From the analogy of a sewing needle and the artist's body forming a relationship to the passersby with its immobility, exploring the responses on its presence for mental and physical personal space, to the social context of the heterogeneity of social phenomena and the role of human being in contemporary world.

-

One of the defining parameters of Kimsooja's work in this context is her research of movement, mobility. Her body seems to be immobile, completely static compared to the mass of moving people. This seemingly motionless body is also analogous with a statue, a static object.

-

Petra Kapš

The image of your body in video performances, being turned away from the viewer, addresses people in a special way. This body-image cannot be interpreted as a symbol, but as an emptiness that, on one side opens up the space for the viewer, and on the other represents mobility towards human life, to his essence. How do you comprehend your body at this particular point? -

Kimsooja

I find your perception of my body as a 'void' one of the most accurate and relevant descriptions of the presence of my body in my videos. The emptiness is created by turning my back towards the audiences, by not showing my personal identity, and also by allowing my body to function as a passageway for the audience to go through or enter into - this enables the audience to experience what I see and experience in situ. It is a similar function to a needle point, which has a decisive form of function, but works only through the empty hole of a needle eye, which is on the opposite side of the needle point. They can never meet each other, and they have this Yin and Yang relationship serving itself as a medium between fabrics. I weave the social and cultural fabrics with my presence and void as a medium. But I also believe that there's ego, which was not there while performing- I must say, standing there in the middle of the crowds was also a process of emptying my own ego, while receiving all of the people and their energy in my body and mind. This process of emptying the ego allows people to enter your body and create a void of your own self. -

Petra Kapš

Your artwork A Laundry Woman - Yamuna River, India, 2000 was shown at the exhibition The Fifth Gospel in Celje. The video projection was placed inside the Catholic Church of Saint Mary. The strong context in which the work was placed added an interesting analogy. Through the body of the artist - place/point of identification/entrance - the viewer entered into the artwork in the same way as Western civilization entered the body of Christ in history. How the viewer experienced it from this point onwards was dependent upon himself. The body functioned as a mediator. What are your thoughts about this different context that has a strong 'point of possibility' to influence the work? -

Kimsooja

Locating my body in the midst of crowds or in nature is to question my existence and that of others on what I see, where I am, and where we are going. It is the question raised from the experiences of these performances that leads me to go forward and question further. Relating my work within the context of the Catholic Church and its history can be controversial in the sense of my way of thinking and that of Catholicism. I am interested in this kind of contradiction, as it can sometimes create an unexpected innovation, as if two different ways of mathematics can solve the same question from a different method. When those two different approaches and energies crash and merge together, they can break through the existing way of thinking. This is a fascinating side of fusion in art making and art reading. -

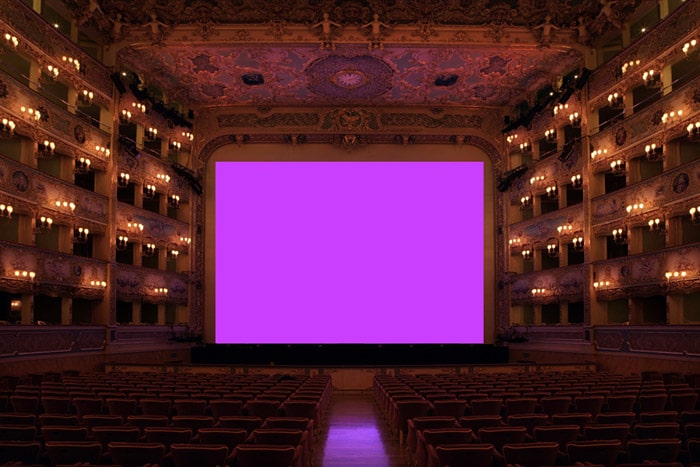

When the function of one sense is prevented, for whatever reason, other senses sharpen to compensate for the missing information. The artist uses this effect for achieving special (meditative) states in the viewer, and to sharpen the human senses that are necessary in perceiving reality. Her video works mostly exclude sound. The intensity of the video image overwhelms us in the beginning, and only gradually do we become conscious of the fact that individual sounds — the flowing of a river, the dripping of water, a gust of wind, birds singing, human speech, street noise — are all missing. With this absence (and consequently, the orientation of human consciousness toward a sole level of perception) the artist directs our attention to the field of the visible and further to the field of spirit. The sharpened act of seeing centers our perception exclusively on the image. There is an obvious intertwining of artistic and meditative strategies that mostly omit sound, and focus on directing the (inner) gaze. In her work The Weaving Factory, 5.1, sound is the only element of the installation. Simple and minimal expressive means are the logical choice for achieving the goal — to direct, to sharpen the sight, and hearing. This year, the artist joined light, colour and sound in her work To Breath / Respirare, presented in La Fenice theater in Venice. The video installation was a combination of the projection of intensive monochromatic colours alternating in regular rhythm and the recorded sound of the artist's breathing. The sound element transitioned from a relaxed tempo that aroused pleasant, relaxed feelings, to an unbearably quick tempo, awakening anxious feelings verging on physical pain.

-

Petra Kapš

I have experienced your art works as a visual world, and a world of silence, where different phenomena are shown that lead the viewe into (self) consciousness. Furthermore, this consciousness of things that are outside of us aims at harmonizing and balancing the individual in life. -

Kimsooja

A sense of consciousness, equilibrium and harmony has played an important role in my work, but at the same time, this is nothing but my own personality. I used to raise questions from the point where the consciousness of an unbalanced and un-harmonized situation stays — that which has a lack of care or lack of fulfillment as a whole and as a oneness. The whole process of making art is about balancing the situation through a Yin and Yang perspective, like an acupuncturist. I often see the situation in the complexity of duality and try to find the necessary remedy for it. -

Petra Kapš

On watching your video works (in Celje and Venice) I had a very interesting experience of time; with each work I had a feeling of being thrown out of the common concepts of time. Time extended, or it was as though it did not exist anymore. How do you define time? -

Kimsooja

I often feel that I am in a state where I am out of a specific time frame, either in the midst of concentration or in a meditative state. When I see my videos, I feel similar states of my own experiences I have in daily life. Time is not there when I am there, and when there is time I am not there anymore. Time exists when one has consciousness of the other or one's other self - when one can see the other, even oneself as the other. Time is the body that you see with your eyes of consciousness. Time exists when a separation of your body and consciousness occurs. Time is space, and space is time. -

Petra Kapš

What are your feelings about your past projects? -

Kimsooja

All of my past work functions as just one 'station' towards another, as a process to reach to the final destination towards 'void', or the 'extinguishment' of my artistic and existential self. -

Petra Kapš

What role does beauty play in your life and aesthetics? What is your relationship to this phenomenon? -

Kimsooja

I believe in beauty as a reflection of truthfulness, harmony, and purity — but also as a reflection of decadence, as well as in its inevitable complexity within its own contradiction. Beauty is discovered when the viewer has eyes for it, and everything in this world has its own connection to beauty. -

Petra Kapš

Ethics, which has played an important role in the history of Western art, was not discussed in connection with art in the time of modernism. This situation is changing at the moment. Your works express strong ethical messages. What is your attitude towards these two spheres of ethics and contemporary art? -

Kimsooja

Ethical attitude generally comes from the pursuit of harmony and concern of others. I think art can be ethical in the pursuit of beauty and reality, although there's some contradiction between art and ethics in aesthetic methodology. Art often didn't respond much to the reality of our life and present time in modernism, and the creative process of art making often involved a de-constructive element. There are also so many different levels of ethics - ethics for ethics, ethics to prove truth and fairness, ethics that revenges the negative phenomena of society. These two aspects of being destructive in their own process and being ethical to idealism can be coherent at some level and it is inevitable to respond to present conditions of life in any form. -

Petra Kapš

It seems that nowadays we consume art only through filters of digital technology, images in a digital camera or a movie camera. Watching through digital media is like consumption, I watch with my eyes like I use things; a commodity. But at the same time, it seems that these media membranes do not mutilate your work. The viewer doesn't need any knowledge of contemporary art for experiencing your work. Are such effects important for you? -

Kimsooja

I don't think much about the viewer's point of view, or have interest in guiding them to a particular way of looking at my work. What leads the viewer to access my work is probably because I am not dealing with only specific issues and questions in contemporary art, but also with essential questions on life from mundane daily life. -

Petra Kapš

How do you develop your works from the first impulse to the final realization? -

Kimsooja

In most cases, the first impulse leads to another reflection that creates a concept, and the concept leads to another impulse and they fuse ... But sometimes just one intuition or concept is enough. -

Petra Kapš

It seems as though Korean tradition is getting more and more hidden, covered in your work. -

Kimsooja

I left Korea at the end of 1998 after participating in the Sao Paulo Biennale, and I've been living in New York since then. As the years go by, my living and working conditions are more based in New York daily life and my travels throughout the world. I live in a somewhat different social and cultural life than in Korea, although I still question Korean culture and my own identity and relationships. I've started working with daily objects I discover in New York, communicating and thinking more in English, and being aware of the political and socio-cultural status of my present living conditions within the world. -

I consider myself to be a cosmopolitan, which might be the reason why the Korean cultural elements I used to deal with have been disappearing little by little from my work. But I am sure, at some point, there will be another moment when I re-discover my own culture from a different perspective than when I was in Korea.

-

Petra Kapš

You have been working in the Western world for almost a decade now. What is your relationship to the Korean period today? What did the last decade give to you? -

Kimsooja

It gave me personal independence, financial support, social freedom, and detachment from my society and relationships. -

Petra Kapš

What would you say about the notion that your art works are not questioning particularity of subjectivity that is so relevant today but are addressing fundamental questions of being, basic questions of life such as the balance of inside and outside, spirit and body, mind and soul, human as a natural and cultural being, being that exists in time and space of 'now'? -

Kimsooja

I have always been dealing with present issues around me and the society that I was in. People sometimes see it that way because I used traditional materials, but it was my and my society's reality, although diminishing, and it had symbolic cultural connotations that are part of contemporary global society's issues as well. I just didn't use Western fabrics or images as it wasn't my reality and they created strong present questions for me. If I used Western fabrics, I wouldn't have been able to create my own conceptual context as a relationship to the bedcover, body and cohabitation — that has to do with my reality within Korean culture. -

Petra Kapš

Are there any new horizons in your art? -

Kimsooja

I know my work goes further and further away from the materialistic world but I am still interested in materiality itself as a strong presence of existence and a body of time. I also know that the whole process is just an endless circulation of comprehension of the world and self, and I wish one day I could be just a simple being freed from desire of making art and see as it is and live as I am within the world as it is.

─ Likove Besede, Summer 2006, pp.75-76.

-

- Petra Kapš is an independent curator, art critic and writer. She is MA candidate at the Department of Philosophy at the University in Maribor, Slovenia.

A Needle Woman, Sana' (Yemen), 2005.

A Needle Woman, Sana' (Yemen), 2005.

An Interview with Kimsooja

2006

-

Kimsooja came to international fame in the 1990's following a P.S.1 residency in New York, which paved the way for one of her most famous pieces to date, Bottari Truck, a video that was subsequently shown in numerous exhibitions and biennales. Bottari Truck consisted of a truck loaded with bottari, the Korean word for bundle, and traveled throughout Korea for 11 days. The bundles were actually made of bed covers, an item accompanying the key moments of our existence from birth, marriage, sickness, to death. A Needle Woman, a video performance showing the artist from the back standing in the middle of a mainstream avenue in various cities throughout the world, further developed the concept of sewing towards abstraction bringing together people, cultures and civilizations. In a subtle way Kimsooja (b. 1957 in Korea), who works primarily in video, performance, installation, and photography has advanced to a premier artist in her discipline taking up sensitive issues like migration, integration or poverty. Besides taking us on her journey, Kimsooja's work is an invitation to question our existence, and the major challenges we are facing. In the interview below, she looks back at the past decade, and discusses her latest projects and undertakings. Olivia Sand reports.

-

Olivia Sand

Certain pieces you completed are seminal pieces (see above), and have toured numerous biennales and museums over past years. What mikes these pieces so important and why do you think people feel attracted to them? -

Kimsooja

The formal and the aesthetic aspects may draw people to these pieces, but I believe their success is also based on their content and the topics they address. Today, it seems that we are witnessing a 'cultural war' with many, issues arising in a global context bringing together different races and beliefs with an increasing discrepancy between rich and poor, economically powerful and less powerful countries. Needless to say, the present power structure causes many problems and disasters around the world. The issues that I address in Bottari Truck and A Needle Woman are very much related to current topics, such as migration, refugees, war, cultural conflict, and different identities. I think people are interested in considering these topics through the reality of the work; this may be one reason for their success. In addition, the aesthetics and some elements of the form in A Needle Woman, for example, are things with which people can identify. The piece demonstrates a different approach towards performance compared to what has been done in performance so far. It is a different format and a different perspective from a 'classical' performance, where the artist is 'doing' an action. I believe that you can connect people and bring them together to question our condition without aggressive actions. -

Olivia Sand

You learnt to sew with your family. Is sewing actually the element that led you to pursue an artistic career, ultimately serving as a means of expression, which remains to this day in your work? -

Kimsooja

Definitely. The practice and my concept of sewing represent the constant basis of all of my work, from the beginning until today. The concept of sewing is always redefined, redeveloped and regenerated in different forms. After sewing pieces on the wall, or the Bottari pieces, which represent another way of three-dimensional sewing, I began to connect the relationship between people, my body, and another way — actually an invisible way — of sewing, like weaving the fabric of society and culture for example. My practice of sewing is always evolving, generating new ideas to redefine concepts. -

Olivia Sand

You recently started a website, www.kimsooja.com. While presenting the site, you come to the conclusion that 'a one word name is an anarchist's name'. What do you mean by that? -

Kimsooja

I do not think of myself as an anarchist with any critical political meaning. I see myself as a completely independent person, independent from any belief, country, or religious background. I want to stand as a free individual, who is open to the world. -

I had thought about starting a website for some time, but I was reluctant to do so because of the commercial aspect linked to such an undertaking. One day, however, I decided to move forward, and I began to carefully think about a website address. With the rapid growth of the internet, an email address is the key to getting access to the world to a universe without boundaries. I wanted to present myself as a free individual from any connotations (which exist around a name — the affiliation through marriage, for example), but not as an aggressive anarchist activist trying to change the world.

-

Olivia Sand

On your website you talk about 'twisted information', and your desire to promote ideas that have not been given the importance they deserve. To what are you referring? -

Kimsooja

I realize that the media cannot be objective towards all the topics they cover, and personal points of view and experiences are also of great importance in the way the news is presented. However, I frequently witnessed how the media failed to acknowledge the relevance of an artist, which also resulted in ignoring or misunderstanding some of their existing art works. Through the website, which I launched in 2003, my goal was to open a forum for people to communicate openly and honestly about the art world, and the world in general. I am aware that it is a very modest undertaking, but I nevertheless wanted to offer a place where people could share their thoughts. All too often, people find themselves in a situation where they have no power, where they are manipulated, and they have no means to access or reveal the truth. So far, there have not been many people from the curatorial side, but there are many ordinary people, and a few artists, who use the site. -

Olivia Sand

It seems that people are used to getting distorted information... -

Kimsooja

In a certain way, yes. I think this can mainly be attributed to the fact that whatever is written becomes true, and people tend to believe whatever is written. I just want to provide a forum for people who want to speak up. -

Olivia Sand

It seems that we are living in a strange time: never has the access to information been so great and the sources so diverse, but a lot of people just seem to be getting and relying in 'distorted' information. Do you agree? -

Kimsooja

We just need to consider our domestic television networks (in the US), which provide very little information on foreign countries, on their view and response regarding the status of America in the world today. One needs to rely on the European and Asian channels to get a better awareness of what is going on in the world. As an artist, there is always a dilemma: should an artist take action following certain political decisions or should an artist stay away from politics? In my case, I want to open the floor for people to discuss and exchange ideas. In a way, I am a witness and I am not making any direct comments or statements. I do not see my role as to judge people, but rather as to raise awareness about certain topics. The response will be in the hands of each individual. -

Olivia Sand

Do you feel that today artist have the power to set things in motion? -

Kimsooja

Yes and no. Yes, artists could set things in motion, and can be very 'loud', but artists do not have enough power to persuade people to change the world. However, we are responsible for our own example and how we perform them. It is not necessary to make political statements, for example, but we can make a statement in a beautiful, peaceful, and spiritual way. In my opinion, artists can do something to resolve certain problems, but it is not easy, and it tends to remain a modest attempt of a very different scale than the head of a political section. Within a few seconds, they can give instructions to empower certain people, yet take it away from others. As modest as our attempt may he, I think it is important to bring attention to the suffering and death caused by unconditional unfairness. We cannot just neglect that. -

Olivia Sand

Nam June Paik passed away at the beginning of this year. Do you feel that in terms of contemporary art, he has left a legacy behind in Korea? -

Kimsooja

Absolutely. Before the 1988 Olympic Games in Seoul, he had no presence in Korea, nobody knew him except for some art insiders, and none of his works were shown. Although since 1988 things have changed dramatically, and Nam June Paik has been widely seen in Korea, still I do not think he received enough recognition or support from the Korean government. Throughout his career, he did a lot for Korea, and for the Korean people. He was very influential on Korean artists, and he contributed to creating a good image of Korea. He should have been more appreciated and supported by Korea, the Korean people, and by Korean museums. However, I am glad that ultimately the county where Nam June Paik was born has decided to build a museum dedicated to his work. The county has been acquiring hundreds of his pieces, and I consider it a great gesture — all the more so as it is based on the initiative of a provincial political officer and not a museum. This is very encouraging, as the museum will permanently be dedicated to Nam June Paik. -

Olivia Sand

Has Nam June Paik changed the attitude of museums in Korea, encouraging them to collect the work of contemporary Korean artist like you, who are mainly working in video and performance? -

Kimsooja

Presently, only one of my pieces is in a Korean museum: A Needle Woman, which belongs to the Samsung Museum. This specific piece caused many difficulties when the museum decided to acquire it, as my video piece was purchased by the museum, the Korean government charged considerable tax on it because it was considered a commercial movie. Consequently, the Samsung Museum and the Korean tax customs were in a lawsuit for many years. Korean law makes no differentiation between contemporary art works like my video pieces and a mass production commercial movie. Ironically, the tax authorities believed my video work was similar to Nam June Paik's work, which is considered the father of video art. The museum finally won the lawsuit last year, but it took over five years to settle the dispute. My case set a precedent, and today, artists can sell their video pieces without paying these enormous taxes. So far, A Needle Woman remains the only piece from my work in a museum collection in Korea. -

Olivia Sand

What is the reason for your 'under representation' in museum collections in Korea? -

Kimsooja

It is difficult to say. Perhaps it has a lot to do with the way the system (the galleries, the museums etc.) work, or perhaps they simply do not like my work. -

Olivia Sand

Is your work widely represented in American museums? -

Kimsooja

My work is represented in some American museums (P.S.1, some West Coast museums, etc.), but most of my projects are actually taking place in Europe. -

Olivia Sand

Do you think your work is 'too different' for an American audience? -

Kimsooja

I think the perception on art is very different in America and in Europe. If we take a closer look at the gallery scene in New York, most of the shows taking place in Chelsea are based on 'products' and people buy these 'products' rather than artworks that inspire them. I think the materialistic perception and the environment in the US clearly influence the collectors and their taste. There are always some exceptions, but I personally tend to find European audiences more sensitive, often more knowledgeable, and perceptive. -

Olivia Sand

You presently have a show in Madrid that runs until July. Can you describe the piece? -

Kimsooja

The exhibition is at the Crystal Palace, which is run by Reina Sofía. It is a beautiful glass pavilion, and I decided to create one large single installation. I covered the whole glass pavilion with a diffraction grid film, which creates a rainbow like effect all over the surface. The effect varies quite dramatically over the glass depending on the light source, the direction of the light, and its sharpness. In addition, there is a mirror structure over the floor, which reflects the entire structure of the building below the feet of the audience. I also installed the Weaving Factory, which I previously showed in Venice. -

Olivia Sand

How would you say your work has evolved since your residency at P.S.1 in New York? -

Kimsooja

For me, P.S.1 was one of the most influential experiences: it opened my career to the international art world. It led me to create my Bottari piece, and I started to do more installations based on my work from P.S.1. When I went back after a stay abroad, I became aware of the cultural conflicts within Korean society because by that time, I had the experience that things could be different. I had even more difficulties after coming back following a one year and a half stay in New York. I had to struggle because I had different perspectives, while the society was still very closed, stressful, and not supportive. I decided to leave the country to settle in New York, which was difficult, but at the same time very challenging. Putting myself on the edge of my life was a great challenge, and in retrospect, I think it made my professional practice even more focused, and more in depth. Since then, everything has been positive with museum shows around the world, participation in the most prestigious international shows and biennales, and good reviews. -

Olivia Sand

Has religion, Buddhism, had an impact on your projects? -

Kimsooja

I am not a practicing Buddhist, but I am very interested in Buddhism. It is very similar to the way I am thinking and to the way I perceive life, death, and daily life. I believe it carries great truth, but I do not want to represent any specific religious belief. I want to go beyond that, and embrace everyone's beliefs. -

Olivia Sand

Which projects are closest to your heart? -

Kimsooja

The sewing piece, the Bottari piece, and, of course, A Needle Woman. The Lighthouse Woman was also one of my favorite projects, in part because it was temporary and site specific with a very special environment and collaboration. I am strongly drawn to the idea of completing additional site specific and temporary installations, especially in Europe, where there are numerous very interesting sites.

─ This text was published in Asian Art Newspaper, May 2006.

-

- Olivia Sand is a correspondent for the Asian Art Newspaper based in New York, and Strasbourg, France. She contributes to The Asian Art Newspaper on a monthly basis, covering the Asian contemporary art scene. The newspaper, published out of London, serves as a thorough information source on the world of Asian art.

김수자: 레스 이즈 모어(Less is More)

2006

-

김수자(1957년 대구 출생)는 오랫동안 진지하게 작가 인생을 이어오며 설치, 퍼포먼스, 사진, 비디오, 장소특정적 프로젝트 등을 통해 자신만의 세계관을 발전시키는 데 전념해왔다. 확연하게 드러나는 그의 특이성에 동양의 특정한 철학이나 예술 전통을 연관 지으려 한 이들도 있었지만, 그가 다루는 핵심 소재는 현실 자체이다. 그의 작업을 특징짓는 개념은 그가 삶과 예술, 개인으로서 존재와 우리와 타인의 관계, 비어 있음과 존재의 덧없음에 관해 던진 질문에서 비롯된다. 그의 성장 과정과 살아온 경험은 기독교와 서구 철학이 선불교, 유교, 샤머니즘, 도교와 긴밀히 얽혀 독특하게 융합하는 사유가 형성된 배경이 되었다. 서양 미술사에서 그의 작업과 비견할 대상을 퍼포먼스와 신체예술 쪽에서 찾아볼 수 있는데, 마리나 아브라모비치, 울라이, 발리 엑스포트 등이 김수자와 유사한 문제의식을 보여준다. 하지만 그는 동양이든 서양이든 어떤 이론이나 철학에 휩쓸리는 대신에, 자기 삶의 이야기와 기억과 감수성에서 출발해 사회적, 정치적 현실을 파고드는 궤적을 밟아왔다. 김수자의 작업은 보편성에 깊이 뿌리를 두었고, 인간 경험의 총체성을 포착하려 한다. 그의 작품은 마음과 신체와 영혼 모두에 주목한다.

-

바느질한 오브제를 드로잉과 회화에 결합하는 추상 콜라주 작업을 해오던 김수자는 90년대에 들어서면서부터 <연역적 오브제(Deductive Objects)>라는 이름의 설치작품과 공간 오브제를 만들기 시작했는데, 여기에서 오브제를 감는 행위는 그 자체로 은유적 바느질 행위였다. 그리고 바늘, 천, 실, 조각보 등이 그의 창조적 우주를 이루는 일부가 되었다. 꿰매기, 감싸기, 접기, 펼치기, 덮기는 그가 거듭 되돌아가는 행위이다. 그가 택한 재료와 방법은 한국에서 천을 다루는 전통 방식에서 유래한 것이다. 1993년 김수자는 뉴욕에서 열린 두 개의 전시에서 보따리를 처음 등장시켰다. 레지던시 프로그램 참여로 1년 앞서 도착해 머물렀던 PS.1에서 열린 전시와, ISE 재단에서 열린 전시였다. 보따리는 천이나 옷가지 등을 낡은 한국식 전통 이불보로 감싸 묶은 꾸러미이다. 작가의 설명대로, 누군가 쓰던 이불보에는 "냄새, 기억, 욕망까지도 담겨 있어, 사용했던 사람의 정신과 삶이 묻어 있다." 그때부터 한국 문화에서는 이 평범한 물건, 보따리는 김수자의 작업에서 상수와 같은 존재가 되었다. 한국에서 보따리는 이동(자발적이든 강제적이든)과 연관되는데, 옷이나 책, 음식, 선물 등 깨질 염려가 없는 가재도구를 나르는 데 쓰이기 때문이다. 김수자는 가능한 온갖 조합으로 보따리를 선보였다. 보따리만 개별적으로 보여주거나, 바닥에 펼친 이불보와 나란히 놓기도 하고, 풍경을 배경으로 두어 물건 운반이라는 본래의 기능을 상기시키며 유목민적 가치를 상징하는가 하면, 비디오 설치와 병치하기도 한다.

-

2000년과 2001년 여러 나라를 방문하여 비디오 연작을 제작한 그는 <보따리>를 반복하여 제목으로 삼았다. 그중 하나인 <보따리 – 조칼로(Bottari–Zócalo)>는 멕시코시티의 조칼로 광장을 가득 메운 거대한 인파—사람들 역시 색색의 작은 보따리와 같다—를 비디오 보따리로 보여준다. 또 다른 작품 <보따리 – 알파 해변(Bottari – Alfa Beach)>은 나이지리아의 옛 노예무역항에서 찍은 작품으로, 위아래로 이분할된 화면에 바다와 하늘이 뒤집혀 있다. 쉼 없이 앞뒤로 파도가 드나드는 녹회색 빛 바다에 이따금 파도가 부서지며 하얀 포말이 인다. 이 바다의 움직임은 바로 아래 화면 속 뭉게구름이 뜬 고요한 하늘과 대조를 이룬다. 작품은 눈앞에 드리운 알 수 없는 미래에 노예들이 느꼈을 불확실성을 전한다. <보따리 – 눈 그리기( Bottari – Drawing the Snow)> 에서는 백색의 스크린 위로 검은 눈송이가 흩날리며 떨어지는데, 무리 짓던 새들이 사방으로 흩어져 날아가는 듯하다. <보따리 – 일출을 기다리며(Bottari – Waiting for the Sunrise)>는 멕시코의 레알 데 카토르세에서 촬영한 작품으로, 고정된 카메라가 지평선까지 이어지는 자갈길을 바라보고 있다. 낡이 밝아오지만, 아직 해를 볼 수는 없다. 화면에 아무 움직임 없이 5분 가까이 지나는 동안, 우리는 시간의 느릿한 움직임을 느끼며 풍경을 분간하려 애쓴다. 그러다 저 멀리서 하얀 불빛이 화면 오른쪽에서 왼쪽으로 다가오고 있음을 알아챈다. 빛이 길 한가운데 자리하는 순간, 마치 시간과 공간이 결합한 듯하다. 하지만 불빛이 우리 정면으로 향하기도 전에, 비디오는 끝이 난다.

-

다른 네 편의 작품과 함께 2006년 1월 베니스의 베빌라쿠아 라 마사 재단에서 열린 전시에서 처음 공개된 이 세 편의 비디오는 김수자의 최근작들을 예견하는 전조와 같았다. 이 작품들은 소리가 없는 작품이다. 마치 우리가 공간 자체에, 화면에 집중하기를 바라기라도 하듯, 작가는 시각에 유독 중요성을 부여한다. 나머지는 모두 관객의 상상에 맡겨져 있다. 그의 비디오 작업에는 움직임, 여행, 이행, 방향상실, 불확실성, 희망 등 우리 삶에서 중요한 역할을 하는 요소들에 대한 감각이 항상 깃들어 있고, 그래서 이 세 작품은 김수자의 이전과 이후의 작업 모두와 연결된다. 김수자는 유사성과 은유가 특별한 타당성을 얻는 삶의 여러 측면을 고찰한다.

-

보따리 외에도, 김수자의 작업에 특징적으로 나타나는 또 다른 요소는 누군가 오래 쓴 색색의 한국 전통 이불보이다. 그에게 이불보는 성, 사랑, 몸, 휴식, 잠, 사생활, 다산, 장수, 건강을 상징하는데, 요람에서 무덤까지 인간 삶에 늘상 존재하는 의미 깊은 요소들이다. 보따리와 비슷하게 이불보도 여러 작품에 다양한 방식으로 등장한다. <바느질하며 걷기(Sewing into Walking)>(1995)에서는 바닥에 펼쳐져 있고, <연역적 오브제>(1996)에서는 보따리와 짝을 이루었으며, <만남 – 바라보며 바느질하기(Encounter – Looking into Sewing)>(1998-2002)라는 제목의 사진에서는 마네킹을 이불보로 덮어, 정체성의 상실과 타자와의 관계를 이야기했으며, <빨래하는 여인(A Laundry Woman)>(2000)과 <거울여인(A Mirror Woman)>(2002) 같은 작품에서는 빨래터를 연상하는 설치 작업을 하였는데, 이는 여성의 역할에 대한 또 다른 메타포이다. 이 두 작품은 리옹 현대미술관과 뉴욕 피터 블룸 갤러리를 포함해 여러 곳에서 전시된 바 있다.

-

90년대 중반부터, 김수자는 기본적으로 일상을 기록하고 녹화하는 과정 속에서 본인의 몸을 매개로 한 개념적 퍼포먼스로의 전환이 이루어졌다. 1997년부터 2001년 사이, 그는 세계 곳곳의 여러 도시와 장소에서 행한 퍼포먼스를 담은 비디오 연작을 제작했다. 그러한 과정과 결과물 모두 우리와 타자의 자아 사이에 내재한 긴장을 화해시키려 한 그의 시도와 연관이 있다. 첫 번째 비디오의 제목은 <바느질하며 걷기– 경주(Sewing Into Walking – Kyungju)>(1994)이다. 이후 <떠도는 도시들 – 2727km 보따리 트럭(Cities on the Move – 2727km Bottari Truck)>은 1997년 11월 제작된 작품으로, 색색의 보따리들을 실은 트럭을 타고 한국을 떠도는 11일 간의 여정을 담았다. 7분 3초 분량의 영상은 시공간의 여정을 기록한다. 끊임없이 경계를 넘는 작가 자신의 삶에 대한 은유이자 현대 미술가와 우리 사회 전반의 한 특징을 나타내는 것이기도 한다. 노마디즘은 김수자의 예술에서 주축을 이루는 요소 중 하나로, 보따리를 상징으로 삼은 설치나 다른 비디오 등에서도 확인할 수 있다.

-

이 비디오 연작의 공통분모는 여성의 형상으로, 카메라를 등진 채 미동도 하지 않는 여인, 즉 김수자가 등장한다. 이 여인은 수많은 배경 속에 등장한다. <바늘여인(A Needle Woman)>(1999-2001)에서는 도쿄, 상하이, 뉴델리, 뉴욕, 멕시코, 카이로, 라고스, 런던의 행인들 사이에 서 있거나 일본 기타큐슈의 바위에 누워 있다. <구걸하는 여인(A Beggar Woman)>(2000-2001)에서는 카이로, 멕시코, 라고스의 인도에 앉아 동냥을 하고, <집 없는 여인(A Homeless Woman)>(2001)에서는 뉴델리와 카이로의 길거리에 누워 있으며, <빨래하는 여인( A Laundry Woman)>(2000)에서는 뉴델리의 강가에 선 모습이다. 하지만 그곳이 어디든 작가의 형상은 언제나 다가갈 수 없는 존재로, 관객에게 얼굴을 보이지 않는다. 그렇기에 군중에게는 허락된 것이 관객에게는 허락되지 않는다. 우리에게 얼굴을 보여주지 않고, 우리 자신에 관해 스스로 불편한 질문을 던지게 만드는 그 여인은 추상이 된다. 야무나강 앞에 서서 부동하는 여인의 이미지는 강물과 합쳐져 물결에 떠내려가는 잔해와 함께 멀리 흘러가버린다. 이들 작품에서 부동성은 모든 것을 감싼다. 하지만 작가는 단호히 화면 중앙에 자기를 세우면서도, 그로부터 자신을 거리두기 하는 데 성공한다. 작품 속 단출하면서도 묘하게 기운찬 작가의 모습은 일종의 자기확언이다. 김수자는 한편으로 자기 자신이자 동시에 '타인'이 되며, 존재하면서 동시에 부재하는 일을 해낸다. 그는 우리가 던지는 시선의 주체이자 객체이며, 개인이자 추상이고, 특정 여성이자 모든 여성이며, 도구이자 배우이며, 부동하면서도 단호하다. 이처럼 매끄럽게 이어지는 이원성은 2001년 쿤스트할레 베른에서 열린 《김수자, 바늘여인(Kimsooja, A Needle Woman)》전시 도록에 수록된 「자명하지만 문제를 제기하는(Obvious but Problematic)」이라는 글에서 베르나르 피비셰가 설명했던 것이다.

-

작가가 선 분주한 거리의 풍경에도 소리가 없기에, 작품 감상은 순수 시각의 차원으로 환원된다. 누가 저 여인을 촬영하는 것인지, 여인은 어떤 사람인지, 군중을 마주한 여인은 어떤 표정을 지을지 우리는 알지 못한다. 거리를 지나는 거대 도시의 주민들은 뜻하지 않게 배우가 된다. <바늘여인> 비디오에서 작가는 사람들로 넘쳐나는 길거리 한복판에 가만히 서 있다. 그의 절대적 부동성은 대도시의 떠들썩함과 대비되고, 우리 귀에 들리지는 않아도 분명 존재할 소음과도 대조를 이룬다. 카메라는 도시의 거리에서 발걸음을 옮기는 군중을 화면에 담는다. 카메라는 익명의 군중 얼굴은 보여주지만, 작가의 얼굴은 숨긴다. 행인 수천 명이 여인을 향해 걸어와 카메라의 시야에 들어섰다 사라진다. 카메라는 마치 사회학자처럼 '타자'를 대면한 군중의 반응을 기록한다. 런던, 뉴욕, 멕시코 사람들은 대부분 여인을 지나며 못 본 체한다. 상하이, 뉴델리, 카이로에서 여인은 좀 더 큰 관심을 일으킨다. 어떤 이들은 뒤돌아보거나 잠시 멈춰 그를 바라보기까지 한다. 하지만 가장 큰 호기심을 자아낸 곳은 라고스로, 비디오는 한 사람 한 사람의 얼굴과 감정과 반응을 보여준다... 하지만 도쿄의 경우 익명의 군중에 드러난 감정의 요소라고는 어느 여성의 얼굴에 떠오른 미소가 유일하다. <집 없는 여성>에서는 카이로 사람들이 가장 큰 관심을 보인다. 일군의 남성들이 못 이기고 여인에게 접근해 가까이 다가와서는 카메라를 똑바로 바라본다.

-

2005년에 열린 제51회 베니스 비엔날레를 위해 김수자는 파탄(네팔), 하바나, 리우데자네이루, 은자메나(차드), 사나(예멘), 예루살렘 등 도시 여섯 곳을 더 방문해 <바늘 여인>의 슬로우 모드로 된 새 판본을 만들었다. 연속된 여섯 개의 스크린이 하나의 비디오 설치로서 절대적 침묵 속에 전시된 가운데, 우리는 와글대는 행인들 소리와 멀리 도로의 소음을 그저 직관으로 느낄 뿐이다. 다시 한 번 작가는 우리로 하여금 자신이 빚은 그 형언할 수 없는 인물을 두고 사람들이 보이는 다양한 반응을 마주하게 한다. 새롭게 추가된 비디오 중 사람들이 작가의 존재에 가장 궁금해하는 곳은 리우데자네이루이다. 예루살렘에서는 몇몇 사람만이 호기심 있게 바라보지만, 경찰관 한 명이 미소를 지으며 작가에게 다가와 쳐다보고는 구경꾼들을 손짓으로 물려 보내고 그를 혼자 있게 해준다. 하지만 전반적으로 보아 행인들은 작가보다는 그의 오른쪽에서 벌어지고 있는 어떤 일에 이목이 더 쏠린 듯한데, 그들의 시선이 그쪽에 멈춰 있다. 파탄에서는 화면을 가로질러 날아가는 새 떼와 주민들의 차분한 평온함이 대조를 이룬다. 파탄에서 움직임 없는 작가의 형상에 이끌린 이들은 주로 아이들이다. 하바나에선 한 남자가 그를 보고 얼굴을 찌푸리는데, 다수는 미소를 짓고 일부는 걸어가다 무어라 말을 한다. 사나에서는 남자들, 특히 젊은 남자들(거리에서 여성은 거의 찾아볼 수 없고 있더라도 검은 장옷에 눈 부분만 트인 스카프로 온몸을 가리고 있다)이 그를 둘러싸고는 유심히 쳐다본다. 은자메나에서, 작가의 형상은 사람들의 각양각색 옷이 빚어낸 색의 매스와 군중이 움직이며 자아낸 리드미컬한 일렁임 속에 녹아든다. 머리에 짐이나 통을 지고 지나던 사람들은 작가를 둘러싸고 발걸음을 멈추어 가만히 보다 손짓으로 인사를 건네고 말을 걸기도 하는데 무어라 질문을 던지는 듯 하다. 그들의 얼굴에 떠오른 호기심이 분명히 보인다. 그들의 행동을 지켜보는 단순 관찰자일 뿐인 우리는 기대하는 마음으로 바라본다. 작가의 존재에 사람들이 어떤 반응을 보일지 어쩔 수 없이 약간은 긴장하게 된다. 언제라도 갑자기 폭력이 일어날 수 있다는 사실을 알기에, 불시의 일이 일어날까 두려운 마음이다. 하지만 전개되는 상황을 보고 있노라면, 자신을 향한 시선과 미소와 이런저런 말에 과연 작가 본인은 어떻게 반응하는지가 궁금해진다. 놀란 행인들이 무슨 말을 하고 있을지도 궁금하다. 뜻밖에 나타난 작가의 존재에 입 밖으로 나왔을, 하지만 막상 우리가 들을 수는 없고 추측할 뿐인 그들의 말이 궁금하다. 우리는 더 알고 싶다. 사람들 사이에 함께 서서, 우리 나름의 결론도 내려보고, 사람들 의견은 어떤가 파악하고, 과연 뜻밖에 마주친 저 부동의 여인에게 사람들 마음이 끌린 건지 아니면 불안하거나 당황스러운지 알고 싶다. 물론 사람들의 반응을 관찰할 수는 있다. 사람들이 카메라의 시야로 걸어들어와 무심코 주인공이 될 때 카메라가 얼굴을 보여주기 때문으로, 대체로 존중하는 반응이다. 하지만 동시에 본능적으로 우리는 행인들이 무슨 말을 하는지 듣고 싶어 한다. 작가는 자신을 드러내고 또 우리를 드러낸다. 작가를 관찰하는 우리 역시 군중에 열린 존재가 되어, 사람들의 반응을 새기며 작가와 함께 군중과 하나로 합쳐든다. 하지만 우리는 언제나 더 알고 싶다. 그들이 드러내는 개별성의 작은 단서를, 이 세상에 존재하며 그들이 발하는 작은 불꽃을 말이다.

-

사람들이 보이는 행동과 그들이 작가와 마주치며 보이는 표정과 반응을 통해, 김수자는 다른 나라에서 다른 사람들이 실제로 어떤 상황 속에 살아가는지 우리의 이해가 얼마나 제한적인지를 체험하게 한다. 작가는 나라마다 사람마다 그 사이에 놓인 최소한의 차이를 탐구해, 무엇이 어느 하나를 나머지와 구별 짓는지를 짚어내려 한다. 그는 무작위로 퍼포먼스를 진행할 도시와 국가를 고른 것이 아니다. 김수자의 선택은 포스트식민주의, 내전, 국경 분쟁, 극심한 빈곤으로 촉발된 해당 지역의 갈등을 그가 인식하고 있음을 보여준다. 하지만 김수자는 지치고 노쇠한 유럽과는 전혀 다른 곳, 그토록 갈등에 시달리며 알 수 없는 상황과 날카롭게 맞서는 곳에서 슬픔을 발견하고 영감을 얻는 듯하다.

-

이 모든 비디오에서 김수자는 반복되는 상황과 변치 않는 자신의 이미지를 연속하여 제시함으로써 이 세상에 자신의 존재를 각인시킨다. 사람들의 신체적, 물리적 존재는 자연과 마찬가지로 그의 작업 속에 침투한다. 사람들은 세상에 다양한 존재 방식이 존재하고 우리가 고독한 존재임을 표명하는 동시에, 세계란 언제나 존재하고 있으며 우리는 타인에 둘러싸여 살아간다는 사실을 일깨운다. 김수자의 작업을 두고 젠더 문제로 지나치게 단순화하는 시각이 있지만, 그의 작업은 젠더 문제를 훨씬 넘어선다. 그는 우리가 살아가는 이 혼돈의 세계 속에서 인간으로 존재한다는 것이 중요한 이유를, 그 모든 고독과 덧없음까지 함께 보여준다. 직접적으로든 간접적으로든, 인간이 남긴 흔적, 즉 사람들의 '발자국'을 통해 인류는 김수자의 작업에 언제나 존재한다.

-

정치적 문제에 직접 맞서는 것이 그의 관심사는 아니지만, 인간이 처한 상황과 현실을 향한 그의 시선은 종종 정치적, 사회적 사건과 분명 연관된 설치 작업으로 이어졌다. 때로는 사건에 대한 반응이고, 때로는 그에 관한 기억의 구성이며, 희생자에 대한 오마주이기도 하다. 제1회 광주 비엔날레에서 선보인 <바느질하며 걷기(Sewing into Walking)>(1995)는 공원의 땅바닥에 흩어 놓은 헌 옷가지와 보따리들로 구성되어 있는데, 그 모습이 마치 전장에 널브러진 시신 같다. 이 작품은 1980년 5월 광주에서 민주주의를 위해 싸우다 목숨을 잃은 수백 명의 광주 학살 희생자에게 헌정되었다. 일본 나고야 시립미술관에서 선보인 <연역적 오브제 – 내 이웃에 바침(Deductive Object – Dedicated to my Neighbors)>(1996)에서는 한국인과 일본인의 옷가지들이 섞여 있다. 같은 해 작가의 동네에서 벌어진 서울 삼풍백화점 붕괴 사고 희생자에게 바치는 의미를 담은 작품이다. 제48회 베니스 비엔날레에서 전시한 <모든 것에 열린, 혹은 망명의 보따리 트럭(D'APERTutto or Bottari Truck in Exile)>(1999)은 색색의 보따리를 가득 실은 트럭 앞에 거울을 설치하여 트럭의 거울상을 보여준다. 거울이 끊임없이 공간의 열림을 창출하지만, 거울은 제 앞에 열린 트럭의 길을 스스로 막고 있다. 코소보 내전 난민에게 헌정된 이 작품은 당시 베니스에서 불과 몇 킬로미터 떨어진 곳에서 벌어지고 있던 강제 이주, 죽음, 파괴 등 전쟁의 참상을 상기시켰다. <묘비명(Epitaph)>(2002)은 2001년 9월 11일에 일어난 사건에 응답하여 선보인 작품이다. 감성적이고 아름다운 이 강렬한 사진 속에서 작가는 브루클린 그린론 공동묘지 땅 위에 색색의 이불보를 펼쳐 놓는다. 살아있는 자의 비석과도 같은 맨해튼 스카이라인을 배경으로 쌍둥이 빌딩이 사라지고 남긴 거대한 빈자리가 보인다.

-

작가로서 활동한 내내, 특히 최근 몇 년 사이 김수자는 설치, 사진, 퍼포먼스, 비디오 작업과 더불어 장소특정적 프로젝트에 참여해왔다. 천, 특히나 눈길을 사로잡는 한국의 이불보, 빛과 색의 시퀀스, 티베트 · 그레고리오 · 이슬람 수도자들의 성가, 작가 본인의 숨소리 등이 작업의 주요 수단으로, 그의 작업임을 알리는 특징이 되었다. <심겨진 이름들(Planted Names)>과 <등대여인(A Lighthouse Woman)>(2002)이 그러한 사례로, 노스캐롤라이나 찰스턴에서 열린 스폴레토 페스티벌 USA 2002의 일환으로 설치되었다. 김수자는 찰스턴이라는 식민지 수도의 세계도시적 성격과 도시의 해양 유산을 일깨우는 《물의 기억》전시에 참여했다. <심겨진 이름들>은 드레이튼 홀 농장에서 일했던 노예들을 기리는 한편, 군인 장교의 딸로 비무장지대에서 자라 이후 가족과 이 도시에서 저 도시로 이주하며 성장해온 작가 본인의 이야기를 반영한다. 네 장의 검은 카펫 위로 드레이튼 홀 농장에서 노예해방 때까지 일했던 아프리카 출신 노예들의 이름이 흰 글자로 두드러지게 적혀 있다 . 드레이튼 홀 1층의 대형 홀 주변의 방마다 설치된 카펫은 공간을 변화시켰다. 작품이 설치된 드레이튼 홀은 미국에 현존하는 가장 오래된 농장 저택으로, 조지안 팔라디안 건축 양식의 보물로 여겨지며 보존 중인 건축물이다. 과거의 묵상으로서 카펫은 자유를 박탈당한 이들의 기억이 특히 울림을 주는 공간에 전략적으로 배치되었다. <등대 여인>에서 작가는 빛과 색과 바다소리를 사용해 사우스캐롤라이나 찰스턴의 모리스 섬에 버려진 등대를 기념비로 변모시킨다. 모리스 섬에서 벌어진 남북전쟁의 희생자를 기리는 이 작품은 등대 자체가 상징하는 빛과 물의 영원한 관계에 바치는 헌사이기도 하다.

-

비엔나 쿤스트할레에서 전시된 <빨래하는 여인(A Laundry Woman)>(2002)은 다채로운 이불보와 티베트 승려들의 독경 소리로 구성되어 있다. 거대한 창문을 통해 쿤스트할레 바깥에서 이불보를 볼 수 있는데, 마치 빨랫줄에 빨래를 널듯이 설치되어 있다. 이불보는 여성의 역할을 나타내는 은유로 기능하며, 쿤스트할레의 내부 공간과 바깥의 도시 풍경, 더 나아가 삶과 예술, 내밀함과 보편성 간의 대화를 형성한다.

-

제2회 발렌시아 비엔날레 측은 김수자에게 도시 안의 빈 부지를 활용한 설치 작업을 청했다. 그렇게 탄생한 <솔라레스코프(Solarescope)>는 건물에 다변하는 오방색의 빛 시퀀스를 영사한 작품으로, 버려진 부지에 생명력을 선사했다. 프랑스 릴의 라모 팔라스에 설치한 <로투스 – 0의 지점(Lotus: Zone of Zero)>(2003)은 307개의 연등과 음악으로 구성된 작품이다. 붉은 연등이 연꽃 모양으로 배열되어 건물의 원형 홀에 매달려 있다. 그리고 공간 속으로 티베트, 그레고리오, 이슬람 성가 소리가 흘러 넘친다. 눈길을 사로잡는 설치의 아름다움을 넘어, 인간 존재 사이에 평화와 사랑과 이해를 촉구하는 작품이다.

-