2017

Jérôme Sans │ A Journey through Immobility

2017

Young Hee Suh │ Geometry of Mind and of Body

2017

서영희 │ 몸과 마음의 기하학

2017

Sungwon Kim │ Archetype of Mind

2017

김성원 │ 마음의 원형

2017

Steven Henry Madoff │ Kimsooja: The Task of Being-Together

2017

스티븐 헨리 마도프 │ 함께-있음의 과제

2017

Hou Hanru │ Create A New Light

2017

후 한루 │ 새로운 빛을 밝히다

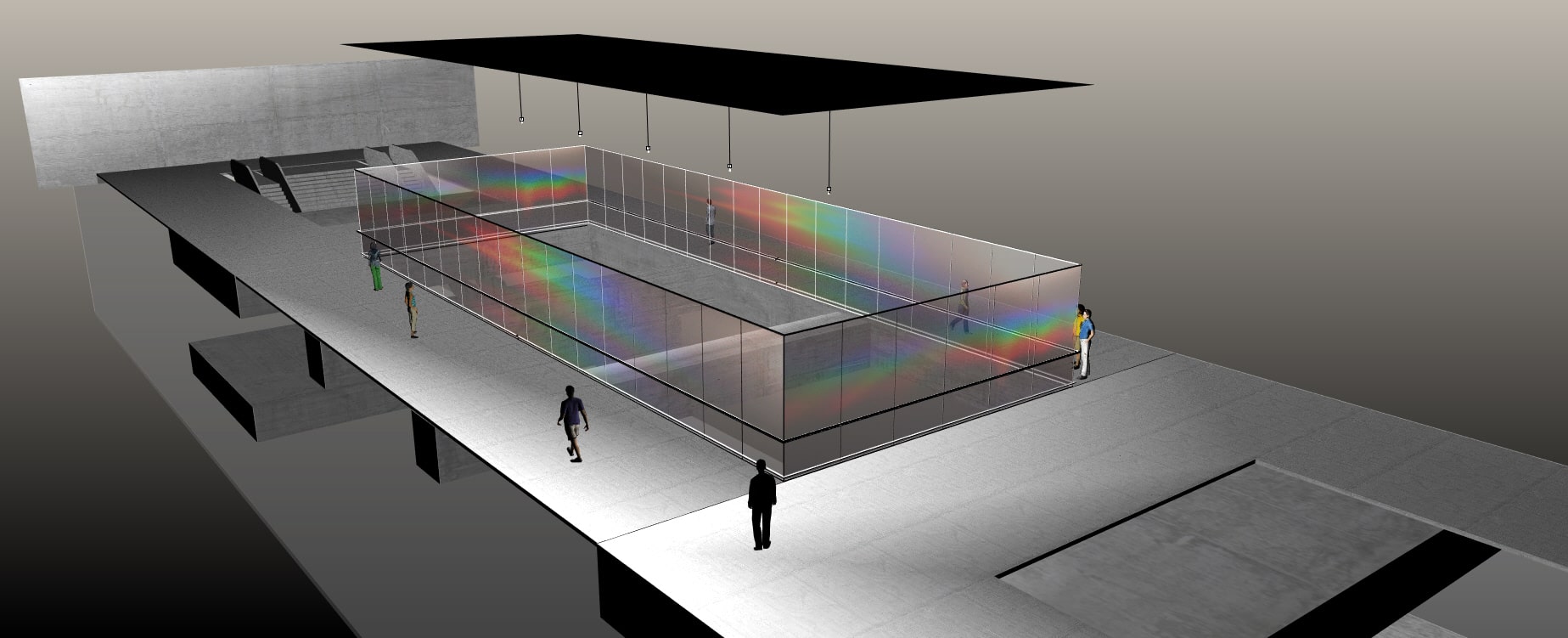

To Breathe, 2017-2021, Rendering of the Site Specific Permanent Installation, Mairie de Saint-Ouen Metro Staion, Paris, France. Commission of the RATP Régie autonome des transports parisiens. Courtesy of the RATP and Kimsooja Studio

To Breathe, 2017-2021, Rendering of the Site Specific Permanent Installation, Mairie de Saint-Ouen Metro Staion, Paris, France. Commission of the RATP Régie autonome des transports parisiens. Courtesy of the RATP and Kimsooja Studio

A Journey through Immobility

2017

-

Jérôme Sans

How would you define your work? -

Kimsooja

I view my work as a threshold: “any place or point of entering or beginning, a magnitude or intensity that must be exceeded for a certain reaction, phenomenon, result, or condition to occur or be manifested.” -

Jérôme Sans

Would you call some of your works self-portraits? Is it important that you yourself are in some works? -

Kimsooja

In some ways, my work could be viewed as a self-portrait. I do not wish to display my personal identity in my work—especially in the video performances when my back is facing the viewer—but the position demonstrated does show a certain kind of identity. I think a person’s back can be one of the most evocative parts of the human body; it isn’t dynamic, but it presents a profound and abstract encapsulation of a person. -

Jérôme Sans

How do you consider the globalized world? -

Kimsooja

A globalized world sounds very positive, dynamic, interconnected: a constant flow of cultural, economic, technological, and intellectual interactions. But we face many visible and invisible divisions created by constant border crossings: racial, economic, political, and religious conflicts. The standardization of daily life under globalism could benefit those who need it most, but we lose the authenticity, spirituality, and the myth of a land and its people. Globalism reduces the uniqueness and specificity of humanity, although new technology will bring a new facet. -

Jérôme Sans

What do you think of migration today? -

Kimsooja

More than five million Syrians have migrated to Greece, Turkey, Germany, and nearby countries; there is a constant flow from Africa to Southern Italy and Spain; people from Mexico and Central and Latin America try to get to the United States. As an artist who has always been concerned with borders, migration, and refugee issues, especially from living near the Korean Demilitarized Zone during my childhood, I am shocked by President Trump’s decision to block borders, deny immigrants a new life in the United States, and deport second-generation immigrants. American citizens have to pay attention to this humanitarian issue, especially since only a few organizations and individuals are focused on the refugee crisis. Major European countries are taking risks to support and help the refugees. Along with global warming, it is the most urgent issue of our time. -

Jérôme Sans

Your work deals with exile and displacement. Do you feel exiled too? -

Kimsooja

Definitely. I have considered myself a cultural exile since 1999. Recently, I’ve collaborated with Korean-specific projects, such as Année France-Corée for a solo show at the Centre Pompidou-Metz in 2015 and the MMCA Hyundai Motor 2016 project. Still, my position as an artist remains that of an outsider rather than insider, even though I’ve been well received. Perhaps it is the fundamental nature of being an artist? -

Jérôme Sans

You have lived in New York for several years, how have things changed for you? -

Kimsooja

Thanks to support from Arts Council Korea in 1992, I was able to participate in the P.S. 1 studio residency program in New York. I met people who understood my work and viewed it objectively, with enthusiasm and generosity. It really opened up possibilities for me. Due to the Korean financial crisis in the late 1990s, I was not able to receive financial and intellectual support for my work. It truly disappointed me and made me realize that I needed to find support outside Korea. -

In the last ten years, this has changed dramatically and Korea is now one of the most supportive countries in the world. However, when I go back to Korea, I am too established to get support from my country. The level of professionalism still needs to be raised, especially in governmental organizations. Where to live, work, and die are big questions. You need a nation to live—but you don’t need a nation to die.

-

Jérôme Sans

The idea of displacement is very present within your work. -

Kimsooja

All good art is made from thinking outside the box. In that sense, having displacement as a condition of life is not a bad choice for an artist. -

Jérôme Sans

In some of your works, like A Needle Woman (1999–2001, 2005, 2009), immobility rather than displacement is present. Is it a way to show personal identity toward the global world? -

Kimsooja

In my practice, the notion of duality and its complex geometry and disorder are always present through my understanding of the world. While I am presenting my immobility, which is impossible in literal terms, a lot of mobility happens in my body and mind, allowing me to reach to the place and moment of my performances. This immobility gives me an anchor to hold onto, so my journey flows through immobility. -

Jérôme Sans

Some of your works and installations are made with bottari, meaning, “to pack for a trip.” Which trip are you addressing? -

Kimsooja

The bottari represent our body and skin, their agony and memory as a wrapped frame for life. Bottari are the simplest way of holding objects or belongings that embody many meanings and temporal dimensions. A trip could be a simple A-to-B, or a relocation, or a separation of a couple in feminist terms, wrapping only the most essential belongings in an emergency—migration, exile, or our final journey: death. -

Jérôme Sans

Do you consider yourself as a nomad? -

Kimsooja

Yes, fundamentally. -

Jérôme Sans

Your work is an invitation to a sensorial and visual trip—a way to travel without moving. -

Kimsooja

We can easily grasp what is going on in this hyper-informed society, but we can’t experience true reality, not in depth. All experiences are limited by the conditions of space and time; I am determined to witness the here and now, living through my eyes and body, sharing my experiences with the audiences. -

Jérôme Sans

In the emblematic work, A Needle Woman, you stand in moving crowds. Who was this needle woman? And who is she now? -

Kimsooja

A Needle Woman is a woman who gazes at the world, gazing at and witnessing the world without acting. She allows us to take a journey to reality and reach for the ontological root—our destiny. She is there as a tool, a question, a permanency; I am here as a temporality. -

Jérôme Sans

In your installation To Breathe – A Mirror Woman (2006), shown in Madrid, we can hear your own breathing, filling the space. What is your relationship to the body and the act of breathing? -

Kimsooja

I’ve always reinterpreted and recontextualized existing concepts, depending on the site, the questions I had, and the relationship to other works and sites. This installation has three different components from past projects. The Weaving Factory (2004), was my first sound performance, I overlapped my breathing and humming; it developed from the idea of my body as a weaving machine, inspired by an old textile factory in Lodz, Poland, for the First Lodz Biennale. Later, I worked on a video installation commissioned by Teatro La Fenice, Venice, called To Breathe (2006), which incorporated The Weaving Factory. La Fenice is an opera house and singing is about breathing. When I was invited to make a work for the Palacio de Cristal in Madrid, I brought all of these elements together, contextualized as a bottari and as a void. Attaching the diffraction film to the architecture was an act of wrapping and unfolding the daylight into a rainbow spectrum. -

Jérôme Sans

One of your upcoming projects is a work for the new subway station at Mairie de Saint-Ouen in Paris. -

Kimsooja

Although it is a site-specific and permanent installation, this project brings me back to the body/work and audience/pedestrian relationships in A Needle Woman. This installation will symbolize another body of mine, one that witnesses the station’s pedestrians. The diffraction film installation will function as my body, standing still in the station and witnessing the pedestrians, while offering the public a forum. -

Jérôme Sans

You were teaching at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. What is your connection to Paris? -

Kimsooja

Paris was the first western city I visited; I stayed for six months in the mid-1980s. A scholarship from the French government allowed me to work at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts in the lithography studio. Whenever I had a project in Europe in past thirty years, I’ve also visited Paris, even if I didn’t have any particular reason.

During my six-month stay in Paris, I traveled to other European cities for the first time, visiting major museums in Germany, Italy, Holland, and England. I was 27 years old. I absorbed the language, art, culture, and life in Paris, they are forever in my memory. In 1985 at the Biennale de Paris, I first encountered John Cage’s work. Although I knew of him as an avant-garde composer, I had never heard his music live, or seen any of his visual works. With great curiosity, I entered an empty railway car to hear his sound piece, but there was only silence and a simple written statement, “Que vous essayez de le faire ou pas, le son est entendu” (“Whether we try to make it or not, the sound is heard”).

It was interesting that I learned so much from an American avant-garde composer, rather than from European art or artists, although I was aware of the French Supports/Surfaces group and the influential artists at the time. After my encounter with Cage’s work, I became curious about American art and culture for the first time.

I’ve shown quite often in France, the French government and institutions have supported many of my works, and I owe them a lot. I was admitted to the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres by the Minister of Culture for my modest contribution to French culture. I have a love for Paris and French culture and want to spend more time working there. -

Jérôme Sans

What new avenues are you exploring? -

Kimsooja

Since 2010 I’ve been working on a 16mm film series titled Thread Routes, filming textile cultures from around the world: Peruvian weavings (chapter I), European lacemaking (chapter II), Nomadic Indian textiles (chapter III), Chinese embroidery (chapter IV), Native American weaving (chapter V), and African textiles (chapter VI). I can’t wait to visit Africa to film soon. Since 2016, I have realized a large-scale participatory installation titled Archive of Mind, firstly for a solo exhibition at the National Museum for Modern and Contemporary Art, Seoul, as part of the MMCA Hyundai Motor Series. This project is evolving and was presented at the Intuition exhibition at Palazzo Fortuny in Venice this year, and opens up to explore the sculptural aspect of my practice from the position of a painter. -

There is also a new installation at Nijo Castle, Kyoto, commissioned by the Culture City of East Asia, with the title Asian Corridor; it’s a ten-panel folding mirror screen on a mirrored floor, entitled Encounter – A Mirror Woman (2017). This is my second East Asian City project, the first, in Nara, was Deductive Object (2016), a black sculpture, inspired by an Indian ritual stone called Brahmanda (a cosmic egg in Hindu culture), installed on top of a mirror panel.

-

These works redefine the geometry of bottari and the surface of the symbolic bottari that represents the totality of the universe. I want to explore further what this could bring to my future practice. I am also starting new clay works. All of these are exciting, new directions to keep exploring, and I am very curious about the outcome.

-

Jérôme Sans

How do you see the future? -

Kimsooja

The future doesn’t exist anymore—it is past.

— Kimsooja: Interviews Exhibition Catalogue published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König in association with Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, 2018

- This interview was conducted in summer 2017 via email in conjunction with one of Kimsooja’s upcoming projects, a work for a new subway station in Paris.

A Study on Body, 1981. Silkscreen Print on Paper, 34 x 34 cm. Courtesy of Kimsooja Studio.

A Study on Body, 1981. Silkscreen Print on Paper, 34 x 34 cm. Courtesy of Kimsooja Studio.

Geometry of Mind and of Body

Young Hee Suh (Professor, Hongik University)

2017

-

For her special exhibition at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Korea in the Hyundai Motors Series 2016, Kimsooja presented nine artworks, including her most recent, which were displayed in the Exhibition Hall 5 and in the courtyard of the Museum’s Seoul branch from July 27, 2016, to February 5, 2017. The exhibition featured artworks of diverse media, both two-dimensional and three-dimensional works, installations, and audio and video. This exhibition offered a rare opportunity to appreciate the breadth of the artist’s work scope and varied use of materials.

-

Kimsooja is an established, mid-career artist who has been internationally prominent for almost thirty years. In her previous exhibitions, she has used diverse media and implemented creative ways of installing artworks. Audiences have admired her endeavours to push the envelope of her own creative domain, and had high expectations for what the artist would convey on this occasion. In the titles Kimsooja chose, she deliberately asked viewers to ponder certain meanings in her art. She called the two most prominent works in the exhibition Archive of Mind (Geometry of Mind in Korean) and Geometry of Body, which established an overarching theme that extended throughout the exhibition. This was an invitation for the viewers to look at each piece in the context of either the expansion of body or the expansion of mind. More specifically, viewers were confronted with a dualistic interplay of mind and body. Through the visual extrapolation of these two contrasting but inextricable concepts, Kimsooja unfolded a realm in which one could reflect on the relationship between the substantial and the insubstantial, between the inside and outside of being, or between the self and the world.

-

The artist chose to title the exhibition bilingually: its Korean title, Maeummui gihahak, or Geometry of Mind, together with its English title, Archive of Mind, hinted that the exhibition was more than an illustration of the sensory employment of medium or an experimentation with forms of expression. Rather, the exhibition revolved around the metaphysical notions of mind and body. Serious viewers would realize that her goal in this exhibition was not to differentiate her artistic present from the past by demonstrating certain expressive forms in unexpected or unprecedented ways. They were expected to focus on very specific messages that Kimsooja’s artworks signify and find themselves asking questions like: What is the fundamental motivation for her art-making? What is the consistent theme that runs through her works in this exhibition? How should such profound-sounding titles be construed? This essay aims to help the reader revisit these questions and, in the process of seeking answers, come upon discoveries both intended and serendipitous. This would help us experience the epiphany Kimsooja wished to share with all of us through her reflective project at the National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art of Korea.

-

In most of the writings on Kimsooja, her work is interpreted through conceptual frameworks borrowed from such disciplines as cultural anthropology, psychology, philosophy, religion, sociology, or feminism. This study does not stray far from those frames of reference, but differs in its focus on the concepts of body and mind as manifested in Kimsooja’s art — a viewpoint that has not been pursued in the past. It specifically strives to expound the relationship between mind and body from the perspectives of both Eastern and Western philosophical traditions; I will try to interleave East Asian and European thoughts in relation to the concepts in Kimsooja’s works. Kimsooja has arranged each bundle of her ideas in non-contiguous spaces, which then have to be stitched together with a metaphysical thread across the gaps of discontinuity. This study is organized in the same way — that is, in a structure of non-contiguous thoughts and their synthesis across the discontinuous boundaries to propose a new condition of contemplation.

Body and Mind: Monistic Dualism

-

The concept of mind is inherently difficult to grasp. In general, the term mind refers to a person’s personality or character; but it can also mean a metaphysical space that contains a person’s thought or emotion. In English, mind represents the spirit or thought of the brain. The corresponding French word âme means soul or consciousness. The meaning of mind differs somewhat whether the Korean or English term is used. This divergence is probably a result of differences in Eastern and Western thought. In many traditions of European origin, mind and material have been disparate concepts. Mind is a human attribute whereas material is an attribute of things. The human mind stands independent of the external, material world and is subject to rational principles, thus forming a dimension that is separate from the material world, to which the body belongs. This way of thinking is called dualism of mind and body, predicated on the premise that mind and body are independent of each other. However, Eastern thought is not compatible with this kind of dualism. In East Asia, mind and material are deemed interdependent or complementary to each other, forming an inseparable relationship. This view, which has become the basic underpinning of philosophical thinking, treats mind and body as two different manifestations of the same entity. It does not hold that the mind governs over a body seen to be inferior. This is a monism of mind and body, or monistic dualism. According to this view, mind and body originate in and ultimately fuse and return to the state of being one. Oneness is deemed as the fundamental principle of the whole universe; it corresponds to the Great Ultimate (??, taiji) in the Confucian book the I Ching or Yijing (??, Classic of Changes), the universal and absolute principle (?, li) in the teachings of Neo-Confucianism, and nothingness (?, kong) in doctrines of Buddhism.

-

Recently, a monism of mind and body has been accommodated by many European thinkers, one of them being Jean-Luc Nancy. In his book Corpus, Nancy focuses on the disparaged status of the body in relation to mind, and attempts to rebalance the conventionally lopsided relationship between the two. The premise of his claims is that the body is der einzelne, meaning that it does not exist in the dominion of the mind, nor is it an existence that is merged with the mind. At the same time, he repudiates the concept of body that is perceived as the opposite to soul or mind. Nancy’s “body” is not a foreign or unfamiliar object to an inner soul (âme, psyché) but a correlator that coexists with soul. To paraphrase, body is the expansion of soul and at the same time the exterior of soul. According to Nancy, the body is opened toward the outside, i.e., it is revealed and unfolded outwards. The body is the soul’s expansion toward the exterior and forms itself as the Other (l’autrui). The soul or the mind, then, is the inner substance of the outer body and, as such, supports the body’s sense of contact. Body and soul form an oppositional pair to each other. This is a monistic dualism as the relationship between body and mind.

-

The concept of mind cannot be apprehended by logic or be defined by certain categories or boundaries. In order to discern the concept of mind beyond this impossibility of knowing or the limit of our rational capacity, one has to dispense with the belief in the mind’s self-sufficiency and experience a break from the closed, egocentric self. One must see that the mind is opened toward the outside — the outside which may be called the body, the Other, and the world or the universe. The process of the mind opening up or unfolding toward the outside — thereby breaking out of the subject-centred closedness that endlessly collapses inwards — is what Nancy calls as the expansion of the soul. Through such a process, the soul transcends the limitation of being immanent in itself and enters what both Emmanuel Levinas and Nancy describe as the altruistic coexisting relationship of “being-with.” The characterization of the relationship between mind and body (soul and body) as “being-together” parallels the concept of the “pluralistic singular existence (être singulier pluriel),” which is the essence of ourselves in society. Rather than expand on the relationship of pluralistic singular existence to the democratic community, I intend to connect this concept to the monistic dualism of material and mind, material and non-material, and, by extension, to the monistic dualism of finiteness and infiniteness.

-

In his discourse on the expansion of the soul, Nancy set out by addressing the issue of the body among the many facets of the Other. He argues that when the soul tries to reach the body, which is its own Other, as well as the outside, the soul contacts itself through the outer skin of the body, which is its own exposure (l’exposition du soi, l’expeausition). Owing to the ego outside the ego and the body that is the boundary between the self and the world, the soul is able to maintain its balance without leaning toward the inside or the outside. The concept of body, which stands as neither a subject nor an object, in conjunction with the idea of a balanced soul, offers a valuable clue to understanding Kimsooja’s works in this exhibition.

-

Nancy’s expansive argument about body and soul leads to a discussion of the existential finiteness of the body and its coexistence in a social context. However, in Kimsooja’s Geometry of Body, the finite coexistence of people is not a matter of importance; her focus is on our original existence that confronts the absolute or the infinite. In that regard, Kimsooja’s work diverges from Nancy’s discourse. Additionally, as a means of approaching the infinite that is the limit of existence, most of Kimsooja’s works involve geometrical structures and a balance that symbolically signify the monistic dualism of body and soul. The geometric balance, with its primordial power, brings about an effect by which we are almost unconsciously drawn into the world of the absolute and the infinite. Facing the overwhelming infinite or absolute, we are awakened from the state of our everyday existence and compelled to turn our eyes towards our original existence. We either avoid facing death or lead a life oblivious to it even though the inevitability of death is embedded in the very foundation of our present existence. If existence comes to grips with death through a constant ontological anxiety, it is said to be in fundamental and inherent authenticity (Eigenlichkeit). It was the philosopher Martin Heidegger who set out this ontological perspective and touched on the issue of “authentic existence” in Sein und Zeit (Being and Time). This authenticity of being metamorphoses the state of everyday “being there” (Dasein) into authentic existence. An authentically finite self anticipates its eventual death and projects (Entwurf) itself into authentic being, thus breaking from the self-contained self.

-

In my view, the concept of authentic being is closely aligned with the monistic dualism of mind and body. A human being conceived as a dualistic entity of mind and body is an existence placed on a path to absolute nothingness, or death. Of course, death in Western existentialism is the negation and perishing of being. Little or no attention is paid to the state beyond death. Even though Dasein anticipates its own death, it does not pursue the absolute domain that death ushers in. In contrast, traditional Eastern thought does not consider the death of body and soul to be a perishing, but as either a threshold through which existence enters the absolute world or a stage where existence is united with the infinite world. Therefore the meaning of existence expands to the dynamic absolute (taiji) or nothingness. While the East and the West may differ in their answers to what constitutes authenticity of being, both affirm death to be instrumental in opening up the complete possibility of being, or the ultimate infiniteness that establishes the meaning of our existence.

The Meaning of “Geometry”

-

The monistic dualism of body and mind provides an effective framework when we seek to grasp the significance of “geometry” as specified in the titles of works such as Geometry of Body and Geometry of Mind. It is obvious that the artist did not intend geometry to be a mathematical study dealing with figures or space. Kimsooja’s geometry is an intuitive method to help visualize complex ideas around the metaphysical notions of body or mind. The artist, by employing such a geometric method, reminds viewers of the dualistic and agonistic structure of body and mind — or the dualistic structure of material and consciousness, of the finite and the infinite, and of authenticity and non-authenticity of being. Furthermore, through geometric structure, Kimsooja leads each viewer to think of possible aspects of being. Geometry in this case can be understood as a statistician’s method that transforms a great deal of complex information into visual models, or a logician’s method of deductive reasoning in which concrete and evident facts are laid out as the ground for general principles. This methodological approach has helped the artist to avoid being lured into subjective, emotional traps while rendering images and objects in the visual arts. Kimsooja could better convey her ideas to the viewer thanks to intuitive clarity and deductive facility offered by this geometric method. Thus we could argue that her works can be categorized as conceptual art.

-

Verticality and horizontality, as key elements of a geometric structure, can effectively represent the ideas underlying a monistic dualism of the body and mind. Since the early 1980s, Kimsooja’s works almost without exception have a structure of verticality and horizontality, with intersections of longitudinal and transversal lines in an orderly fashion. The structure of perpendicular lines intersecting each other and extending in opposite directions displays a sense of expanding movement that unfolds toward infinity, while maintaining balance in the four cardinal directions. This structure creates an open-ended space in which the inside communicates with the outside and movement can take place in any direction. When a vertical and a horizontal line intersect, the four directions come into being. As lines are added through that intersection, the number of directions increases to eight, sixteen, thirty-two, sixty-four, and so on. In traditional East Asian philosophy and religion, these numbers signify time and space. In the Yijing, the sacred book of Confucianism, sixty-four trigrams symbolize sixty-four directions and represent divergent attributes of being. In the Buddhist scripture Taejanggaemandara, the eight lotus petals called jungdaepalyeobeon — which contain the four Buddhas of east, west, south and north and the four Buddhas of the northeast, southeast, northwest and southwest — symbolize the omnipresence of Buddha throughout the universe. Additionally, the eight or sixteen spokes of the wheel represent the Buddhist Dharma that permeates all directions of the universe. It is also the archetypal image of wonyoongmuae, which means “all things in all directions with no obstructions and in perfect integration.” The vertical and horizontal structure underlying all these concepts may be viewed as the dualistic structure of yin and yang or of heaven and earth, symbolizing the universe as an unhindered infinite space.

-

The concept of cheonjiinsamjae, as expounded in the Yijing, offers an interesting perspective on how the universe functions in relation to human beings. It adds the human being to the dualistic order of heaven and earth. Even though the universe initially comprised these two fundamental elements, human beings have come to be an indispensable mediator between heaven and earth, enabling the universe to function at its full capacity. A dualistic view of heaven and earth presumes that the world is just spread between the earth and the sky does not accommodate the use of the human mind, and is devoid of any engagement with human mind or attention. In contrast, the theory of samjaeron, the theory of three generative forces, asserts a role for human beings in the operation of heaven and earth. It raises the status of human beings to the same level , while asserting that human beings are the linchpin that holds together the universe. The inclusion of humans alters the traditional view of nature into a humanistic view of the world. Owing to this shift of views, nature philosophy in the East evolved into a humanistic moral philosophy, as manifested in Confucianism. The Doctrine of the Mean, written by the Confucian scholar Zisi, states that a human being is able to assist in change and operation of the universe and, if he or she is willing, can participate in the ranks of the three generative forces. For this, a person should perfect his or her own “human identity” bestowed by the universe. The Doctrine of the Mean dictates that it is imperative for human identity to be in compliance with the principles of the universe, or li. This is called the axiom of sungjeuklee, which means “human identity equal to the principle of the universe,” and is considered the core proposition of Confucianism. Therefore people should always cultivate their own body and mind so that their human identity is in sync with the principles of the universe — that is, in the state of golden mean. This is a state of balance maintained by a steady mind that does not get disturbed or swayed in any direction. A person in the state of golden mean attains his or her original identity, which is aligned with the principles of the universe, and can effectuate a harmonious world. If the human, who is a significant medium in helping to change and operate the world, is absent or disengaged, what would become of the world? Then, heaven and earth would remain indifferent to each other, separate, without relation, which brings us back to a dichotomous dualism. With humans engaged in conscious efforts to realize the principles of the universe, a dualistic structure is replaced by a monistic dualism of the world.

-

Although humans are finite beings, as mediators, they have the potential to reach for heaven in vertical relations and traverse the earth in horizontal relations. The vertical-horizontal structure defines our infinite universe. The encounter of yang, the spirit of heaven, and yin, the spirit of earth, procreates living matter and entities. Of these, only humans can join as the third of the three generative forces of the universe and engage in the operations of heaven and earth. Humans are capable of giving unitary interpretations of the world and of nature, as only humans have mind. According to the Doctrine of the Mean the ideal state of existence is the golden mean, which is alternatively called the middle or composure in the sense that it is the harmonious middle between yin and yang. The notion of composure resonates with ataraxia — “imperturbability,” the composed and stable state of mind and body sought after by the Epicurean School of ancient Greece. They believed human happiness exists in the state of ataraxia just as Confucian scholars asserted that if humans abide by the rule of the golden mean they are able to live a life that is delightful, worry free and happy, a life in which they perceive their own humanity without imbalance or bias.

-

The geometry of vertical and horizontal structure embodies a state of calm and composure that does not tilt to one side — this composure of body and mind is similar to what Confucianism pursued. The most fitting image of the stability of mind and body in the state of composure would be one of a vertical and horizontal structure in balance. Kimsooja may not have intentionally predicated her works on the propositions of Confucianism or, more precisely, Neo-Confucianism, however, it cannot be denied that her framework parallels them quite aptly. Just as Heidegger argued for the existential being to be authentic (to stay in existential anxiety by facing death and thereby overcoming the dualism between existence and nothingness), Confucian philosophies pursued a more positive human existence that communicates with the infinite and the absolute — a spatial and temporal realm that cannot be experienced. Confucianism in particular emphasized the universe as the root of the beginning and end, of the world of yin and yang. The basic tenet of Confucianism lies in the harmonization of human identity with the cardinal rule of the universe and living a balanced life in accordance with the order of yin and yang.

-

Kimsooja’s Geometry of Mind, an installation that was shown for the first time in this exhibition, prompts us to closely analyze the mind and realize it indeed is unified with the body as one and at the same time is related to authentic human identity. As there is no way to define this mind, we instead have to observe what state the mind exists in. When we observe our own mind, we realize that it initially has no shape or movement — it exists in a state of potential. It is only when a stimulus enters that the mind moves and arises; it oscillates to the state of reality filled with perception and emotion. The mind’s tranquil state of potential, while traversing through the time and space of our reality, transforms into a state of “being real” and reveals itself in this process. One of the annotations to the Yijing refers to the state of mind that has not yet been revealed to the outside as “the mind being calm and undisturbed.” In comparison, the state of mind that is revealed and able to respond is referred to as “the mind feeling and communicating.” Cheng Yi, a renowned Confucian scholar, wrote that a “calm and undisturbed state” is the original body of mind, and the state of “mind feeling and communicating” is the operation of mind. He postulated a duality of mind as an a priori state and an experienced state.

-

Since the nature of mind cannot be seen or touched, Confucians viewed it as empty. Buddhists viewed the mind as nothingness. Nevertheless, the mind is not completely empty. The energy of yin and yang is implicitly embedded in the mind. When the mind that has remained calm, it takes an orientation toward something at a given moment, the energy of yin and yang is activated, enabling the mind to feel. This energy allows the mind to realize or embody itself through time and space, and also allows the mind to change into various shapes. Zhu Xi, the founder of Neo-Confucianism in the Song period, compared the nature of the mind to a mirror that is clean and clear, and explained that emotion is something reflected on the mirror of the mind — that is, a reflection of the mind’s mysterious movement. He referred to the change and function of the human mind as “mysterious perception, sensation and judgment”. This mysterious function of mind has two aspects: one is the self-control of trifling emotions and desires generated by the body, and the other is the moral or ethical mind, which is based on human identity. The ethical intelligence refers to a mind that feels shame when it sees something that is not right and detests injustice, a mind of humility and accommodation for other people, and a mind that can discern right from wrong. This mind comes from a place of truth and must be encouraged. This ethical mind provides clues for understanding four personalities: gentle and virtuous, righteous, polite and civil, and wise and sagacious. The mind based on human identity acts as a swinging pendulum, gradually leading us to a state of balanced composure as well as a state of authentic being.

-

Eastern essence-function theory states that the mind would be in a peaceful pause when the body is also paused, and the mind would respond and feel once the body is activated. In other words, states of the mind are understood to match states of the body. This postulation of a mind-body identity is predicated on the theory that both mind and body are subject to the same energies of yin and yang. For this reason, a human being is defined as one and at the same time as two, entailing an argument that a human being can be split in two while maintaining its wholeness. This is the unification of matter and mind. In relation to the tranquility and movement of the mind, Nancy discusses something of note in Corpus. He paraphrased a quotation from Freud that came to light after his death: “the soul is unfolding (étendue) outwards, [but of the movement of being unfolded,] nothing is known.” If we substitute this “soul” for “mind,” we can see that that mind resides peacefully inside and then migrates outward and unfolds itself. The mind is not able to perceive its own movement of expansion because its unfolding is carried out unconsciously and quietly. However, if the unfolded mind makes contact with the body, the body of the mind would move towards the outside and evoke the unification of stillness and movement in the manner of twoness (mind and body) within one (the self) and oneness within twoness. Nancy makes clear that the self’s “unknowing” is the authentic self, and the process of the soul moving toward the outside, registering bodily sensation and going through thoughts and experiences, is the means of the unification of stillness and movement through which the unity of mind and body is exposed to world. Neo-Confucianism long ago explained the phenomenon of the mind being unified with the body (that is its own outside) and expanding toward the world through its essence-function theory.

-

Nothing could illustrate the stillness and then movement of the mind more vividly and persuasively than an experience that came upon Kimsooja one day in 1983, when she was sewing a bedcover with her mother. Suddenly she came to an important realization:

-

Through the banal activity of sewing a bed cover with my mother, I experienced a surprising sensation that my own thoughts, sensitivity and action were all integrated. That unifying sensation was so private and surprising. At that moment, I was able to find some kind of possibility that can include within itself countless memories, pain, as well as affection and love in life, all of which I had buried within me until that moment. The warp and weft as the fabric’s basic structure, the raw sense of colour of our own fabric, the unification of the action of sewing up and through the two-dimensional fabric, the fabric and myself and the strange nostalgia that all of this evoked...with all of this I was completely enchanted.

Later, when describing this experience again, she recounted that when the sharp needle poked into the fabric, she felt the energy of the universe suddenly penetrating through her whole body. This surprising epiphanic experience not only marked the origin of her Sewing series but also helped form the spiritual archetype for her oeuvre. The coincidence of the tension of mind with that of the body in the act of sewing brought memories and emotions that had been buried deep inside the mind to the threshold of the unconscious. This in turn electrified and moved the artist’s body and mind. Kimsooja described how this experience of the unification of her mind and body gave birth to Sewing, in which the meaning of the needle and thread is rooted in oneness of mind and body. Just as mind and body are two sides of a real being, needle and thread are as one and, as a unified entity, do the work of sewing the fabric — which symbolizes the outside world or the infinite space between heaven and earth. In the installation Archive of Mind, the participants are given an opportunity to experience the same kind of epiphany through the ritualistic act of forming clay balls rolled between their hands. -

When one is touched by an artwork, his or her mind is stimulated in response: “the tranquil and unstirred mind” begins to “communicate and stir” in response to the stimulus, thus, revealing itself. In the Sewing series, Kimsooja’s artworks have been structured in a way to best resonate with the stillness and the movement of mind. The bed cover is worked with needle and thread that symbolize the oneness of body and mind. The fabric, smoothly spread out, is a horizontal structure that accommodates the movement of the mind traversing over it. Against the backdrop of the horizontal fabric, the vertical movement of sewing through the warps and wefts represents the unfolding of the mind. The mind, in sync with the hand-movement of sewing, eventually brings to the surface the nature of being and emotion that has been sequestered in the unconscious. It is not just the repetitive hand movement that stirs the stillness of mind; the artist’s mind and body are stimulated on multiple levels. For example, the colorful, traditional fabric Kimsooja uses serves as a strong stimulus for the visual and tactile senses. Furthermore, the artist is inspired by the cultural implications of these silk fabrics. The vertical and horizontal structures in Kimsooja’s work are the most conspicuous visual stimuli that inspire the viewers.

-

...

-

The artist’s working method, which is to join squares of fabric along their widths and lengths and multiply them by sewing, also aligns with the structure of verticality and horizontality. To the question of what Geometry of Mind and Geometry of Body mean, answers may be found if one understands the principles of the three generative forces and the manifestation of heaven, earth, and human. Now let’s delve further into the geometry of the vertical and horizontal structure.

-

As suggested above, the geometry of the vertical and horizontal structure has nothing to do with reifying certain idealistic concepts, nor with the identification and classification of conceptual objects in a geometric lattice. The geometry of the vertical-horizontal structure in this essay refers to a method that helps one intuit the infiniteness of the universe or the intrinsic nature of the uncertainty of being, as well as intuit the state of balance between dualistic, antagonistic elements such as body and mind, or yin and yang. Geometric structuralization is a method to facilitate the observation and reflection of complex, often conceptual, notions. It is necessary to rely on such methods in order to have categorical, systematic or structural unity when contemplating the essence of the indeterminate consciousness called mind. Through this method we are able to reach the intuition of and reflect on such topics as body and mind, or yin and yang, all of which are indefinable by knowledge.

-

In a similar vein, Julia Kristeva, a semiologist, opts for a dualistic system of the semiotic and the symbolic in order to explain how the signification of poetic language is ingenerated from pulsion, which exists under the consciousness. It is, in fact, impossible to formulate the disorderliness and pulsation that flows and moves into a state of segmentation in a self-evident logic or axiom. Nonetheless, Kristeva hypothesizes that pulsion, the drive of desire, generates the ultimate signification of the text. She divides the process of signification into the strata of semiotic and symbolic, and investigates the interaction of these two. Consequently, she claims that signification is ingenerated out of the semiotic field in which the fragmented pulsion is condensed and subsequently connected to the symbolic field in which law, order, and social consciousness are concentrated. In other words, the two conflicting categories are connected in such a way that the semiotic mobility engages with the symbolic order, the former moving into the latter to compose signification.

-

There can be many possible interpretations for the vertical and horizontal structure that characterizes Kimsooja’s work. One would be as follows: (a) the expansion of mind construed as the expansion of the energy of pulsion in the field of the semiotic, (b) the integration of the body with the outside world interpreted as the unification with society and history in the symbolic field, and (c) the monistic dualism of body and mind construed as the formation of signification generated from the cooperation of the semiotic and the symbolic. The mind is the realm that is indefinite and uncertain, like the field of the semiotic. Yet it can be said that the mind’s own expanding energy — that is, the body — creates the meaning of “being” along with the order of the symbolic, such as sewing, the hand movement of rolling clay balls, or the somatic movement of yoga. As for how the pulsion that moves across the artist’s body and mind gives rise to certain meanings in the process of sewing, that is, at the moment of “poking the sharp needle” into the fabric, the artist explained: I experienced a surprising sensation that my own thoughts, sensitivity and action were all integrated. That unifying sensation was so private and surprising. At that moment, I was able to find some kind of possibility that can include within itself countless memories, pain, as well as affection and love in life, all of which I had buried within me until that moment. [...] the strange nostalgia that all of this evoked...with all of this I was completely enchanted.

-

Kimsooja mused that the meaning of her works is forged when subconscious memories and feelings are introduced to the consciousness, causing her to reflect on the innate nature of being. Is this not the true role of art? Art should let the artist’s hidden desires that have been forgotten or hidden in the mundane or everyday to be truly unfolded and expanded onto the horizon of the consciousness, and enable her or him to experience the epiphanic moment of recovering the original emotion and nature of being. It is for this reason that I sincerely recommend viewers immerse themselves and directly participate in the process through which the artist creates the meaning of her art, thereby relishing the opportunity to relive their own memories and feelings as well as intuit the nature of being.

— Extract of Essay from Exhibition Catalogue 'Kimsooja: Archive of Mind' published by National Museum of Modern and Contemporary Art, Korea, 2017. pp.156-269.

A Study on Body, 1981. Silkscreen Print on Paper, 34 x 34 cm. Courtesy of Kimsooja Studio.

A Study on Body, 1981. Silkscreen Print on Paper, 34 x 34 cm. Courtesy of Kimsooja Studio.

몸과 마음의 기하학

서영희 (홍익대학교 미술대학 교수)

2017

-

국립현대미술관은 현대자동차 후원의 ‘현대차 시리즈 2016’을 위한 초대작가로 김수자를 선정했다. 2016년 7월 27일부터 2017년 2월 5일까지, 서울관 제5전시실과 전시마당에 작가의 최근작을 포함한 아홉 점의 작품들을 전시했는데, 출품작들은 평면과 입체, 오브제, 설치 그리고 비디오를 오가는 다양한 매체들로 구성됐다. 그만큼 이번 전시는 작가의 폭넓은 작업 영역과 자유로운 소재 사용을 한 눈에 조망해보는 기회가 됐다.

-

김수자는 국제적인 활동 경력만 해도 거의 30년에 달하는 중진 작가이다. 그런 그가 이번 국내 전시를 통해 한국 관객들에게 보여주려 한 핵심은 어디에 있을까? 전시 때마다 기대를 뛰어넘는 다양한 매체와 설치 방식을 선보였던 그지만, 이번 전

시에서는 그 자신이 설정한 작품 표제와 거기에 담긴 의미에 더 큰 주목을 하게 만든다. 가령 이번에 처음 소개되고 유독 눈길을 끈 두 작품에 각각 ‘마음의 기하학’과 ‘몸의 기하학’이란 제목을 붙여놓았을 뿐 아니라, 다른 전시작에서도 제각각 ‘몸’의

확장 혹은 ‘마음의 확장’으로 해석할 수 있는 가능성을 열어놓았다. 이런 결정 덕분에 전시를 둘러본 사람들은 작가가 이번 기회를 통해 마음과 몸이라는 존재의 이원적 분화를 게시하고자 했음을 직관적으로 파악하게 된다. 우리에게 친숙한 몸과 마음이란 테마를 통해 그리고 두 개념을 확장시킴으로써, 그는 실체와 비실체, 존재의 안과 바깥, 나와 세계 사이의 관계를 사유할 수 있는 장을 펼치려 했다고 생각된다. -

전시의 제목부터 한글로 ‘마음의 기하학’, 영문으로 ‘Archive of Mind’라고 명시된 점만 보더라도, 이 전시가 감각적 매체 사용이나 표현 형식의 소개에 그치지 않고, ‘마음’이라는 관념적 내용을 성찰하도록 유도하고 있다는 사실이 분명해진다. 신중한 관객이라면, 작가의 의도가 예상 밖의 표현 수단이나 형식을 드러내 보여 자신의 현재를 차별화시키는 일에 있지 않음을 간파했을 것이다. 그렇다면 관객들은 관람 내내 무엇을 주목했을까? 아마도 이들은 작품이 어떻게 제작됐는지가 아니고 무엇을 표상하고 있는지를 궁금하게 여겼을 것 같다. 외형적 편차가 큰 이 작품들이 대관절 무엇을 말하고 있는지, 전체 작품들이 가리키는 의미는 무엇이고 작업의 근본 동인은 무엇인지, 또 이번 전시 작품들을 연결해주는 일관된 주제는 무엇인지를 질문했을 것이다. 필자는 이렇게 가정된 물음들에 대한 답변을 찾아가면서 글을 준비하기로 했고, 글의 방향도 이 독창적이고 사색적인 프로젝트가 재연해내는 내용을 풀어보는 쪽으로 맞추었다.

-

지금까지 김수자의 작품을 분석하거나 설명하는 글들을 보면 주로 문화인류학, 심리학, 철학, 종교학, 사회학, 여성학 등의 범주에서 취한 개념들로 풀이하곤 했다. 필자 역시도 그런 참조의 틀을 크게 벗어나지 않을 것이다. 다만 선행한 글들과 다

른 차이가 있다면, 본문에서 논의할 핵심 주제가 그동안 다뤄지지 않았던 ‘몸’과 ‘마음’이라는 점과 작품에서 이것이 각각 어떻게 고려되고 표현이 됐는지, 그리고 두 개념이 어떤 관계인지를 밝히려 한다는 것이다. 이를 위해 필자는 동양의 철학, 종

교적 사유와 서양의 사상을 함께 참조할 것이다. 그리고 논점을 수미일관하게 구축하기보다는, 동서양의 관련 사유들을 작은 단위의 글들로 배열할 것이다. 이어 사유의 각 묶음들이 맥이 잘린 상태로 배치된 가운데, 그 결락된 자리에서 작가의 작품을 이해할 수 있게 하는 사유의 새 국면이 돌출되도록 하는 방식으로 논의를 진행할 것이다. -

몸과 마음, 이원적 일원성

-

‘마음’ 자체를 규명하는 일은 매우 어렵다. 대체로 마음은 사람의 성격이나 품성을 뜻하고, 생각이나 감정을 담아두는 공간을 뜻하기도 한다. 그런데 영어로 마음인 ‘mind’는 머리의 정신, 생각을, 불어로 마음에 상응하는 단어인 ‘âme’는 영혼, 의식을 뜻하는 경향이 있다. 이렇게 한글 ‘마음(心, 心性)’의 뜻과 영어 ‘mind’의 뜻 사이에는 거리가 있다. 이 차이는 동서양의 사유방식의 차이에서 나온다고 여겨진다. 서양에서는 전통적으로 정신과 물질을 이분법으로 나누어 생각해왔다. 정신은 인간의 속성이고 물질은 사물의 속성이라는 것이다. 그래서 사물과 상관없이 저 스스로 사유하는 인간은 정신적 존재로, 물질적 외부 세계와는 무관한 자기 충족적인 실체라고 보았다. 정신의 차원인 마음 역시 물질과 관계없는 자기 완결적 실체여서, 객체인 대상들을 소유하거나 지배하는 주체로 간주되곤 했다. 따라서 정신으로서 마음은 사유하는 이성적 활동의 영역으로, 신체를 포함한 물질계와는 아무 공통점이 없는 차원으로 구획됐다. 이것이 정신과 물질은 아무런 교섭이 없다는 물심(mind and body)이원론의 근거이다. 하지만 동양 사상은 이것과 다르다. 동양에서는 오래전부터 정신과 물질, 영혼과 육체, 마음과

몸의 양자가 서로 분별되면서도 서로에 대해 열려있고 불가분리(不可分離)의 관계에 있다고 생각해왔다. 마음과 몸이 속과 겉처럼 서로 분별되면서도, 지배와 종속의 대립 관계가 아닌 상호보완의 관계에 있다고 보았던 것이다. 동양의 물심일원론, 즉 이원적 일원론은 이렇게 정신과 물질, 마음과 몸이 실체의 표리(表裏, 안과 밖)라는, 즉 서로 떼려야 뗄 수 없는 내외의 일원화된 관점 위에서 확립되었다. 또한 마음과 몸이 궁극에 닿으면, 파열하여 서로 융합하여 하나로 돌아간다고 본다. 이 하나가 우주만유의 근본이자 본래적 시작과 끝이다. 주역에서의 태극, 유학(성리학)에서의 리(理), 불교에서 말하는 일체개공(一切皆空)의 공(空)이 그것이다. -

최근 정신과 물질의 이원론에서 탈피하여 물심일원론에 공명하는 서양 사상가들도 있는데, 그중 한 명이 장-뤽 낭시이다. 낭시는 자신의 책 『코르푸스 Corpus』에서, 그동안 정신에 비해 폄하되었던 몸에 초점을 맞추고, 통상적인 몸과 마음의 불평등한 관계를 재정립하는 시도를 했다.[1] 우선 그가 내세운 전제는 몸이 단독자로서 정신의 지배 아래, 정신에 합병된 그런 몸이 아니란 것이다. 그에 의하면 몸은 밖을 향해 열려 있으며, 밖으로 드러나고 펼쳐지는 몸, 닫히지 않은 몸이다. 흔한 일상 대화에서 영혼이나 정신에 상반된 것으로 떠올리던 몸, 살덩어리로 꽉 차고 닫힌 독자적인 어떤 것으로서의 몸이라는 개념을 부인한 것이다. 낭시가 말하는 몸은 내면의 영혼(âme, psyché, 마음)에 대한 낯선 객체가 아니라, 영혼과 함께 공존하는 상관자이다. 더 정확히 말하면, 몸은 영혼의 확장이고 그것의 겉이며 바깥이다. 우리가 스스로 저 자신이라 생각하던 마음의 밖으로의 확장이 몸인 것이다. 이렇게 확장과 관련된 몸은 외부로 열려있는 존재인 동시에 영혼에 의해 침투되는 것이어서, 몸은 영혼(마음)의 바깥에 있다고 말해진다. 그러면 몸은 보통 저 자신이라 느끼는 영혼에 대한 차이가 되며, 영혼의 타(l’autrui, the other)로서 스스로를 형성하게 된다. 반면에 몸의 대립 쌍으로서의 영혼은 몸에 대해 무엇인가? 영혼 역시 몸에 대해서 차이이고, 타자이며, 몸의 바깥이 될 수밖에 없다. 몸의 바깥 존재가 영혼 혹은 마음이라면, 이 바깥 존재에 의해 몸은 자신의 안을 가지게 된다. 이를테면 몸은 저 스스로인 마음에 대해서 바깥이고, 이를 뒤집을 경우 몸에게 몸의 바깥 존재는 마음인 거다. 그리고 이 바깥 존재에 의해 몸은 자신의 안, 다시 말해 곧 저 자신이 몸이라고 느끼는 영혼을 가지게 된다. 이때 몸의 안 또는 몸의 영혼이란 몸에의 접촉 감각을 이르는 명칭이다.[2] 이렇게 자기 내면성이 외면성과 마주하고 연결되는 것, 이것이 바로 몸과 영혼의 상관성이며, 서로에 대해 안과 밖이 되는 이 상호 공존의 존재 관계를 이 글에서는 몸과 마음의 이원적 일원성의 관계로 간주하는 것이다. 앞에서 필자는 ‘마음’ 자체를 규명하는 일은 매우 어렵다고 썼다.

-

앞에서 필자는 ‘마음’ 자체를 규명하는 일은 매우 어렵다고 썼다. 왜냐하면 마음을 명확히 알 수는 없기 때문이다. 논리로 파악되거나 어떤 경계로 확정 지을 수 없는 것이 마음이니까. 이 앎의 불가능성, 즉 우리 오성(悟性)의 한계를 넘어서는 마음을 통찰하려면, 자기 완결적 주체에 대한 확신을 깨트려야 하고, 닫힌 이기적 자신과의 결렬이라는 경험을 해야 한다. 이어 마음이 밖을 향해 열려 있음을 확인해야만 한다. 마음의 바깥-이것은 마음의 한계이기도 하다-을 무엇으로 부를 수 있을까? 아마도 존재론에서는 몸, 윤리학에서는 타자, 종교철학에서는 자연, 세계, 우주로 부를 것이다. 스스로를 자기 자신으로 느끼는 이 마음이 바깥의 몸 혹은 물질, 자연, 우주로 열리고 펼쳐질(unfolding) 때-낭시가 영혼의 확장이라고 말한 바로 그 과정-, 비로소 우리는 내면으로 끊임없이 함몰되는 주체 중심의 폐쇄성에서 벗어날 수 있다. 에마뉘엘 레비나스(Emmanuel Levinas)와 낭시가 강조했던 저 이타적인 ‘함께-있음’의 공존의 관계도 이런 것이다. 오직 자아만이 주체라는 자기중심적 억견을 넘어 자기 바깥, 즉 몸, 타자, 공동체로 펼쳐지면, 이 외부와의 접촉(le toucher)을 통해, 영혼은 내재성의 한계를 넘어선

다. 그리고 영혼과 육체, 마음과 몸이 ‘함께 있는’ 존재, 즉 ‘복수적 단일 존재(être singulier pluriel)’가 바로 우리의 실체임을 인식하면, 우리는 안과 밖의 동형 구조인 자아와 타자, 자아와 외부세계 내지는 인간과 자연도 본래 같이 나누고 함께 소통하는 관계임을 저절로 자각하게 된다. 필자는 이 복수적 단일 존재 개념을 민주적 공동체 논리로 확대시키기보다, 보편적인 물(

物)과 심(心), 물질과 비물질, 나아가 유한과 무한, 색(色)과 공(空)의 이원적 일원성 개념으로 연결시키고자 한다. -

몸과 영혼의 이원적 일원성 개념을 개진한 낭시가 핵심 논제인 영혼의 확장에서 가장 먼저 불러낸 상대(l’autrui, the other)는 앞에서 말했듯 몸이다. 영혼은 우선 저 자신의 차이자 타자이며, 바깥인 몸에 가 닿으려 한다. 그런데 영혼과 불가분인 이 몸의 전체 피부와 눈, 얼굴은 내부가 아니라 외부를 향해 돌려진 것이다. 눈이 고개를 돌려 저 자신 속의 영혼을 쳐다볼 수는 없다. 그래서 영혼은 이렇게 말할 수밖에 없다: ‘나는 바깥으로부터 나에 닿지, 안으로부터 나를 접촉하는 것이 아니다.’ 바깥을 향한 몸과 접촉하려는 영혼은 이를 위해 에고(ego) 밖으로 나가야 하며, 저 자신의 노출(l’exposition du soi, l’expeausition)인 몸의 피부를 통해 자신과 접촉하게 된다. 몸에 가 닿고 접촉하면 결국 영혼은 마음을 불러일으키게 된다. 영혼의 확장은 이렇게 바깥을 향해, 바깥의 일부로 있는 몸과의 만남으로 구원된다. 에고 밖의 에고, 나와 세계의 경계인 몸 덕분에, 영혼은 주체의 내면으로 기울어짐 없이 균형을 유지할 수 있게 된다. 그래서 평형을 이룬 저울처럼 내면과 몸 양쪽으로 균형을 이루는 영혼과, 주체도 대상도 아닌 채 영혼의 바깥인 몸은 우리의 사유를 새로운 방향으로 접어들게 한다. 김수자 작가의 몸과 마음에 관한 작품들에 대해서도 우리는 이런 논의로부터 해석의 실마리를 발견할 수 있을 것이다.

-

그런데 낭시의 몸과 영혼에 관한 확장적 담론에 대한 참조는 여기서 그쳐야겠다. 그의 이후의 사유가 몸의 실존적 유한성에 대한 논의로 전이되기 때문이다. 사회적 공동체에서 나의 타인을 향한 외존(外存, ex-position)은 어떤 경우에도 지금 여기에 있는 유한한 내 몸과 타인의 유한한 몸이 서로 만나서 이루어지므로, 그렇게 전개가 된다. 하지만 김수자의 ‘몸과 마음의 기하학’ 연작에서는 일상적인 사람들의 유한한 공존 양태가 관건이 아니다. 오히려 초점은 절대 혹은 무한과 마주하는 우리 자신의 본래적 존재 양태에 맞추어져 있다. 그런 점에서 그의 작품은 낭시의 담론을 비켜 나간다. 그리고 존재의 한계인 무한으로 접근하는 경험을 위해, 대부분의 작품들은 몸과 영혼의 이원적 일원성을 상징하는 기하학적 구조와 균형으로 만들어져 있다. 이 기하학적 균형의 추상성은 우리를 직관적으로 또 거의 무의식적으로 절대와 무한으로 다가가게 하는 효과가 있다. 그리고 압도적인 무한 내지 절대에의 접근은 우리를 일상의 평균적인 존재 상태에서 벗어나게 해주는 한편 본래적 실존으로 눈을 돌리게 만든다. 탄생과 죽음 사이에 있는 우리는 보통 존재의 소멸인 죽음을 회피하거나 망각한 채로 살아간다. 하지만 죽음은 엄연히 현존재의 근저에 묻혀 있으며, 가려졌더라도 언젠가는 그것과 반드시 마주치지 않을 수 없다. 그렇다면 존재의 한계인 죽음은 존재자에게 앞으로 닥칠 유일무이한 가능성이자, 존재자에게 본래부터 있던 원천적이고도 고유한 본래성이라고 부를 수 있는 것이다. 요약해서 말하면, 죽음에 이르는 존재가 바로 본래적 존재라는 것이다.

-

이런 존재론적 관점을 처음 피력했던 철학자가 마르틴 하이데거이다. 그는 『존재와 시간 Being and Time』에서 죽음에 이르는 운명의 존재를 본래적 존재라고 불렀다.[3] 그리고 이 같은 존재의 본래성(eigenlichkeit)이 일상의 현존재(dasein)를 본래적 존재인 실존의 존재로 변양시킨다고 하였다. 즉, 유한자인 내가 마음속으로 죽음에 이른다는 것을 미리 예상(anticipation)해둠으로써, 그래서 자신을 죽음을 향해 기투함(던짐)으로써, 죽음-무(無)의 완전한 가능성을 자기 삶 안으로 받아들이게 되고 결국에는 실존의 존재자로서 살아갈 수 있게 된다는 말이다. 일상의 우리는 이렇게 존재자의 예상된 조건인 죽음을 인정함으로서 자기 완결적 에고로부터 탈피할 수 있을뿐더러, 존재자의 가능한 전체 존재-탄생 후부터 죽음 직전까지의 존재-를 확보함으로써 자신의 본래적 가능성 앞에 직면할 단서를 마련할 수도 있는 것이다.

-

그러면 이 ‘죽음에 이르는 본래적 존재’ 개념은 앞에서 말했던 몸과 마음의 이원적 일원성 개념과 상관이 있는가? 필자는 양쪽 개념이 서로 상관있다고 생각한다. 왜냐하면 몸과 마음의 이원적 실체인 인간은 뛰어넘을 수 없는 죽음이라는 저 하나의 절대적 무를 향해 스스로를 열어가는 존재이기 때문이다. 물론 서양 실존주의에서 죽음은 존재의 부정이고 소멸이므로 그 너머를 적극적으로 사유하지 않는다. 현존재가 자신의 죽음을 예상한다 하더라도 죽음의 실현을 위해서 자신의 삶을 추구하는 경우는 없다. 하지만 동양 전통 사상에서는 영육의 죽음을 소멸이 아니라, 존재가 무한한 절대 세계로 들어가는 문턱 내지는 무한과 합치되는 단계라고 생각한다. 그래서 존재의 의미는 오히려 역동적 절대인 태극, 무한한 열림을 뜻하는 공 혹은 무위한 자연의 개념들로 확장이 된다. 그러므로 동서양에서 존재의 본래성을 결정하는 차원이 죽음이든지 아니면 무한한 절대이든지 하는 차이가 있어도, 존재의 완전한 가능성을 개시하는 계기인 죽음 혹은 궁극의 무한이 우리의 존재 의미를 정립한다는 사실을 긍정하는 일은 같다.

-

‘기하학’의 의미

-

몸과 마음의 이원적 일원성에 대한 확인에 이어, ‘몸의 기하학’, ‘마음의 기하학’처럼 작품 제목에 명기돼 있는 ‘기하학’의 의미를 살펴보려 한다. 전시된 작품들 자체가 분명히 입증하고 있듯이, 작가가 의도한 ‘기하학’은 도형이나 공간의 성질을 규명하는 수학 연구도, 원, 삼각형 따위의 도형들을 배열하는 어떤 미술 양식도 아니다. 그의 기하학은 몸 혹은 마음으로 전제된 주제를 수리적 방식이 아닌 직관의 방식으로 시각화해내는 표현 방법에 대한 이름이다. 작가는 이 기하학의 방법으로 다양한 매체들을 사용하며, 관객들로 하여금 몸과 마음, 물질과 의식, 유한성과 무한성, 존재의 본래성과 비본래성 등의 이원적 대립 구조를 환기시킨다. 그리고 기하학적 구조를 통해 각자가 존재의 가능한 양태들을 생각해보도록 이끈다. 이러한 기하학적 표현을 비유해보면, 통계학자들이 많은 양의 복잡한 정보를 도형이나 그래프라는 시각적 모델로 바꾸어 문제를 해결하는 것과 논리학자들이 일반적 원리에 대해 구체적이고 자명한 사실을 논거로 제시함으로써 문제를 연역적으로 확증해내는 방법과 매우 흡사하다. 그만큼 개념적인 표현 방법이다. 때문에 시각예술로서 이미지와 오브제들을 제시하면서도 주관적 감정 표현에 빠져들지 않고, 직관적 인식과 연역법적 개념의 표상으로 공감대를 넓히는 그의 작품은 자연스럽게 개념예술로 분류가 된다.

-

필자는 몸과 마음의 이원적 일원성을 잘 표현해줄 수 있는 기하학적 구조들 중 하나로 수직 수평의 구조를 말하고 싶다. 실제로 1980년대 초부터 현재까지 작가의 작품들은 거의 예외 없이 이 수직 수평의 구조, 즉 수직선과 수평선이 상호 교차해서 균형을 이루는 십자형의 구조를 지니고 있다. 두 상반된 방향으로 진행하는 선들이 만나는 이 구조는 상호 교차하는 접촉점을 중심으로 사방으로 균형을 이루면서 무한하게 펼쳐지는 확장형 운동감을 드러낸다. 안과 밖으로 소통되는 열린 구조인데다, 각도를 돌릴 때마다 방향성이 무한히 변화될 수 있는 구조이다. 또한 수직선과 수평선의 두 선을 직각으로 교차시키는 순간, 4개의 방향이 생기고, 이어 동일한 교차점에서 선들을 두 배수로 거듭 증가를 시키면, 8개, 16개, 32개, 64개… 로 방향을 가리키는 수들이 늘어나게 된다. 동양 전통 종교철학에서는 이 수들을 시, 공간을 암시하는 방향이나 위치로 보아서, 가령 유교의 한 경전인 『주역(周易)』에서는 방향을 가리키는 64가지 기호들인 64괘가 존재의 다양한 속성들을 상징하고, 불교의 태장계 만다라에서는 동서남북의 4부처와 동북 동남서북 서남의 4보살을 각각 담은 8장의 연꽃잎들인 ‘중대팔엽원(中臺八葉

院)’이 중요 도상으로 전래되어 오고 있다. 또한 불교의 법륜(法輪)을 뜻하는 수레바퀴의 8개 내지 16개 바큇살로 온 세상을 가리키는 동시에 이 수레바퀴로 어느 때, 어느 곳이든 굴러가 닿는 부처의 법을, 그리고 천지 사방의 방향에 대한 비유로 어디든 막힘없이 두루 통하는 상태를 뜻하는 화엄종의 ‘원융무애(圓融無碍)’의 원형 이미지가 전해지고 있기도 하다. 이것들은 모두가 본래 음과 양, 하늘과 땅 같은 이원적 구조에서 출발하여, 영원한 시간, 막힘없는 무한 공간의 우주를 상징하는 기하학적 도상들로 전개됐다는 공통점을 보인다. -

한데 『주역』에는 이보다 한 걸음 더 나아가는 ‘천지인삼재’ 개념도 있다.[4] 이 개념은 독특하게 천지의 이원적 체계 위에 세 번째 우주 원리로 인간을 덧붙인다. 우주가 본래 하늘과 땅의 두 근원으로 이루어졌다고는 하지만, 하늘(天)과 땅(地) 사이에 매개체 역할을 하는 인간(人)이 있어야만 비로소 우주의 운행이 제 의미를 띨 수 있다는 개념이다. 세상이 하늘과 땅 사이에 펼쳐져 있다는 천지이원론은 인간(人)의 결여, 즉 인간 부재로 말미암아 ‘마음씀’이 없는 무심(無心)한 자연관이 될 우려가 있다. 그러나 천지자연의 운행에 인간을 참여시킨 삼재론은 인간의 위치를 천지와 같은 수준으로 끌어올릴 뿐만 아니라 천지를 연결하는 중심점이 되게 함으로써, 전통적인 자연관을 인간 중심의 인본주의적 사고로 전환케 한다. 이로써 동양의 자연철학은 인간을 근본으로 하는 윤리학으로 전이되며, 이 후자가 바로 유학이다. 그래서 유학자인 자사(子思)가 저술한 『중용(中庸)』을 보면, 인간이 천지의 화육(化育, 변화와 작용)을 도울 수 있고, 천지의 화육을 능히 도울 수 있어야 인간이 천지와 더불어 삼재가 될 수 있다고 하였다.[5] 이어 인간이 자기를 완성하는 것은 하늘에서 받은 ‘성(性)’을 최대한 발휘하는 것이며,

타자를 돕는 것은 천지의 작용을 돕는 것과 한 가지라고 하였다. 이것이 『중용』이 말하는 명(明, 질서), 즉 인간이 자신을 둘러싼 천지의 질서를 이루는 일이며, 그 실천을 통해서 인간은 세상의 균형과 조화에 참여하는 삼재가 된다는 논리이다. -

그런데 삼재가 되기 위해서는, 인간에게 필히 전제되어야 하는 것이 있다. 바로 실천적 태도라 할 수 있는 윤리적 태도이다. 하늘로부터 부여받은 성(性)-인간에게 있는 성이 하늘의 이치인 리와 동질이라는 성즉리(性卽理)는 유학의 핵심 명제이다-을 따라서, 자신의 몸과 마음을 항상 수양해야만 한다. 몸과 마음에서 일어나는 욕심과 비도덕성을 다스리고 혼탁한 감정을 절제하는 수양을 하면, 중용(中庸, golden mean)의 균형 상태, 즉 어느 한쪽으로 치우치지 않는 평상심으로 정도를 지켜 나아가는 상태에 달하게 된다. 이 중용이 이루어지면 인간은 하늘의 이치대로 자기 본연의 성(性)을 다할 수 있게 되고, 궁극적으로는 하늘과 땅 사이의 무량한 변화에 조응하며 조화를 이루는 주체가 되는 것이다. 그런데 만일 하늘과 땅의 화육을 돕는 매개자인 인간이 부재하거나 혹은 있어도 그런 참여를 하지 않는다면, 세상은 어떻게 될까? 가정해보면, 천지는 각각 독립적으로 분리된 채, 상호 무관한 상태로 머물 고 말 것이다. 하지만 현실에서 인간은 천지와 더불어 삼재가 되는 일이 당연하며, 이 당위성을 토대로 인간은 중용을 실행하려 노력하면서, 천지와 만물을 연결하는 매듭이 되는 것이다. 인간이 마주하는 세상은 앞에서 말한 것처럼 이원적 구조로 정립된 세계이다. 하지만 여기에 인간이 매개자가 되어 개입하면서, 천지(음양)는 서로 어우러져 돌아가게 되고, 이로 말미암아 세계는 이원적 일원성의 실체가 되는 것이다.

-

여기서 거듭 주목해야 할 점은 하늘과 땅의 두 요소가 만나는 균형점이 바로 인간 존재란 사실이다. 비록 그 자신이 유한자일지라도, 인간은 무한한 우주인 수직으로 치솟은 하늘과 수평으로 펼쳐진 땅을 연결하는 잠재적인 접촉점이 된다. 한데 하늘의 기운인 양(陽)과 땅의 기운인 음(陰)이 만나서 이루어지는 존재는 인간만이 아니다. 인간 외에도 삼라만상이라는 만물이 있다. 하지만 천지의 변화와 작용을 도와서 삼재의 우주원리 안에 드는 것은 무심한 만물이 아니라 마음씀이 있는 사람이다. 사람은 천지인의 삼재 가운데서 유일하게 몸과 마음을 가진 존재, 즉 유심(有心)한 존재여서, 무심한 하늘과 땅 그리고 만물을 일원적으로 해석할 수 있는 존재자로 판명된다. 천지의 이치인 리(理)와 동질인 자신의 본성, 즉 성(性)을 충실히 수행하면, 인간은 우주와 합일할 수 있으며, 그 변화에 참여하는 능동적인 주체로 존재할 수 있다. 그래서 자사가 저술한 『중용』에서는 인간이 획득하는 존재론적 차원을 세상 안에서 화합과 일치를 이루는 중화(中和)의 차원이라고 말한다. 이 중화를 다시 인성론의 용어로 바꾸어 말하면 평정 혹은 평정심이다. 인간이 음과 양 사이에서 조화로운 중화에 들면, 몸과 마음이 희로애락에 휩쓸리지 않는 ‘중(中)’의 상태가 되고, 설혹 감정이 일어나더라도 모두 절도에 맞는 ‘화(和)’가 되어, 가장 이상적인 존재 상태가 된다는 것이다. 필자는 이러한 중화가 고대 그리스의 에피쿠로스학파가 추구했던 아타락시아(ataraxia)의 개념과 동일하다고 생각한다. 인간 삶의 행복이 평정하고 안정된 심신의 상태인 아타락시아에 있다고 본 고대 그리스인들과 유사하게 동양 유학자들도 천지의 이치를 따라 심신을 다스리는 중용을 지키면, 불균형이나 치우침 없이 자신의 본성을 인식하는 쾌(快)한 삶을 살 수 있다고 본 것이다.

-

이 글에서 언급한 기하학의 의미 다시 말해 수직 수평 구조의 안정된 균형이 암시하는 내용도 그렇게 유학이 지향하는 존재 상태인 심신의 치우침 없는 평정이 아닐까 한다. 성(性)의 이치에 기초한 심신의 안정된 균형(즉, 중화)을 이미지로 표현할 경우, 이것은 자연스럽게 수직수평 구조의 균형으로 나타날 수 있을 것이다. 물론 작가가 작품을 통해 의도한 내용이 반드시 유학-더 정확히는 성리학-의 명제들과 일치한다고 장담할 수는 없다. 하지만 하이데거가 존재와 무, 삶과 죽음의 이원성을 일원화하여 죽음에 이르는 실존의 존재를 본래적 존재라고 간주한 것 같이, 동양에서도 경험할 수 없는 무한의 절대적 시공간의 이쪽에 있는 인간 삶을 중심으로, 인간의 능동성을 중시하며 존재의 양태를 규명하고자 한 것은 동일하다고 본다. 다만 유학에서는 존재의 본래적 시작과 끝의 원천이라고 생각되는 우주, 즉 천지의 음과 양의 세계에 더 많은 관심을 두었고, 그래서 인간이 천지의 이치(理)와 결부된 성에 큰 비중을 두고 음양의 조화대로 살아가는 균형을 중요시한 고유한 특성이 있다.

-

한편 이번 전시에 처음 소개된 설치 작품인 <마음의 기하학>을 염두에 두고서, 몸과 하나를 이루며 동시에 본연의 성(

性)과도 통하는 ‘마음’을 조금 더 가까이에서 주목해보자. 이 마음은 무엇이라고 규명되기보다도 어떤 상태로 있는 것인가 하고 질문되어야 하리라. 사실 우리의 마음을 스스로 관찰해보면, 이것이 본래는 모양도 없고 움직임도 없는 잠재 상태로 머문다는 사실을 깨닫게 된다. 그러다가 어떤 계기가 생기면, 마음은 비로소 생기는 것 같이 일어나서 지각과 감정을 느끼는 현실

상태로 이동을 하게 된다. 고요한 마음의 잠재 상태가 우리의 시공간을 통과하면서, 겉으로 드러나고 작용하는 현실화된 상태로 전환되는 것이다. 『주역』의 「계사전」에서는 이렇게 아직 밖으로 드러나지 않은 마음 상태를 ‘적연부동(寂然不動, 고요하고 동요하지 않음)’이라 하고, 밖으로 나타나 감응하는 마음 상태를 ‘감이수통(感而遂通, 느끼고 통함)’이라 하였다. 유학자인 정이(程頤)는 이 ‘적연부동’이 마음의 본체(體)이며, ‘감이수통’은 마음의 작용(用)이라 불렀다. 즉, 마음의 상태를

선험적 상태와 경험적 상태로 이원화하는 설명을 한 것이다.[6] -

마음의 본성은 볼 수도 만질 수도 없으므로, 이 심(心)을 허(虛)하다고 말하기도-불교에서는 이를 공(空)이라 함-한다. 하지만 그렇다고 해서 마음이 아무 것도 없이 텅 빈 것은 아니다. 거기에는 음과 양의 기운이 함축돼 있다. 그래서 고요하게 머물던 마음에 어느 순간 대상에의 지향성이 생기면, 마음 속 음양의 기운이 동하여 실제로 느끼고 작용하게 되는 것이다. 이 음양의 에너지는 마음을 시공간을 통해 현실적으로 발현될 수 있게 하고, 또 여러 모양으로 변할 수도 있게 하는 동력이다. 중국 송대에 신유학을 창안한 주희(朱熹)는 마음의 본성인 성(性)을 아직 아무것도 비추지 않은 깨끗하고 맑은 거울로 비유한 한편, 마음이 동하여 작용하는 정(情)을 저 맑은 마음의 거울에 무엇인가 비추어져서 마음이 신묘하게 움직이는 현상이라고 설명했다. 이 같은 마음(心)의 변화와 작용을 요약해서 그는 마음의 ‘허령지각(虛靈知覺)’이라고 불렀다. 그리고 마음이 대상에 대해 작용하는 허령지각은 하나일 뿐이지만, 그 내용은 두 가지여서, 몸에 의해 생겨난 사사로운 감정과 욕망의 허령지각을 절제해야 하는 반면, 마음의 실체인 성(性)을 원리로 한 허령지각은 측은지심(惻隱之心)·수오지심(羞惡之心)·사양지심(辭讓之心)·시비지심(是非之心)의 도덕적 마음씀을 일으키므로 이를 북돋아야 한다고 말했다.[7] 후자의 네 가지 마음씀은 각각

인의예지(仁義禮智)의 실마리가 된다. 마음은 대상을 향한 허령지각을 주재하는 주체이며. 성(고요함)과 정(느끼어 일어남)을 관통하기에 (心統性情), 성을 원리로 한 마음이야말로 우리를 평정의 균형으로 이끌 수 있을 뿐 아니라 존재의 본래적 상태로 향하게 하는 추가 될 수 있다고 하겠다. -

한편 동양에서는 고요히 멈추어 있는 마음을 정지 상태의 몸으로 비유하고, 감응하는 마음을 움직이고 활동하는 몸으로 비유하기도 한다(體用論). 마음의 고요한 정지와 움직임의 양면을 또한 몸의 쉼과 운동으로 간주하기도 하는 것이다. 이처럼 마음과 몸이 동일하게 간주될 수 있는 근거는 둘 다 음양의 기운을 바탕 삼아 정지하거나 움직이기 때문이다. 실체로서 인간이 하나이면서도 둘(몸과 마음)이고, 둘이면서도 하나라는 물심일원론으로 규명하는 것도 그런 연유에서이다. 마음의 정(靜, 고요함)-동(動, 움직임)과 관련하여, 낭시가 『코르푸스』에서 프로이트 사후에 공개된 메모 하나를 인용한 내용은 흥미롭다. 요약하면, ‘영혼은 밖으로 펼쳐진다(étendue, unfolding). 하지만 그 펼쳐짐의 움직임에 대해서는 알지 못한다’는 내용이다.[8] 즉, 영혼을 마음으로 바꾸어 말하면, 안으로 고요히 머물던 마음이 이동해서 밖으로 펼쳐지지만, 이 확장의 움직임을 막상 마음 저 자신은 알지 못한다는 것이다. 왜냐하면 마음의 펼쳐짐은 무의식으로 고요히 진행되므로 그러하다. 하지만 이 펼쳐진 마음이 몸에 닿으면, 마음의 몸은 바깥을 향해 움직이면서, 하나(자아) 속의 둘(심, 신)이자 둘 속의 하나라는 방식으로 일치의 정-동을 일으키게 된다. 즉, 낭시는 이렇게 의식 아래에 있는 자아의 알지-못함[un ne-pas-(pouvoir/vouloir)-se savoir]이야말로 진정한 자아의 본모습일 뿐 아니라, 마음(psyche)이 바깥을 향해 움직이면서 몸의 감각을 동요시켜 사유와 경험을 하게 되는 과정이 세계에 노출되는 심신 일원의 일치된 정-동이라고 밝힌다. 마음이 자신의 바깥인 몸과 하나가 되어 움직이며 세계로 확장되는 일, 이를 두고 신유학은 이미 오래 전에 체용론(體用論)으로 설명했던 것이다.

-

그런데 이 같은 마음의 정-동에 관한 한, 김수자 작가의 오래 전 경험담만큼 생생하고 설득력 있는 설명이 될 수 있는 것도 없다. 이 에피소드는 1983년 어느 날 자신의 모친과 더불어 이불보를 시침하면서, 불현듯 중요한 깨달음을 얻는 순간으로 거슬러 올라간다. “어느 날 어머니와 함께 이불을 꿰매는 일상적인 행위 속에서, 나의 사고와 감수성과 행위가 모두 일치하는 은밀하고도 놀라운 일체감을 체험했다. 그 순간 나는 그 동안 묻어두었던 그 숱한 기억들과 아픔, 삶의 애정까지도 그 안에 내포할 수 있는 가능성을 발견하게 되었다. 천이 갖는 기본구조로서의 날실과 씨실, 우리 천의 원초적인 색감, 평면을 넘나들며 꿰매는 행위와 천과의 자기동일성, 그리고 그것이 불러일으키는 묘한 향수…. 이 모든 것들에 나 자신은 완전 매료되었다”.[9] 또 훗날 작가는 이 경험을 다시 언급하며, 천에 뾰족한 바늘을 꽂는 순간 갑자기 온몸을 관통하는 우주의 에너지를 느꼈다고 회상했다. 이 우연한 경험의 놀라운 일화들은 그의 바느질 연작의 출발점과 전체 작업의 정신적 원형이 무엇인지 분명히 환기시켜준다. 마음의 집중과 몸의 긴장이 일치된 바느질의 순간-<마음의 기하학> 워크숍에서 관객이 두 손으로 흙 공을 굴리는 순간도 마찬가지다-, 마음속 깊이 파묻혀있던 기억과 감정들이 무의식의 경계 밖으로 솟아나 심신이 감동의 전율을 체험하는 것이다. 작가가 이 경험을 바느질 연작의 출발점이라고 고백한다면, 필자는 이 경험이 작가의 마음과 몸의 일치를 노출시킨 최초의 사건이었다고 본다. 그리고 바늘과 실의 의미가 바로 이 심신 일원의 확장 개념에 뿌리내리고 있다고 생각한다. 마음과 몸이 실체적 존재의 양면이면서도 바깥세계에 대해서는 하나이듯이, 바늘과 실도 서로 연결된 채 하나가 되어 바깥세계 혹은 천지간의 무한 공간을 뜻하는 천들을 꿰매어 나간 것이다.

-

작품에 대한 감동은 현상적으로 가만히 있던 마음이 동요하여 움직이기 때문이다. 다시 말해 적연부동의 고요한 마음이 어떤 일을 마주하게 됐을 때, 그에 반응하여 감정이 통하고 움직이는 감이수통으로 바뀌기 때문이다. 특히 바느질 연작의 경우, 이러한 마음의 정(靜)과 동(動)의 구조가 매우 확연하게 드러난 편이다. 몸과 마음의 일원성을 상징하는 바늘과 실이 마주하는 이불보, 이 평평하게 펼쳐진 천은 그 위에서 전개될 마음의 움직임을 수용하는 물적 토대이자 수평의 구조이다. 그리고 천의 씨실과 날실 사이를 위 아래로 넘나드는 바느질은 수직 구조의 운동으로 마음의 펼쳐짐 내지 확산 작용을 불러일으키는 전제가 된다. 이렇게 바느질의 손동작에 감응하면서 마음은 급기야 무의식 아래 은폐됐던 존재의 본성과 감정을 의식의 지면 위로 떠올리는 것 이다. 물론 반복된 손동작만이 고요하던 마음을 동요시키는 유일한 계기가 아니다. 작가의 심신은 복합적으로 자극을 받는다. 가령 오방색 이불보의 광택, 색, 질감에 의해 시각과 촉각의 감각이 자극될 뿐 아니라, 오방색 비단 천의 전통적, 문화적 함의에 의해서도 자극을 받는다. 결국 이 모든 마음의 복합적인 변화 과정을 기하학적 이미지로 표현한다면, 그것은 수직 수평 구조의 이미지가 될 수밖에 없다.

-

작가가 1980년대 중후반에 바느질 연작의 제목으로 선택했던 ‘ㄱ, ㄴ, ㄷ, ㄹ’도 역시 수직선과 수평선이 결합된 구조를 보인다. ‘ㄱ, ㄴ, ㄷ, ㄹ’은 한글의 17개 자음자들 중 첫 네 가지 기호들이다. 15세기에 한글을 창안한 학자들은 훈민정음 제자(制字)의 합리적 체계를 위해, 『주역』의 질서정연한 음양오행의 원리와 천지인삼재의 모양을 본뜨는 상형의 원리를 따랐다. 가령 네 기본 자음자들인 ‘ㄱ, ㄴ, ㄷ, ㄹ’은 소우주로 여겨지는 사람의 몸, 그 중에도 발음기관인 혀가 각 기호를 발음할 때의 모양을 본뜬 것이며, 세 기본 모음자들인 ‘•, ㅡ, ㅣ’는 ‘천, 지, 인(하늘, 땅, 사람)’의 모양을 본뜬 상형 원리로 만들어졌다. 그래서 하늘의 형상으로 둥근 점을, 땅의 형상으로 평평한 수평선을, 사람의 형상으로 서있는 수직선을 모음 형태로 삼았고, 음양의 원리대로 하늘-‘•’은 양기(陽氣)를, 땅-‘ㅡ’은 음기(陰氣)를 그리고 사람-‘ㅣ’은 천과 지, 음과 양을 잇는 중성(中性)의 기운을 의미한다고 보았다. 또 한글에서는 자음과 모음이 결합된 글자가 완벽한 기하학 형태인 정사각형의 공간 안에 맞추어지는데, 그 안에서 자음, 모음의 배열은 하늘을 뜻하는 초성, 사람을 뜻하는 중성 그리고 땅을 뜻하는 종성의 순서로 구성이 된다.[10] 이처럼 인간을 중심으로 하늘과 땅의 배열과 음양의 질서를 따르는 한글 제자의 원칙과 동일하게, 바느질 연작에서도 하늘

과 땅, 물(物)과 심(心), 음과 양의 관계를 보여주는 수직 수평의 구조적 원리가 작용한다. 작가가 자신의 첫 작품들-바느질 연작은 그의 데뷔작임-에서 보여준 제작방식, 즉 바느질로 사각형 천들을 가로와 세로로 연결하며 확장해나가는 방식은 가장 최근작들인 ‘마음의 기하학’과 ‘몸의 기하학’이 암시하는 확장적 조형질서, 즉 수직 수평의 기하학적 구조와 그 의미를 이해하는데 매우 유효한 도움이 된다. -

우주 혹은 세계는 본질적으로 확장적이다. 워낙 광대하고 무한해서, 유한한 존재인 인간에게는 절대적인 미지의 타자로 간주된다. 그러면서도 인간 생명의 시작과 끝의 원천인 우주는 인간을 비롯한 만물의 생성과 변화 그리고 소멸을 포용하는 공간이기도 하다. 또한 소우주로 비유되는 인간의 몸과 마음의 작용도 객관의 논리로 설명되거나 질서정연한 체계로 규명될 수 없다. 그러면 이러한 세계와 인간 전체를 수 직 수평의 구조 같은 하나의 단일한 체계 안에 가두어 놓기가 가능한 일일까? 상식적으로 생각할 때, 그것은 불가능한 일이다. 따라서 필자는 김수자의 작품론에서 수직 수평의 기하학적 구조가 왜 필요한지에 대해 짧게 해명해보려 한다.

-

앞글에서 암시했듯이, 수직 수평의 구조라는 기하학은 어떤 이상적 관념을 구체화해서 부동의 사유로 포획하거나 그것을 물신화(fetishize)하는 일이 아니다. 또 객관적 질서로든 ‘나’의 자기동일성을 위해서든 대상을 위계화하거나 대상의 차이를 사라지게 만드는 그런 일도 아니다. 필자가 이 글에서 말하는 수직 수평의 기하학적 구조는 우주의 무한성에 대해 혹은 불확실한 존재의 본래성에 대해 직관하는 방식이자, 몸과 마음, 음과 양 같은 이원적 대립의 요소들을 배타적이 아닌, 즉 다양성을 포용하는 일원화된 관계, 균형의 상태로 직관하기 위한 방식이다. 구조화, 체계화는 그 같은 대상에 대한 관찰과 관조를 가능하게 하는 여건이다. 마음이라는 불확실한 의식의 본질을 관조하는 데는 그에 유효한 통일성, 즉 체계나 구조의 범주가 필요할 수밖에 없다. 그래야지 몸과 마음, 타자로서의 우주, 음과 양 등 지식으로 확정지을 수 없는 주제에 대해 직관과 성찰의 시선이 도달할 수 있는 것이다.

비유하자면, 기호학자인 줄리아 크리스테바(Julia Kristeva)가 의식 아래의 욕동(pulsion)에서부터 시적 언어의 의미가 산출되는 과정을 직관하기 위해, 세미오틱(sémiotique)과 생볼릭(symbolique)의 이원적 체계를 선택한 일과 흡사하다. 분절 상태로 흐르고 움직이는 욕동의 무질서와 유동성을 공리화하는 일은 사실 불가능하다. 하지만 크리스테바는 욕망(desire)의 맥동인 욕동(pulsion)이 텍스트의 최종적 의미의 근원이 된다는 전제 아래, 의미 생성의 과정(le procès de la signifiance)을 세미오틱과 생볼릭의 두 층위로 나누고, 이들 두 층위가 어떻게 상호작용하는지를 연구하였다. 그리하여 궁극적으로 의미 생성은 분절된 욕동의 세계를 압축(condensation/verdichtung)한 세미오틱과 법, 질서, 사회적 의식을 압축한 생볼릭이라는 두 대립적 범주들이 서로 연결됨으로써, 즉 세미오틱의 운동성이 생볼릭의 질서에 개입하고 그 속으로 이동(deplacement/verschiebung)하게 됨으로서 의미가 결정된다고 본 것이다.[11]

-

만일 김수자 작품의 수직 수평 구조에 대한 범주화의 모든 다양성을 받아들인다면, 마음의 확장을 세미오틱의 욕동 에너지의 확장으로, 몸의 바깥세계와의 결부를 생볼릭의 사회, 역사와의 결부로 비교하는 일이 그리고 몸과 마음의 이원적 일원성을 세미오틱과 생볼릭의 두 층위가 함께 의미생성을 하는 과정으로 비유하는 일이 가능할 것이다. 마음은 세미오틱의 범주처럼 불확실하고 확정지을 수 없는 영역이지만, 그 기운(에너지)의 확장은 몸 예컨대 바느질이나 흙을 굴리는 손동작, 요가의 몸동작 같은 생볼릭의 질서와 함께 존재의 의미를 만들어낸다고 볼 수 있다. 몸과 마음을 가로지르는 욕동이 바느질의 순간, 즉 천 위에 ‘뾰족한 바늘을 꽂는 순간’에 어떤 의미를 발생케 하는지를 작가는 이렇게 설명했다. “나의 사고와 감수성과 행위가 모두 일치하는 은밀하고도 놀라운 일체감을 체험했으며, 묻어두었던 그 숱한 기억들과 아픔, 삶의 애정까지도 그 안에 내포할 수 있는 가능성을 발견하게 되었다, 그것이 불러일으키는 묘한 향수…. 이 모든 것들에 나 자신은 완전 매료되었다”. 이처럼 의식 밑에 묻혔던 기억과 감정이 의식 밖으로 표출되면서 그리하여 존재의 본래성을 관조하면서, 작품의 의미는 산출이 된다. 진정한 예술작품은 이와 같지 않을까? 일상에서 잊히고 은폐됐던 욕망이 의식의 지평 위에서 실제로 펼쳐지고 확장되는 일, 그래서 존재의 본래적 감정과 본성의 귀환을 환영하는 그런 소중한 기회가 아닌가 한다. 그러므로 필자는 관객들이 작가의 작품을 통해 욕망과 감수성이 의미를 생성하는 과정에 몰입하거나 가능하다면 그 과정에 직접 참여해보도록, 그래서 몸과 마음의 일치로 자신의 기억과 감정을 되살리고 존재의 본성을 직관해보는 기회를 누리도록 진심으로 권유하고 싶다.

-

<마음의 기하학>

-

몸과 마음에 대해서 말하거나 표현하는 것은 어떤 열려 있고 무한한 대상에 관해 이야기하는 일과 같다. 이러한 경우에 작품에 대한 실증적 사고는 전혀 적합하지 않다. 총괄적 단일화를 요구하는 형식주의 관점도 부적합하다. 몸과 마음에 대한 담론은 이것이 무엇이라고 단정적으로 말하는 일이어서는 안 된다. 결정 불가능한 주제가 직관의 대상이 될 수 있도록, 그것이 어떻게 펼쳐지고 드러나는지를 말하는 일이어야 한다. 특히 마음은 몸과 달리 모양도 없으며 분할도 가능하지 않다. 다만 잠재성의 상태로 일정한 질(quality)만을 가진다. 그러면서 마음은 계속해서 일어나고 작용하는, 즉 지속적으로 차이를 일으키며 분화를 이룬다. 수직 수평의 기하학적 구조가 필요한 이유도 이런 불확정성 때문이다. 기하학적 구조가 그런 마음의 작용을 연역적으로 직관하게 하는 방법이 될 수 있기 때문이다. 그런데 이 기하학적 구조가 마음을 연역적으로 추론하는 방식일 수는 있어도, 마음을 완벽하게 도해하거나 설명해내는 해결책은 아니다. 그럼에도 해명하지 못함이 그의 작품을 이해하고 감상하는 일을 저해하지는 않는다. 왜냐면 마음은 본래 설명되고 증명되는 것이 아니기 때문이다. 이런 생각으로 필자는 작가의 최근작인 <마음의 기하학>을 살펴보고, 마음의 작용을 둘러싼 작품의 의미를 밝혀보고자 한다.

-

일반적으로 작품은 작가가 완성한 다음에 전시장에 설치된다. 이것이 작품 전시의 관례이다. 하지만 <마음의 기하학>은 작가의 기획대로 전시장에 설치된 다음, 관객이 작품을 점차 완성해 나간다. 작가가 작품의 일부를 설치했다면, 관객이 작품의 다른 부분을 완성하는 것이다. 작품은 참여하는 관객에 의해 매일 진행되며, 작품의 의미도 전시 기간 동안 계속 생성 중에 있다고 보아야 한다. 가령 관객은 전시장 입구에서 제공된 찰흙을 두 손바닥으로 굴려서 작은 구를 만들며, 완성 후에는

이 구를 커다란 테이블 위에 올려놓는 행위를 한다. 관객이 스스로 흙 공을 만드는 이 작업은 작품의 형태와 의미를 결정하는 매우 중요한 과정이다. 그래서 이 작품을 관객이 참여해서 완성하는 워크숍이라 부르기도 한다. 한편 관객들이 빚어놓은 흙 공들은 어느 정도 건조가 되면, 정기적으로 테이블 중앙으로 모아지고 촘촘하게 디스플레이 된다. 마른 흙 공들이 테이블 중앙에 모여 있는 장면은 천정의 카메라로 촬영되어, 다른 전시실 벽면에 부착된 TV모니터에 실시간으로 그 영상이 비추어진다. 완성된 흙 공들은 하루 종일 테이블 위에 놓여 있지만, 이후 일정 분량이 되면 저장고로 옮겨진다. 그래서 테이블 위에는 다음 관객들이 흙 공을 만들어 놓을 빈 공간이 늘 확보되어 있다. -

<마음의 기하학>에서 돋보이는 소재들은 커다란 테이블과 그 위에 올려져 있는 흙 공들이다. 전시장에 들어서자마자 보게 되는 길이 19m, 폭 11m에 달하는 타원형의 목조 테이블 덕분에, <마음의 기하학>은 이번 초대전에 소개된 작품들 중 규모가 가장 큰 설치 작품이 됐다. 테이블 위에는 이미 완성된 흙 공들이 펼쳐져 있어서, 금방 입장한 관객들의 시선을 수평으로 확산시킨다. 작품을 구성하는 핵심 요소는 테이블 위에 세워져 있는 작고 둥근 흙 공들이다. 관객들이 이것을 만들기 위해 각자 손바닥으로 흙덩이를 굴리며 고요히 명상에 잠겨있는 모습은 쉽게 잊히지 않을 만큼 인상적이다. 그들이 흙 공을 만드는 과정에 충분히 몰입할 수 있도록, 전시장 조명은 다소 어둡게 설정되어 있다. 천정에서 수직으로 내려오는 빛이 수평으로 펼쳐진 테이블 표면을 환히 밝힐 뿐, 다른 조명은 없다. 관객들을 위한 36개의 의자도 대략 1m 이상의 넉넉한 간격으로 설치되어, 누구든지 익명의 상태로 조용히 흙을 빚고 내면화되는 경험을 하게 된다. 작가는 이것을 관객이 자신의 마음을 흙 공에 담아내는 일 혹은 자신의 마음의 보따리를 싸는 일이라고 비유했다.

-

관객이 자신이 빚고 있는 흙 공에 마음을 투사하는 과정은 비정형의 흙덩이가 차츰 둥근 구형으로 변형되는 과정과 일치한다. 그리고 알 수 없는 마음의 상태는 몸의 두 손 혹은 흙을 굴리는 손바닥의 감각으로 확장됐다가 이어 형태가 없는 흙덩이가 점차 구형으로 변화되는 과정을 통해 세계와 맞닿는 경험을 하게 된다. 두 손바닥으로 흙을 감싸 굴리면서 서서히 완벽한 구형의 오브제를 만드는 행위는 실상 어떤 목적도 염두에 두지 않는 무위의 신체행위이다. 하지만 이 무위의 반복 행위를 통해서, 관객은 자연스럽게 자신의 내면으로 집중하게 된다. 이어 자신의 내면-마음을 관조하면서, 보이지 않는 마음의 본래적 고요함을 인식하는 한편 그런 마음을 움직여서 구체적 실재인 흙 공으로 이환해내게 된다. 그러니까 두 손을 비비면서 둥근 구를 만드는 과정은, 불교에서 수식관(數息觀)을 행할 때, 숨을 다듬고 생각을 가라앉혀서 마음을 정관(靜觀)하는 과정과 다름이 없다. 또 잠재상태의 마음을 바깥으로 분화해내는 과정이기도 하고, 모난 마음을 다듬어 바로잡는 자기수양의 과정이기도 하다. 어느 쪽이든, 둥근 흙 공을 만드는 과정은 가능태로 잠재된 마음을 직관하는 일이며, 더 나아가서는 마음을 다스

리는 수양의 윤리적 의미까지도 실현하는 일이라고 볼 수 있다. 작가는 이렇게 관객이 자신의 마음에서 출발해 기하학적 형태의 구를 빚어내는 일에 주목하여, 이 작품을 ‘마음의 기하학’이라고 명명하고, 또한 각자의 마음을 표상하는 흙 공들이 테이블 위에 쌓이기 때문에, ‘Archive of Mind’란 영문제목을 붙였다고 생각된다. -

테이블과 그 위에 올려져 있는 흙 공들의 이원적 관계를 생각해보자. 수평으로 펼쳐진 테이블과 그 위에 세워진 흙 공들은 작가의 선행 연작들이 보여준 이원적 구조의 연장선상에 있다. 가로와 세로로 연결된 천들을 제시한 <바느질> 연작이나 평평한 장소에 우뚝 세워놓은 <보따리> 연작, 그리고 지구 곳곳의 지면을 밟고 꼿꼿이 서있는 <바늘 여인> 연작, 들숨과 날숨으로 교차되는 <호흡> 연작, 하늘과 땅 사이의 자연 풍경과 씨실과 날실이 직조되는 광경을 보여주는 <실의 궤적> 연작은 경이롭게도 모두 수직 수평의 이원적 구조 내지는 그와 동등한 이원적 질서의 세계를 보여준다. <마음의 기하학>에도 수평의 테이블과 수직으로 서있는 흙 공들 사이의 물리적인 이원적 관계가 있다. 나아가 작품의 의미가 발생되는 측면에서 이원적 일원성의 관계를 주목할 수도 있다. 가령 마음과 흙 공 사이의 의미 생성 관계가 그렇다.

-

마치 보따리 연작에서 보따리를 쌌다가 풀어 펼치고, 다시 싸고 푸는 과정을 반복하면서, 보따리의 의미가 생성되듯이, <마음의 기하학>에서도 마음과 몸 그리고 흙 공으로 이어지는 확장적 펼침이 무수히 반복되면서 작품의 의미가 형성된다. 마음과 흙 공의 관념적 위상은 각각 무형과 유형, 잠재태와 현실태, 가능태와 실제태, 공(空)과 색(色), 무(無)와 물질이다. 하지만 작품의 진행 과정에서 이들 이원적 대립의 쌍들이 차츰 일원적 일치를 이루면서, 작품의 의미의 깊이는 생성되는 것이다. 관객이 자신의 흙 공을 빚어내는 과정은 그의 텅 비어있던 마음이 일어나고 생겨남을 사유하고 경험하는 허령지각의 과정이며, 자신의 무형의 마음을 유형의 물질로 변화시키는 과정이다. 다시 말해 잠재태의 공(空)한 마음이 현실의 흙 공이란 실제 상태로 분화되어 나오는 과정이다. 동시에 비정형의 흙덩이가 자신의 두 손안에서 흙 공으로 변화되는 과정을 관조하거나 혹은 테이블 위에 세워진 흙 공을 관조하는 관객은 유형의 물질을 계기로 그로부터 자기 몰입을 하면서 내면화되는 경험을 하게 된다. 필자는 이 과정을 물질에서 자아를 찾는 일 혹은 정반대로 물질에 집착하는 자아를 비워서 무아(無我)의 단계로 건너가는 일이라고 생각한다. 특히 후자를 불교에서는 색에서 공으로 건너가는 의식 과정이라고 말하며, 도교에서는 작위에서 무위로 전환되는 의식 과정이라고 말한다. 비유하자면 묵주로 기도하는 신자들이 묵주의 작고 둥근 공들을 굴리면서 자신의 마음을 비우고 무아의 단계로 이입되는 일과 같다. 또한 관객이 자신의 마주한 두 손바닥과 그 가운데 흙 공이라는 양 극점 사이에서 힘의 균형을 지각하면서, 자연스럽게 마음의 본래 상태 내지 무위 상태로 들어가 고요한 평정을 발견하는, 즉 다시 말해 심신이 하나가 되는 입정(入靜)을 하는 일과도 동일하다고 본다. 결국 작품의 의미는 이 같은 이원적 일원화 과정(1+1=1)을 통해서 형성되며, 이 일원화를 위해 이원적 위상이 상호 지향적이고 확장적이라는 것은 필요불가결한 조건이 된다고 하겠다.

-

<마음의 기하학>에서 이원적 일원성을 발견하게 되는 또 다른 계기가 바로 우리의 공감각 작용, 즉 감각들 사이의 접촉에 있다. <마음의 기하학>은 관객들이 차분한 관조 상태에 이입되도록 하기 위해 세 가지 감각적 통로를 제시한다. 테이블 위에 세워진 흙 공들을 바라보는 시각 경험과 손바닥으로 흙덩이를 굴리는 촉각 경험 그리고 어두운 조명 아래에서 물 흐르는 소리를 듣는 청각 경험이 그것이다. 물 흐르는 소리의 내용을 더 정확히 말하면, 그것은 작가가 입안에서 가글링하는 소리,

즉 물방울들이 뒹굴고 부딪히는 소리와 그 외 자연 상태에서 물방울들이 떨어지고 구르고 흐르는 소리다. 작가는 이들 총 36가지의 소리들을 15분 31초의 길이로 녹음하여 테이블 아래에 장착한 스피커로 들려준다. 이것이 <마음의 기하학>과 함께 최초로 공개되는 <구의 궤적>이라는 사운드 퍼포먼스 작품이다. 필자는 테이블과 흙 공들로 구성된 설치작품에서 경험하는 시각 촉각의 내용과 <구의 궤적>에서 경험하는 청각의 내용이 상호 교차하면서 감각들 간의 공명 상태를 이룩하는 것을 높이 평가하고 싶다. 낭시가 말한 것처럼, 마음의 확장인 몸을 이미지로 덧씌워 표현하지 않으면서, 실제 우리의 몸을 그대로 쓰는 것이 공감각 작용이다. 이 공감각은 마음과 몸의 간격을 가로지르는 작용일 뿐 아니라, 감각들 간의 접촉으로 인해 실존의 확장을 일으키며 바깥으로 펼쳐지는 ‘몸-쓰기(l’excription du corps)’가 되기도 한다.[12] 그리고 감각들 간의 적극적인 상호 교차적 감각작용은 사유를 촉발시켜, 심신의 동일한 역학적 움직임, 즉 일치하는 움직임을 돌아보게 한다. 테이블 위의 작고 둥근 흙 공의 형태와 사운드가 상기시키는 물방울의 형태는 그것들의 근본적인 물성의 차이에도 불구하고, 둘 다 기하학적으로 완벽한 구형이라는 공통점으로 연결되어 있다. 공감각 작용이 그만큼 쉽게 이루어질 수 있는 조건을 갖춘 셈이다. 다만 차이가 있다면, 흙 공은 마음이 구체적으로 물화된 시각 촉각의 이미지인데 비해, 물방울의 사운드는 마음을 추상적으로 상기시키는 청각 이미지란 점이다. 또한 흙 공은 부동 상태로 멈추어 있어서 마음의 잠재적 운동성을, 뒹구는 물방울 소리는 마음의 실제화된 운동성을 유추하게 한다. 그럼에도 불구하고 공감각의 역동성은 마음과 그것의 확장인 몸의 동역학성과 연동성을 암시하는 최적의 표현임이 분명하다. -

거대한 타원형 테이블 위에 밀집된 채 모여 있는 흙 공들은 우주의 타원형 궤도를 따라 늘어선 행성들의 배열처럼 비추어져서, 테이블의 수평면은 은하계의 별들을 보여주는 스크린처럼 지각되기도 한다.[13] 흙 공의 기하학적 형태인 구가 공간에서 물리적으로 작용하는 중력, 인력 같은 구심력의 상징적 형상임을 의식한다면, 또한 천정에 고정된 카메라로 촬영된 테이블 위의 스펙터클 영상을 볼 때, 색도 크기도 조금씩 다른 수많은 흙 공들의 배열 장면이 구심력을 유지하는 소우주 같아

보인다는 점을 상기하면, 마음의 압축, 마음의 보따리를 뜻하는 흙 공의 본래적 의미에 좀 더 가까이 접근할 수가 있다. 그런데 생각해보면, 이 마음의 보따리는 영구적으로 고정되어서는 안 되고, 반대로 풀려서 밖으로 펼쳐져야만 한다. 사실 보따리는 그 본래 의미대로라면 이산형 (dispersion)의 오브제이다. <구의 궤적>, 즉 ‘Unfolding sphere’의 음향은 물방울이 흐르고 구르고 뒹굴며 확산되는 운동을 하고 있음을 명백히 가리킨다. 그러니까 마음의 기하학적 형태인 구가 이번에는 우주 혹은 세계가 얼마나 리드미컬하고 팽창적인지, 또 마음의 이동도 결코 멈추지 않을뿐더러 항상 잠재적 운동 상태에 있다는 것을 가리키는 기호가 되는 셈이다. -

<마음의 기하학>과 <구의 궤적>에서 각각 지각되는 내용의 차이는 자극을 수용하는 감각기관-눈, 손, 귀-이 달라서라기 보다도, 시각, 촉각이 공간 감각인 반면 청각은 시간 감각이란 차이에서 비롯된다고 하겠다. 하지만 그럼에도 불구하고 두 작품은 상호 배타적이지도 않고 대립적이지도 않다. 오히려 작품의 감각인상들은 상호 보완적이며, 서로를 향한 감각전이(sense transference)를 통해, 작품의 의미에 대한 관객의 교감을 증폭시키는 효과를 낳는다. 전자가 후자를 시각 촉각적으로 해석한 작품이라면, 후자는 전자를 청각적으로 해석한 사례이다. 흙 공들이 테이블 위에서 구르다가 멈추어 선 스펙터클을 <구의 궤적>은 소리를 통해 물방울의 끝없는 펼침의 운동으로 전환시켜 놓았다. 멈춤과 움직임, 고요함과 소리, 압축과 팽창, 접음과 펼침 등의 이원적 대립 요소들은 서로에 대한 보완으로 작용하고 또 상호 조응하면서, 결국 지각 효과를 상승시키고 주제인 마음의 의미를 다층적으로 나타낼 수 있게 한다고 본다. 관객의 입장에서도 여러 동시감각의 통로를 따라 작품의 깊이를 다층적으로 관조할 수 있는 여건을 갖는 셈이다. 문학적 기법으로 치자면, 감각의 전이와 결합은 환유와 은유의 형식이다. 공감각으로 인해 그만큼 작품의 의미화(signification) 형식은 더 다양해졌으며, 관객이 작품의 주제와 그 내용의 깊이에 접근할 수 있는 가능성도 더 커졌다고 할 수 있다.

-

<마음의 기하학>에서 드러난 수직 수평의 이원적 구조와 그것이 형성하는 의미를 살펴보면, 성리학의 심론(心論)이 마음의 생성을 설명하는 방식과 유사하다는 생각을 배제할 수 없다. 일단 수평의 타원형 테이블과 그 위에 서있는 구형의 흙 공들은 특정 대상과의 구체적인 유사성(similitude)이 없다는 점에서 초형태적이다. 이 오브제들은 현실의 어떤 대상의 생김새를 모방하거나 재현한 것이 아니다. 구체적인 지시대상(referent) 없이, 엄밀하게 기하학적인 형태로 현시된 이 오브제들은 수직 수평의 구조를 통해서 의미를 산출하는 관념적이고 상징적인 기호들이다. 일반적으로 언어학, 기호학 그리고 우주론(cosmogony) 내의 생성론에서는 무한과 유한, 불변과 변화, 부동과 유동이 서로 연동하는 이원적 대립쌍의 개념들이라고 이해한다. 앞에서 언급한 동양의 『주역』에서도 마찬가지이다. 음과 양의 대립적인 두 기운이 연결된 채, 우주의 보이지 않는 에너지로 잠재해 있고, 마음 역시 이 한 쌍의 기운들에 의해 생겨나거나 소멸한다고 기술하고 있다. 본래적 마음 상태-공(空)과 허(虛), 무(無)의 상태-에서는 음과 양의 에너지가 부동이고 불변이어도, 마음은 언젠가 일어나고 변화하기 마련이므로, 마음의 본성은 항상 음과 양의 에너지로 연동될 수 있는 가능태 (dynamis)-아리스토텔레스, 들뢰즈(Gilles Deleuze)가 사용한 개념로존재한다고 간주된다. 그러다가 계기를 만나면, 잠재된 에너지가 가능태에서 현실태(actuality)로 전이되어, 현실 속 실재로 변화된다고 보는 것이다. 이처럼 에너지가 잠재태에서 현실태로 혹은 가능태에서 실재태로 전이됨으로서, 우주 만물이 생성된다는 대개념은 동서양에서 우주와 사물의 생성을 설명할 때 보편적으로 적용이 된다. 존재론에서 주체의 형성을 설명할 때나 기호학에서 의미의 생성(le proces de la signifiance)을 설명할 때도, 역시 이 개념은 적용된다.

-

마찬가지로 성리학에서도, 음과 양의 기운을 지닌 마음은 존재의 정지된 근원이 아니라 인식과 지각의 능동적인 주체로서 고려된다. 심지어 마음은 우주의 이치인 리(理)와 연결되어 있어서, 마음의 성즉리(性卽理)의 원리로 온갖 윤리적 판단 및 감정과도 통한다고 여겨진다. (心統性情). 하지만 본래적 마음은 부동이고 불변이어서 고요하고 공허(虛)하기만 하다. 그러다가 타자와의 관계 내지는 사물과의 접촉이 생기면, 마음은 현실적으로 생겨나고 작용하며, 지각하고 변화한다. 가령 <바느질> 연작에서 실과 바늘이 천을 뚫고 움직이니까 마음이 감응하는 것이고, <마음의 기하학>에서도 두 손으로 흙을 만지며 비비니까, 그 접촉으로 인해 마음이 일어나고 작용하는 이치이다. 이런 관점으로 마음을 살피기 때문에, 성리학에서는 마음의 정동(靜動)을 매우 중시하여 설명하는 경향이 있다. 즉, 마음이 고요함에서 일어난다거나, 잠잠함에서 동함으로 변화하는 현상을 주목하는 것이다. 그런 맥락에서 주희와 퇴계 이황은 ‘적연부동 감이수통(寂然不動 感而遂通, 고요히 움직이지 않다가, 느껴서 통하다)’이라는 『주역』의 「계사전」의 문구를 빌려서 마음의 부동과 동을 해설했다. 그리고 마음이 사단칠정(四端七情)[14]을 발할 때, 이 마음의 작용을 잘 통제하여 존재의 본성과 본래적 감정을 놓치지 말도록 권유한다. 작품이 수직 수평의 기하학의 구조로 마음의 균형을 포착하려는 의도도 이렇게 존재의 본래적 상태를 파악하기 위함이라고 할 수 있지 않을까…. 필자는 작가가 <마음의 기하학>에서 궁극적으로 산출하려는 의미가 바로 여기에 있다고 확신한다.

-

<몸의 기하학>

-

<몸의 기하학>은 작가가 2006년부터 2015년까지 거의 10년 동안 매일 사용했던 요가 매트를 오브제로 사용한 평면 작품이다. 이 짙은 적갈색의 평범한 요가 매트 위에는 일반 회화에서 기대할 수 있는 것과 달리, 아무런 형상도 붓질 자국도 없다. 단지 오랜 신체 접촉으로 인해 생긴 자국들이 천이 마모되고 염색이 바랜 채 나타나 있다. 굳이 작품의 이미지를 말한다면, 몸이 만들어낸 흔적들, 즉 손과 발이 셀 수 없이 반복해서 닿았음을 증명해주는 매트 위의 허연 자국들이다. 이 무형의 얼룩 자국들은 요가를 위해 바닥에 수평으로 펼친 매트와 그 위에 수직으로 서거나 앉은 몸이 서로 교차한 접촉 지점들이다. 그런데 이것들은 지면과 몸 사이의 수평·수직의 균형 속에서 생겨난 흔적일 뿐 아니라 또한 몸과 마음 사이의 평형이 낳은 흔적들이기도 하다. 몸이 몸 바깥의 자연 혹은 우주의 힘과 균형을 이루어야 하듯이, 몸은 자신의 안이라 할 수 있는 마음 혹은 영혼과도 평형을 유지해야만, 요가는 성립될 수 있다. 사실 요가의 핵심은 서로 대응하는 이원적 요소들 간의 조화로운 관계를 추구하는데 있다. 아트만(atman)으로 불리는 본래적 자아와 우주 사이의 조응을 위해, 요가는 신체의 힘과 자연의 힘 간의 균형을 추구할 뿐 아니라 몸과 마음(영혼) 사이의 평형, 호흡인 들숨과 날숨의 균형 등 그야말로 실체와 비실체 사이의 소통과 일치의 관계를 지향하는데 주력한다.

-

요가 경전인 『요가 수트라』 제1장에서 정의하는 내용을 보면, 요가는 명상과 호흡, 몸의 긴장과 이완이 결합된 몸과 마음의 수련법이라고 되어 있다.[15] 요가라는 어휘도 몸과 마음을 조화롭게 결합한다는 뜻의 산스크리트어 ‘yuj’에서 비롯됐다고 한다. 따라서 요가에서 중시하는 몸과 마음의 결합, 즉 둘 사이의 평형의 문제는 이번 전시에서 다루고자 하는 ‘몸과 마음의 기하학’이 추구하는 균형의 문제, 즉 심신의 이원적 일원화와도 부합하는 것이다. 이렇게 안(마음)과 밖(몸)을 연결하여 소우주인 자아(atman)를 성찰하는 일이 요가의 목표라고 하면, 역시 몸의 균형 못지않게 중요한 것이 마음의 평형일 수밖에 없다. 이를 위해서 마음의 번잡한 움직임을 가라앉히고 고요한 내면으로 집중하는 실천이 무엇보다 필요하다. 이것이 요가의 명상 수행이다. 잡다한 생각을 지우고 마음을 깨끗이 비우는 이 명상의 의미를 유학에서는 허명(虛明)한 본래 마음으로의 회귀로, 불교의 경우에는 공(空)의 실천이라고 바꾸어 말한다. <몸의 기하학>이 제목으로 명시한 몸을 직접 보여주지 않는 이유도, 요가 수행자의 몸과 하나 된 보이지 않는 마음을 암시하기 위함이며, 결국 몸과 마음의 잠재적 일치 내지는 양자의 이원적 일원성을 직관하도록 하게 하기 위함이라고 생각된다. 매트 위에 드러난 비정형의 흔적들은 따라서 신체와 물질 간의 접촉만이 아니라 몸과 마음 사이의 균형을 나타내는 자국들이 된다. 또한 어둠 속 섬광이 남긴 흔적처럼, 비실체적 형상인 마음이 몸 위를 스치고 지나간 자국이라 보아도 무방하다. 왜냐면 심신의 관계에서 몸은 마음의 궤적이고 흔적으로 간주될 수 있기 때문이다. 일정한 형상을 표현하지 않은 <몸의 기하학>, 그 침묵을 통해 관객은 더 효과적으로 내면화되고, 흔적이란 잠재적 실체에의 암시를 통해 본래적 존재 의미를 직관할 수 있을 것이다.

-

<몸의 기하학>이 표현하고 있는 몸은 확실히 종래의 형이상학이 자기 충족적이라고 규정해왔던 방식의 단독자로서의 몸이 아니다. 작가가 이 작품에서 말하고 있는 몸은 마음과 함께 공존하는 몸인 동시에, 마음과 분절되면서 안과 바깥으로 열린 몸이다. 안의 마음을 바라보면서도 바깥에 기입된 몸(l’excription du corps)인 것이다. 작품이 나타내고 있는 것, 즉 수평과 수직의 방향으로 교차하며 접촉하는 매트와 신체의 균형은 몸과 마음의 이원적 균형과 일치를 암시하며, 그로 인해 관객은 존재의 본래적 의미를 관조하게 된다. 작품의 의미가 이렇게 마음과 몸, 안과 바깥 사이의 경계에서 양자의 접촉을 통해 생성된다는 사실은 필자로 하여금 다시 한 번 더 낭시의 『코르푸스』로 되돌아가게 한다. 왜냐하면 여기서 낭시는 몸이 구체적인 살덩어리의 실체임을 전제하면서도, 동시에 몸이 마음(영혼)의 바깥 존재이며, 외부세계로 열려있는 실체라는 관점을 제시해주기 때문이다. 이 유익한 관점에 기대어서, 필자는 몸이 내면과 외면이 있는 보자기로 상상될 수 있다고 본다. 몸이 내면으로는 마음을 감싼 보자기면서, 동시에 외면으로는 세계에 그 마음을 펼쳐 보이는 실체로서의 보자기라는 뜻이다. 몸-보자기가 마음을 감싸고 풀어낼 때마다, 몸과 마음 사이의 접촉은 당연히 흔적을 남길 수밖에 없다. 그리하여 <몸의 기하학>에서 매트에 나타난 흔적은 일차적으로는 실체인 몸이 외부세계 물질과 접촉하면서 남긴 흔적으로 간주되나, 이차적으로 몸이 마음이라는 내재적 원인과 접촉하면서 생성된 흔적이기도 하다라는 것이 필자의 생각이다.

-

매트 위에 보이는 비정형의 흐릿한 흔적은 미분화된 상태로 남아있던 마음의 잠재적 상태를 매우 잘 암시한다. 그리고 잠재적 층위의 마음이 몸과의 접촉으로 차츰 분화되면서 모양과 질을 가지고 서서히 현실화되는 과정을 설득하는데, 이보다 더 효과적인 이미지는 있을 수 없다고 여겨진다. 이것을 들뢰즈의 ‘되기(devenir)’ 개념과 ‘펼침 (unfolding)’ 개념으로 다시 살펴보아도 마찬가지로 설득력을 잃지 않는다. 마음이 살아있는 알처럼 내재적 원인으로 잠재되어 있다가(잠재성의 층위), 몸이라는 실체와의 접촉과 자극에 따라 분화되면서(개체성의 층위), 구체적인 형태의 흔적 혹은 형태를 가지게 되는(현실성의 층위), 이 일련의 마음의 현실화 내지 펼쳐짐의 과정은 이번 전시에 소개된 작품들 중 <몸의 기하학>이 가장 잘 표현해내고 있는 부분이다. 심지어 크리스테바가 언어의 의미생성 과정을 설명하기 위해 설정한 이중 구조인 코라-세미오틱의 심층적 미분화 상태와 생볼릭의 표면적 현실화도 두 영역 간의 교차적 연동 작용으로 인해 수직 수평의 이원적 구조로서의 인용이 가능하다.

-