2003

Barbara Matilsky │ Kimsooja

2003

Linda Yablonsky │ Mandala: Zone of Zero

2003

Nicolas Bouriaud │ Interview

2003

조너선 굿맨 │ 익명성의 조건: 김수자의 행위 예술

2003

Jonathan Goodman │ Conditions of Anonymity: The Performance Art of Kimsooja

2003

Julian Zugazagoitia │ An Incantation to Presence

2003

Maria Brewinska │ Kim Sooja: Being and Sewing

2003

Flaminia Generi Santori │ Interview

2003

Mary Jane Jacob │ Buddha Mind/Kimsooja Conversation

2003

아담 심칙 │ 김수자: 2003년 3월 24일

2003

Adam Szymczyk │ Kim Sooja: March 24, 2003

2003

Soyeon Ahn │ Kimsooja

2003

안소연 │ 김수자

2003

김찬동 │ 김수자의 바느질

2003

Kimsooja │ A One-Word Name Is An Anarchist's Name

2003

김수자 │ 한 단어 이름은 무정부주의자의 이름이다

A Laundry Woman - Yamuna river, India, 2000, 10:30 video loop, Silent.

A Laundry Woman - Yamuna river, India, 2000, 10:30 video loop, Silent.

Kimsooja

Barbara Matilsky (Curator of Exhibitions Ackland Art Museum)

2003

-

"My work explores the awakening of the self and the other... It is an awakening of the hidden meanings in elements of our mundane lives, to which the viewers previously haven't paid much attention."

-

Growing up in South Korea, Kimsooja describes her complex spiritual background informed by Buddhism, Catholicism, and a code of moral conduct influenced by Confucianism. After high school, she intentionally "stepped out of organized religion in order to experience the real world". The artist felt uncomfortable with the systematization of beliefs and behavior within the faith traditions. Although Kimsooja does not practice Buddhism formally, her beliefs and personal practices strongly parallel this philosophy of life.

-

A Laundry Woman (2002) is a video projection that suggests the harmony of the universe through its stillness and tranquility (figs. 25 and 26). It documents a meditative performance by the artist along the Yamuna River in North India. Videotaped from a slightly elevated vantage point and seen from the back, Kimsooja's figure is silhouetted against blue, opalescent waters. Although the sky is not visible, the viewer is made conscious of its presence by the reflections of flying birds in the water. The artist remains perfectly still while the video captures her state of quiet mindfulness.

-

Kimsooja describes her experience during this meditation: "In the middle of the performance, I was completely confused...[about] whether it is the river which is running and moving or myself." The artist's perceptions of space and time were turned upside down and mentally she became completely immersed in and at one with the water. She later realized that it is not the river that constantly changes but her body, which is transforming all the time: "My body will disappear while the river is still flowing."

-

While watching the video, the viewer slowly becomes aware of the ritual offerings and ashes of deceased people who were cremated at a site along the river. The cycle of life and death becomes a powerful theme in the work. Kimsooja began thinking of the decomposed bodies that floated before her. She meditated on "their lives and their memories and was trying to purify their bodies as well as mine. Praying for their future life with compassion for human beings." The artist experienced a heightened sense of what she describes as "awakeness", particularly in her awareness of the relationship between nature and the body, stillness and movement, life and death.

-

By interpreting the confluence of river and atmosphere, Kimsooja highlights an idea embraced by many artists in the exhibition: the unity of life. She describes the effect of blending water and sky as a mirror presenting both reality and its opposite dimension. From a formal perspective, the artist conceives the river as a surface that is similar to a two-dimensional canvas. There is a strong impulse towards abstraction in A Laundry Woman, which reflects Kimsooja's early career as a painter.

-

Through the video, the artist invites the viewer to share her meditative experience. As she explains, "That is why my body is facing against the viewer. Look at what I look at. I do not present my ego, my identity." Kimsooja's desire for the viewer to "wear" her body suggests the idea of the artist as mediator in order to open possibilities for other people to participate in a "certain awareness and awakening." She points out that there are few opportunities in daily life to achieve this concentrated state of mind.

-

In A Laundry Woman, Kimsooja's body in essence becomes an offering for others to use in order to achieve an expanded consciousness. "Some people referred to me as a shaman who mediates between the dead and the living. I sometimes feel that way too because, in a way, I am doing that all the time. I think it comes from compassion. Understanding others' suffering. Sharing suffering. Sharing love." For many people familiar with India, the title of the work may conjure images of the low-caste women whose livelihood revolves around the river. In this interpretation, the artist becomes the laundry woman in an act of empathy.

-

While discussing the idea of pairing A Laundry Woman with a small sculpture of Buddha Shakyamuni touching the earth to witness his enlightenment, Kimsooja immediately responded to the shared symbolic gesture in the two works of art (fig. 4). She noted that her video establishes connections between the individual and nature; similarly, the Buddha links himself to the land. Through the body, she also connects herself with other human beings from all cultures. As she explains, "All human activities are about linking the self to the other."

-

Relationships are a central theme in a group of installations that depict sewing as a metaphor for threading together different aspects of life. Kimsooja conceives her video works as "invisible sewing." The artist created another work with the title of Laundry Woman (exhibited at the Kunsthalle in Vienna and the Zacheta Gallery of Art in Warsaw, 2002), an installation consisting of suspended fabrics that suggest linens drying outdoors. These materials become symbols of women, love, the body, and sleep. On a social level, they are associated with women's roles in society. For Kim, cloth transcends its materiality and functions as "a container for the spirit"; people are swathed at birth and at death in cloth, and it is also used ceremonially in weddings and other rites of passage.

-

The Laundry Woman also relates to a group of works called Bottari — beautifully wrapped bundles of used Korean bedcovers, fabrics that are either manufactured or sewn by mothers and daughters as shared experiences. These pieces of cloth remind us of the cycle of life; they are used to bundle together household possessions when leaving home, and they help to establish domestic comfort in the absence of a true shelter. Their stitches bind people together.

-

Kimsooja insists that what is most essential is not the body of work but the questions that it raises. She hopes that the viewer will participate in her works by sharing this inquiring state of mind. When asked what her hopes were for the museum visitor, she replied, "I would like the audience to share with me the experience I had during my performance, question and answer, and really put each one's state of mind and body into that position."

— Interviewed by Barbara Matilsky, August 2003.

- Barbara Matilsky, Curator of Exhibitions Ackland Art Museum, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Formerly curator at the Queens Museum of Art, New York City, where she organized the traveling exhibition, Fragile Ecologies: Contemporary Artists' Interpretations and Solutions (1992).

Mandala: Zone of Zero. 2003, 4-channel sound installation with jukebox, mixed sound from Tibetan monk chant, Gregorian chant, and Islamic chant, 9:50 loop.

Mandala: Zone of Zero. 2003, 4-channel sound installation with jukebox, mixed sound from Tibetan monk chant, Gregorian chant, and Islamic chant, 9:50 loop.

Mandala: Zone of Zero

2003

-

Visitors arriving at this gallery, recently relocated to midtown from Harlem, will step into a darkened room carpeted and painted meditative, deep-space blue. Sitting down risks becoming entranced by the little bubbles moving around one of the four circular red-yellow-and-blue jukebox speakers placed on each wall, where they emit a warm, tap-room glow.

-

Some viewers may be as struck by the speakers' resemblance to Tibetan mandalas (symbolizing the design of the universe) as was Kimsooja, who arrived in New York from South Korea in 1998 and saw in these artifacts of American pop culture a perfect meld of East and West. Others maybe reminded of stained-glass windows, since what pours out is an ethereal mix of Gregorian, Islamic and Tibetan chants that circulate, like those bubbles, in an endless loop of male voices, both rumbling and sweet.

-

In her previous installations and videos, Kimsooja focused on the body as a protective cover for powerful emotions. Korean textiles figured prominently, wrapping immigrants or outcasts as they moved from place to place with belongings that survived them and were passed to others. It is the unmoving viewer being wrapped this time, in waves of sound and light. But because there is more here to experience internally than to see, viewers may dismiss the work as a literalized notion of the-gallery-as-chapel in which to worship at the altar of art, without realizing that they are part of the ritual.

— From TimeOut, New York: November 27 - December 4, 2003.

A Needle Woman - Kitakyushu, 1999. Single Channel video. 6:33 loop, Silent

A Needle Woman - Kitakyushu, 1999. Single Channel video. 6:33 loop, Silent

Interview

2003

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

In Buddhist philosophy, there is a notion which has a great importance: the impermanence of the world we live in. The needle woman stands in front of passing-by elements, like as if you were stressing on this impermanence, or on the fluidity of things. How does the Eastern way of thinking match contemporary art history, in you work? -

Kimsooja

The impermanence of our lives is an important notion in my work and thinking and with this perception, comes a deeper compassion for human beings. Meditation about impermanence has been shading in my work since I first started the sewing pieces in the early 80's — connecting fragments of my deceased grandmother's clothes. -

Buddhist philosophy, especially Zen Buddhism is similar to the way I perceive and function in the world. However, the ideas in my work are created from my own questions and experiences, not from Buddhist theory itself. (It is more complicated — as I was brought up formally a catholic, and practiced also Christian for some time, but Korean daily life practice is greatly dominated by Confucianism, mixture of Buddhism, and Shamanism.)

-

Certainly, where my immediate perceptions and decisions in art making meets the disciplines of Buddhism — making art and living my life are not consciously borrowed from theories. I intentionally stopped reading over a decade ago to concentrate and follow my own thoughts, but I recently started reading again especially on Buddhism as I find amazing similarities in my work and perception of life in it.

-

I might add that, the Eastern way of thinking inhabits every context of contemporary art history not just as a theory but as attitude melded in ones personality and existence and is inseparable with Western thinking.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

Do you think that oriental (eastern) thought has a real impact on the contemporary art world, or is it only a postmodern kind of exoticism, a decor for western aesthetic investigations? -

Kimsooja

It would be unfortunate if the Western art world considered Eastern thought as a decor for Western aesthetic investigation — as if it were another element to add without noticing the fact that it is a way — in the process of making art. It is always there — as a dialectic — in all basic phenomena of art and life together. Eastern thought often functions in a passive and reserved way of expression, usually invisible, non verbal, indirect, disguised, and immaterial. Western thought functions more with identity, controversy, gravity, construction in general rather than de-construction, and material than immaterial compared to Eastern. The process finally becomes the awareness and necessity of the presence of both in contemporary Art. It is the 'Yin' and 'Yang' — a co-existence that endlessly transforms and enriches. -

Nicolas Bouriaud

You could have chosen to ignore your Korean cultural background, but you decided to use it as a material. In a way, especially the Bottari series, your work Post-produces formal elements from this already existing Korean shapes and patterns. But formally speaking, your exhibitions are playing with minimal art. Would minimalism play a special role onto this connection between East and West? And which movements or artists were the most influential for you? -

Kimsooja

I have always used my personal life as the basic material for my work — hoping it would embrace the other. If I hadn't grown up and lived as a married woman in a Korean society, I wouldn't have chosen these traditional bedcovers. In Korea, they have a special meaning as the bed is the site of birth and death — of sleeping, loving, suffering, dreaming dying — it frames our existence. The bedcover is given to and used by newly married couples in Korea with messages beautifully embroidered and emblematic of wishes for love, fortune, happiness, many sons, and a long life.... it is so easy to notice it's contradiction when we see these symbols. I can't interpret my own culture with other culture's materials in the same way..... I try to find materials in their own context, but it always ended up with me bringing materials from Korea as theirs looked so neutral and hard to get the sense of the energy I feel from ours. -

As for minimalism, I agree with you as a part of the nature of my practice but in the sense of extension of it's interpretation to the life as well as formalistic terms. The Japanese art critic Keiji Nakamura perceives my work as 'existential minimalism,' and this makes sense to me also. I greatly respect minimalism in the sense of the process of making art as well as it's vision. However the contents minimalists deal with are often maximal. It's hard to name any particular artist who was influential to me as I've been influenced in a way from anyone whom I have an opinion on their work-even from the ones we don't agree with. Yet, there is one statement by John Cage I saw it written in the bottom corners of an empty container at the 1985 Paris Biennale; that has reverberated for a long time in my mind. "Whether we try to make it or not, the sound is heard.".

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

You are partly working with objects and surfaces made by other people. Of course the readymade is not a stake anymore, but in your case it could be questioned on a social or psychological level. The notion of existential minimalism could bring us to this direction, too, because it carries the idea of humanity, concrete people making products in a particular context. So what is the status of those objects in your mind and in your work in general? Is it a neutral process to use those bedcovers, or do you consider their context of production and the condition of the workers? And, more generally, what is the status of pre-existing things in an artwork? -

Kimsooja

Analyzing the nature of my already-mades, can give a significant clue to the context of my work. I've been using objects from Korean domestic daily life significantly in my series, 'Deductive Object' from the early 90's. Here, I chose traditional Korean domestic already-mades; wooden window frames, reels, drums, and agricultural tools; a saw, shovels, forks, hooks... and wrapped them with old Korean clothes and bedcovers. -

Now, I as am working exclusively in New York, I'm using objects found here; a child's toilet, a swing, vessels and an old directory board from a department store...etc. I've been thinking more about people who owned and used the objects and their traces rather than the people who made or manufactured them in those objects and I'm noticing that they are symbolically genderized in form and function.

-

Perhaps we need to re-define the notion of readymade in a larger context than relying on Marcel Duchamp's investigation — especially in this mass producing, global networking era which needs constant re-definition. My work is about pre-existing things buried into our daily lives — not mentioned nor conceptualized in art history.

-

My work also includes a presentation of the daily life of women's labor and her domestic performance trying to re-define the social, cultural and esthetic meaning of it to create it's own context in contemporary art history.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

This concept of pre-existence of things is very interesting. In a way, one could say that you are working with the ghosts of the objects, their aura, trying to turn the invisible into a shared experience. The anonymous is supposed to be invisible; so is the past, mostly. Is that important for you to make them visible? -

Kimsooja

Yes. Depending on the nature of the already-made objects, my interest lies on different issues; for example, when I work with bed covers, I am working with pre-existing objects focusing more on the fact of 'pre-used' rather than 'pre-made' as I am more focused on anonymity of the bodies and the destinies of the couples rather than on anonymity who made the bed covers, although I am concern about the people who made them. -

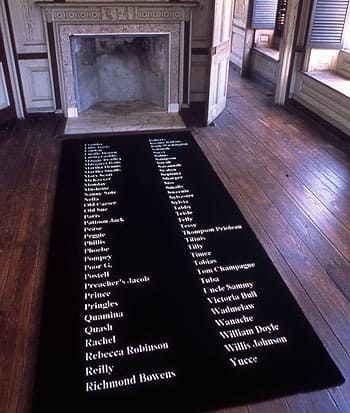

On the other hand, the folklore objects I've used, my interest lies more on the genderized nature and esthetic structure of the object and it's function in daily life rather than the anonymous beings who made or used them. But when I made a series of carpets which embeded names of the African American slaves who used to work for the plantation houses in the US, I was trying to combine the nature of the painstaking labor of carpet weavers and that of the African American plantation slaves emphasizing both of theirs hardships as I find carpet weaving and plantation job is similar jobs in different dimension. I wish to reveal this anonymity — as myself — one of the anonymous.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

The Needle woman is a central figure in your video works: You are standing in front of people and objects, right in the middle of a maelstrom of things, as if you were out of the world. Is that another figure of anonymity (the voyeur? Or are you even more into the world by watching it pass?) -

Kimsooja

It is the point of the needle which penetrates the fabric, and we can connect two different parts of the fabrics with threads, through the eye of the needle. -

A needle is an extension of the body, and a thread is an extension of mind. The traces of mind stays always in the fabric, but the needle leaves the site when it's medialization is complete. The needle is a medium, a mystery, a reality, a hermaphrodite, a barometer, a moment, and a Zen.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

Watching the needle woman, I was also thinking about a negative image of the baudelairian flaneur, an archetypal figure of the occidental modernity. Are you inscribing your work in the field of modernity, or is it a notion that is totally irrelevant for you? -

Kimsooja

It is interesting to see my work discussed in this way — being compared to others from a completely different culture and social identity and also born at different time and space. My work is focused on the totality of life and art. One can see different realities in one persona or in art. Perhaps that is why one sees diverse similarities in my work. -

Nicolas Bouriaud

In a way, you are trying to capture the totality of human experience, which is quite rare. As you said, your work is not about any particular issue? Can you tell me what this ambition implies, and means? -

Kimsooja

Totality is the truth and the reality of things. And it takes time to clarify in language as a whole. I am interested in approaching the reality that embraces everything because it is the only way to get to the point without manipulations. Most people approach reality from analysis or 'from language to colligation' which is the truth', but I am proposing a 'colligation to be analyzed' by audiences. My working process is intuitive and I believe it's own logic. If I have an ambition, it is to be just a 'being' who has no need to be anyone special, but is freed from human follies and desires — without doing anything particular. 'Being nothing/nothingness' and 'making nothing/nothingness' is my goal. It is a long process. -

Nicolas Bouriaud

To be "freed from desires" sounds very buddhistic. Is the artist a kind of boddhisattva, who tries to free himself/herself and to liberate the viewer? -

Kimsooja

I remember the way desire was talked about in the 80's through the work of "simulationnist" artists such as Jeff Koons or Haim Steinbach : art was the absolute object of desire, a "pure merchandise," a perfect exchange value. Desire was examined in terms of compulsion and acquisition. So today, what would be the relationships between art and desire? -

In any case, artists have been constantly dealing with their own desire and audience. For me, artists' practices are similar to that of Buddhist monks' in the sense that they both try to liberate and to become beyond themselves. In this era of globalization and technology however, the self, the body, the spirit, and the other can be perused in many ways -Artists deal with different types of desires depending on their social and cultural context. Desire can be visualized in a physical object form which satisfies sense of 'possession' or in a psychological and metaphorical way that deals desire as another 'subject'. When Claud Viallat said 'Desire leads', I think he referred to another origin of art instinct which links and visualizes these two different source of desires. Artists cannot help ask what is the origin of their desire, and what role desire plays in their work. To understand that this is 'the subject' an artist confronts in the end, and to extinguish it.

─2003 Solo Exhibition Catalogue, 5 Continents Editions, pp. 45-57.

- Nicolas Bourriaud is a contemporary art critic and the director of Documents sur l'art, a bilingual magazine devoted to contemporary culture.

익명성의 조건: 김수자의 행위 예술

2003

-

한국 태생의 뉴욕 기반 작가 김수자의 예술 세계에서 우리는 익명의 존재라는 개념 위에 세워진 하나의 전체 커리어를 본다. 익명의 존재라는 개념은, 자아의 솔직한 주장에 통상 반하여 작용하는 힘과 환경에 어우러지려는 소망을 드러내는 메타포다. 김수자의 예술은 항상 예상을 뒤집으며 이것은 그가 세계를 포용하는 한 가지 방식이다. 김수자의 자아 퍼포먼스는 대립인 동시에 묵종이며, 운명의 순응인 동시에 의지의 표출이다. 김수자의 명백히 익명적인 행위에는 엄청난 힘과 주장이 있으며, 그것은 도전인 동시에 운명의 인정이다. 김수자가 대립물로서 제시하며 다루는 바로 그 환경들은 자아가 자기 자신을 규정하기 위해 꼭 필요한 것이라고 해도 좋을 것이다—전체가 부분을 규정하는 것과 비슷한 이치에서 말이다. 김수자는 어떤 통합된 알아차림(awareness)을 획득하기 위한 싸움 속에서 이름 없이 홀로 서 있다. 이 알아차림이라는 말의 정의들은 경계 없는 흐름 속에 있기에 어쩌면 불교적으로 보일 것이다. 익명성을 정교하게 구축함으로써 김수자는 자아를 지우려는 욕망, 그리고 그가 침묵 속에서 웅변적으로 맞서는 환경을 대면하기 위해 필요한 결단 사이의 대립적 모순들을 예리하게 알아차리는 감수성을 보여준다.

-

<바늘여인(A Needle Woman)>(1999~2001) 퍼포먼스에서 김수자가 도쿄의 시부야 거리를 오가는 행인들 한가운데 서 있을 때 그의 위치는 안티테제로 시작되지만, 시간이 지나며 이는 인간의 회복력에 대한 무언의 긍정, 심지어—자기 자신에게 익명성의 조건을 부과하고 있음에도 불구하고—개인의 가치에 대한 무언의 긍정이 된다. 놀라운 가치의 전환 속에서 김수자의 행위들은 말 그대로 죽음이라는 자신의 한계를 점점 더 인식해가는 자아의 발전을 구현하고, 그는 마치 언제나 제 시간보다 한발 앞서 존재하는 죽음을 애도하고 있는 것만 같다. 그러나 김수자의 시각에서 나타나는 전반적인 지향점은 어둡거나 섬뜩한 것과는 거리가 멀다. 김수자의 예술은 삶의 환경을 암묵적으로 수용하는 통찰적 인식을 드러내며, 그가 다양한 문화와 교류하는 것—김수자는 <바늘여인> 퍼포먼스를 전 세계 여덟 개 도시에서 선보였다(순서대로 도쿄, 상하이, 델리, 뉴욕, 멕시코시티, 카이로, 라고스, 런던)—은 어느 환경에서든 존재를 긍정하는 것이나 다름없다.

-

김수자가 예술가로서 성장한 과정은 꾸준하고도 분명했다. 1957년 한국 대구시에서 태어난 그는 서울 홍익대학교에서 회화를 전공하고 1984년 동 대학원을 졸업했다. 이후 반년간 프랑스 정부의 보조금을 받으며 프랑스에서 지냈다. 1992~3년에는 뉴욕 P.S. 1 현대미술관(P.S. 1 Contemporary Art Center) 레지던스 입주 작가로 미국에 왔다. 문화적 망명을 선택한 그는 1998년에 다시 뉴욕으로 돌아왔고 이후 미국에 정착해 이곳에서 점차 더 큰 인정을 받으며 국제적 명성을 누리는 예술가로 성장했다. 화가로 보낸 시간은 그리 길지 않았지만 그는 줄곧 표면의 문제를 탐구하는 데 관심이 있었기에 예술가로 활동하는 내내 이 질문에 대한 탐구를 이어왔다. 실제로 김수자가 말하길 "이러한 [표면의] 탐구는, 예술적 자유를 추구하는 나의 의지와 더불어, 나의 예술에서 새로운 지평을 여는 것을 가능하게 했다." 표현 방식의 변화는 빠르게 찾아왔다. 일찍이 1983년, 그러니까 아직 대학원에 재학 중일 때 김수자는 "1983년 나는 전통적인 이불보를 바느질하던 중에 예술과 삶을 질문하는 수단으로서 바느질이라는 방법론을 처음 발견했다." 김수자는 일상생활에서 쓰는 직물을 새로운 종류의 캔버스로 활용하기로 결정했다. 그러나 바느질이라는 행위는 애도와 뗄 수 없는 개인적인 행위이기도 했다. "나는 헌 옷을 바느질하는 작업을 한 해 전에 돌아가신 할머니가 남긴 옷가지로 처음 시도했다."

김수자는 캔버스 표면을 "화가가 극복하기를 소망하는 장벽이며 장애물"로 보고 이것에 관해 질문하는 화가로서 시작했다. 10년의 세월에 걸쳐 김수자는 다양한 매체와 전략—비디오와 퍼포먼스—을 통합하는 새로운 단계로 이행했고, 이 과정에서 작품의 강조점은 표면의 문제에서 이제 그가 새로 인식한 언어인 둘둘 만 헌 옷과 이불, 즉 이미지 봇짐(an image bundle)으로 이동했다. 김수자 예술의 변화는 갈수록 더 상징적인 재료의 사용을 중심으로 전개되었다. 어째서 이불보를 사용하느냐는 질문에 김수자는 이렇게 답한다. "이불보는 상징적인 장소다. 우리가 태어나고, 쉬고, 사랑하는 곳이며, 꿈꾸고, 앓고, 마침내 죽음을 맞이하는 곳이다. 그것은 몸의 기억을 살아 있게 하고, 그 기억들은 또다른 차원을 만든다." 이제 김수자는 퍼포먼스와 비디오의 세계에 집중한다. 자신의 환경을 더욱 알레고리적으로 읽는 쪽으로 방향을 틀었고 그러한 독해 안에서 김수자의 삶과 행위는 우리의 삶과 행위를 대표하는 한 존재로서 기능한다. 김수자는 우리의 행위가 내면 깊은 곳의 고립을 드러내며, 우리의 유한한 시간 앞에서 행동은 전형적(paradigmatic) 의미를 띤다는 인식을 우리 모두가 공유한다는 것을 이해하기에, 인간의 조건을 본질적으로 익명적인 것으로 받아들인다. 김수자의 예술에서 우리의 죽음에 대한 이해는 그가 한 개인으로서 관객을 위한 매개체가 되어줌으로써 명료해진다. 김수자의 행위들은 관람자와의 존재론적 대화 속으로 들어오기 때문에 관람자에게 울림을 준다. 이 대화는 죽음의 현존이 연상시키기 마련인 높은 도덕적 진지함으로 가득하다. -

<바늘여인>은 군중 한가운데에서 본래 사색적 성격을 띠는 울림 있는 침묵을 제시함으로써 우리 모두가 느끼는 고립을 행위로 구현한다. 김수자는 불교 수행자가 아님에도 최근의 퍼포먼스에서 선불교와 친연성을 발견한다. 김수자의 예술은 자신의 수행을 오롯이 알아차리는 명상하는 정신을 연상시킨다. 그는 자기 자신의 감각을 거부하고, 세계의 에너지—또는 소음—을 흡수함으로써 치유하고 결속시키는 태도를 선택한다. 김수자 스스로 말하듯 "[1983년부터] 10년간의 바느질 수행 끝에 나 자신을 자연의 직물을 엮는 바늘로 여기게 되었다."

-

작가는 바늘과 실크의 정밀한 메타포로 표현되는 무아(selflessness)의 행위로서 실재의 이질적인 부분들을 한데 모으고자 한다. 김수자가 여덟 개 도시에서 군중과 나누는 말없는—심지어 기도하는 듯한—상호작용은 완강한 목적의식뿐 아니라, 부동의 상태와 침묵이 자아내는 다양한 반응을 안전하게 흡수할 수 있도록 의도적으로 지운 자아를 보여준다. 비디오는 김수자의 활동을 직접 보면서 상호작용들의 아카이브를 창출한다. 흥미롭게도, 김수자는 여러 도시에서의 활동을 기록하는 비디오의 활용 역시 메타포적으로 바라본다. "관객들이 내 퍼포먼스의 결과물인 비디오를 볼 때 또다른 마주침이 발생한다. 내 몸은 바로미터의 역할을, 서로 다른 시간과 공간의 사람들을 잇는 바늘의 역할을 한다." 퍼포먼스가 지속되는 내내 김수자는 자아가 가장 우선한다는 환상을 소멸시킴으로써 사람들을 결속시키는 매듭을 강조하려고 한다.

-

김수자의 11일에 걸친 서사시적 여정 〈떠도는 도시들 – 2727km 보따리 트럭(Cities on the Move—2,727 Kilometers by Bottari-Truck)〉(1997년 11월)은 그의 기억 속 장소들을 되짚는다. 김수자는 색색의 보따리를 트럭 가득 싣고 과거에 살던 도시와 마을을 여행했다. 김수자는 이 퍼포먼스가 "기억과 역사를 싣고 있는 사회적 조각(social sculpture)으로서 물리적·정신적 공간을 찾아내고 동등화한다"고 여긴다. 김수자가 태백산을 지나는 모습을 목격하는 이 비디오는 그가 과거와 마주하려고 애쓰면서 지고 가는 문자 그대로의 짐을 감동적으로 보여준다. 이 퍼포먼스는 김수자의 여행을 우리 존재의 서사에 대한 메타포로 제시한다. 이 전시회 도록에서 김수자가 말하듯 "'보따리 트럭'은 공간과 시간을 가로지르는 과정적 오브제(processing object)로서 그곳/우리가 떠나는 곳/우리가 가는 곳에 우리 자신을 데려다놓는 동시에 그로부터 떠나게 한다." 비유적 언어는 관객을 형이상학적 차원으로 끌어들여 그의 여정을 우리 여정의 상징으로 읽기를 요구한다. 김수자의 탁월함이 특히 잘 드러나는 때는 그의 이미지들이 알아차림의 상징적 표현으로 제시될 때다. 길을 따라 이동한다는 개념은 그 사람이 사라지면 그 길도 끝난다는 불가피한 결말과 깊이 공명한다. 아직 실현되지 않은 프로젝트들에 관해 이야기해 달라는 질문에 김수자는 도록에서 이렇게 답한다. "나는 내 프로젝트들을 내 몸 안에 갖고 있으며 내게는 몸이 내 스튜디오입니다. 나는 그것들을 모두 기억하거나 설명하려고 하지 않습니다." 이 진술은 김수자는 창조성의 원천을 자신의 몸 안에 갖고 있으며, 그것은 그가 그토록 세심하게 제시하는 익명적인 공적 자아의 대응물로 작용한다는 것을 우리에게 다시금 환기한다. 우리가 김수자의 퍼포먼스 비디오에서 그의 얼굴을 결코 보지 못하는 것이 사실이라면 이는 김수자의 익명성이 그를 둘러싼 세계에서 일어나는 모든 일을 아우를 만큼 충분히 크기 때문이다.

-

김수자가 머문 기억에 남겨진 발자취를 따라가다 보면 그가 밟는 길(道, path)—이 자체로 불교 용어다—의 함의는 불교와의 깊은 친연성을 시사한다는 것이 분명하게 보인다. 김수자가 "관조하는 자세와 방법은 불교 수행자의 그것과 유사하다"고 작가 스스로 언급한다. 동시에 김수자는 "자기 자신만의 방식으로 세계를 관조하고 자기 자신만의 길이 이따금 사유의 드넓은 흐름과 만날 수 있는 독립된 개인"으로 남아 있을 권리를 간직한다. 작품의 고립 속에서 김수자는 세계와의 보편적 조응을 추구하지만, 그것은 어디까지나 그 자신만의 방식으로 또한 그 자신만의 경험을 통해서다. 김수자의 알레고리들이 성공적인 이유는 겉으로 보이는 모습과 달리 그것들이 실은 매우 개인적인 목적에서 나온 것이기 때문이다. 어떤 관점에서 김수자의 익명성은 하나의 속임수이자, 한계라는 개념이 무의미할 정도로 그 경계가 확장된 자아의 감각을 이야기하는 한 가지 방식이다. 김수자의 고립에서 특이한 점은 그것이 실제로는 관객과 온전히 교류한다는 데 있다. 김수자는 보편적 함의를 강조하는 한 가지 방법으로서 고독을 제시하는 동시에, 타자들과의 광범위한 연루로 나아가는 한 가지 방법으로서 자율성을 강조한다. 실제로 김수자의 외로운 행위들은 도움을 요청하는 듯 보인다—2001년 라오스에서 촬영된 <구걸하는 여인(A Beggar Woman)> 비디오에서 가부좌를 틀고 앉은 김수자는 손을 뻗어 구걸한다. 누군가 그에게 동전을 건네고, 이 장면은 무성으로 제작되어 작가의 취약한 상태를 더욱 강렬하게 드러낸다. 우리는 이 상호작용을 어디에나 있는 궁핍의 증거로 읽는다. 김수자는 결핍을 극적으로 표현함으로써 자기 자신을—그리고 우리도—욕망들의 무아적 합성물, 완전한 빈곤의 구현으로 환원한다.

-

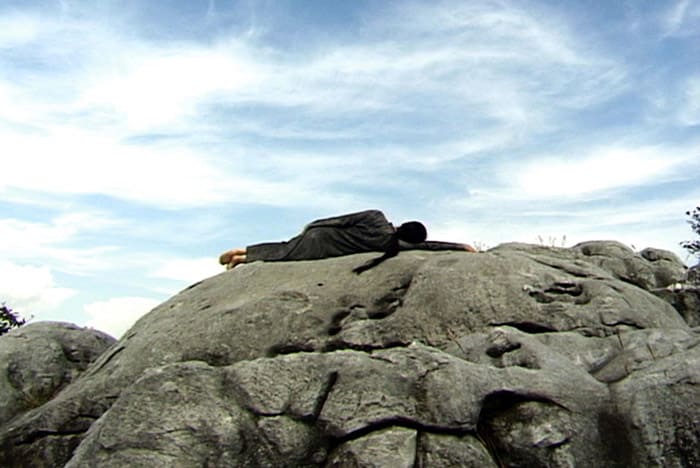

그리하여 김수자는 행위의 언어로 우리의 직관적 앎을 대상화한다. 이 언어에는 그 의도의 벌거벗은 본질만이 남겨져 있다. 그의 작품에는 물론 일부러 낮은 자세를 취함으로써 성취되는 페미니스트적 함의가 있다. 1999년 일본에서 <바늘 여인—기타큐슈(A Needle Woman—Kitakysuhu)>라는 제목으로 선보인 탁월한 퍼포먼스에서 김수자는 석회암 산의 정상에 드러누워 있고, 몸의 곡선은 바위의 솟음을 반향한다. 이 비디오는 예술가의 방법론을 확인해준다. 영상에서 김수자가 자신을 둘러싼 환경들과 나누는 상호작용은 그것들을 하나의 통일된 의지로 감싼다. 어머니 대지에 대한 암시가 도입되고, 여기에는 자연과의 무한한 동일시의 감각이 있다. 아울러, 일부 다른 퍼포먼스에는 정치적 함의가 담겨 있다. <구걸하는 여인> 또는 김수자가 분주한 거리의 보도에 누워 있는 <집 없는 여인—델리(A Homeless Woman—Delhi)>(2000)가 그러한 예다. 사회 변화를 옹호하는 직접적인 메시지의 부재는 이 두 작품에 영향을 주지 않는다. 이들 작품은 고통을 우리의 본질적 조건으로 표현하기 때문이다. 실로, 김수자가 제시하는 전제의 간접성은 그의 표현을 오히려 더 강력한 것으로 만든다. 그의 표현이 그 보편성에 비추어 볼 때 불가피하게 느껴지기 때문이다.

-

최근의 설치 작품 <거울여인(A Mirror Woman)>(2002)에서 김수자는 뉴욕시 피터 블럼 갤러리(Peter Blum Gallery) 가득히 헌 이불보를 매달았다. 아울러 양 벽면에는 거울을 부착해 방문객이 색색의 천으로 이루어진 미로 속을 걷는 동안 그들의 모습이 비치게 했다. 음향적 요소 역시 사용되었다—티베트 수도승의 암송 소리가 전시회장에 흘렀다. 이 작품의 관람 경험은 전반적으로 불편하리만치 내세적이었다. 어쩌면, 가장 넓은 의미에서는 김수자의 개입은 실제로 사람들을 불편하게 만든다. 그것은 우리의 죽음을 환기하기 때문이다. 김수자는 <묘비명(Epitaph)>(2002)에서 브루클린 그린포인트의 공동묘지 한가운데에서 이불보를 펄럭인다. 그 순간 삶은 그것과 명백한 대립을 이루는 죽음과 합쳐진다. 그렇게 이 작품은, 존재와 비존재 사이의 해석이 실은 우리에게 강요된 것에 지나지 않을 수 있음을 시사한다. 언뜻 이분법으로 보이는 것이 실은 한 관념의 두 측면일 때가 있다. 김수자가 예술가로서 발휘하는 강력한 힘은 열정과 고요, 능동과 수동이 하나로 합쳐지는 순간을 발견하는 데 있다.

-

그는 예술이 그릇된 이원성을 동등화하는 위대한 힘임을 우리가 이해하기를 원한다. 우리의 정신은 거의 모든 것이 담길 수 있는 장소다. 김수자는 자신의 넉넉한 비전 안에서 미지의 것에 관한 진실들—우리의 삶 위에, 그리고 우리의 삶 너머에 있는 것—을 반복해 말한다. 김수자는 우리가 암묵적으로 알고 있는 것을 가져와 거기에 공적인 우아함을 입힌다. 김수자가 자신의 예술 안에서 커질수록 우리 역시 커지고, 그리하여 그의 넉넉한 상상력은 우리를 그 안에 그야말로 완전하게 포괄한다.

— 『아트 아시아 퍼시픽(Art Asia Pacific)』, 2003년 가을호. 영한 번역(한국문화예술위원회 후원): 홍정인

- 이 글에 제시된 모든 인용문의 출처는 2002년 여름에 진행된 작가의 서면 인터뷰다.

Conditions of Anonymity: The Performance Art of Kimsooja

2003

-

In the art of Korean-born, New York-based Kim Sooja, we see an entire career built upon the notion of the anonymous as a metaphor for the wish to merge with forces and circumstances usually acting against the forthright assertion of self. Kim's art inverts expectations as a way of embracing the world. Her performance of self is at once oppositional and acquiescent, fated and willed. There is a tremendous strength and assertion in her apparently anonymous actions, which are not so much transgressions as they are recognitions of fate. It may well be that the very circumstances Kim addresses, presenting as oppositions, are what the self needs to define itself — in much the same way the whole defines the part. Kim stands alone, unnamed, in her struggle to achieve a consolidated awareness, whose definitions may be seen as Buddhist in their unboundaried flow. In the elaborations of her anonymity, then, Kim presents a sensibility acutely aware of the warring contradictions between her desire for an erasure of self and the kind of resolve necessary to confront the environment she so eloquently, albeit silently, strives against.

-

When, in the performance A Needle Woman (1999-2001), Kim stands against waves of Japanese passersby on a street in Shibuya, Tokyo, her pose begins as antithesis but becomes, over time, a wordless affirmation of human resilience, even of individual worth, despite the conditions of anonymity she imposes upon herself. In a remarkable transformation of value, her actions quite literally embody the progress of a self increasingly cognizant of its mortal limits — it is as though Kim is mourning death, which is always ahead of its time. Yet the overall thrust of her vision is far from dark or macabre; her art demonstrates a knowing perception of life's circumstances that is by implication assenting, and her engagement with different cultures — Kim has performed A Needle Woman in eight cities throughout the world (in order: Tokyo, Shanghai, Delhi, New York, Mexico City, Cairo, Lagos, and London) — amounts to an affirmation of existence no matter what the environment.

-

Kim's development as an artist has been steady and assured. Born in 1957 in Taegu, Korea, she studied painting at Hong-Ik University in Seoul, where she completed graduate school in 1984. She spent half a year in France, on a grant from the French government. In 1992-93, Kim came to New York as an artist-in-residence at the contemporary art center P.S. 1. Deciding on cultural exile, Kim again returned to New York in 1998; this move marked her permanent stay in America, where she has received more and more recognition, becoming an artist of international reputation. Although Kim did not stay long as a painter, she remains interested in investigating the issue of surface, an activity she has continued throughout her career. Indeed, Kim comments, "This pursuit [of the surface], along with my will towards artistic freedom, enabled me to open up new horizons in my art." The change in expression came quickly to Kim; as early as 1983, while still in graduate school, she first "discovered the methodology of sewing as a means of questioning art and life while I was sewing a traditional bedspread in 1983." Kim made the decision to use fabric in daily life as a new kind of canvas. But the act of sewing was also personal, being tied to mourning: "My first attempt at sewing used clothes was done with the remains of my grandmother's clothing, left behind after her death a year before."

-

Kim began as a painter who questioned the surface of her canvas, seeing it as "a wall and barrier that painters wish to overcome." Over the course of a decade, she moved into new developments incorporating different media and strategies — videos and performances — in which the emphasis shifted from a treatment of surface to her now recognized language of wrapped used clothes and bedding: an image bundle. The changes in her art revolved around an increasingly emblematic use of materials; when asked why she makes use of bedcovers, Kim replies: "The bedcover is a symbolic site. It is where we are born, where we rest and love, where we dream and suffer and finally die. It keeps memories of the body alive, which result in another dimension." Now that she is concentrating on the world of performance and video, Kim has turned toward an increasingly allegorical reading of her environment, in which her life and actions function as an existence representative of ours. The human condition is taken up as essentially anonymous because Kim comprehends that all of us share the recognition that our actions reveal a deep-seated isolation, as well as an unconscious awareness that behavior takes on paradigmatic meaning in the face of our limited span of time. In Kim's art our understanding of death becomes enlightened by her mediation as an individual toward her audience; her actions resonate because they enter into an existential dialogue with their viewers, replete with the high moral seriousness the presence of death inevitably calls to mind.

-

A Needle Woman enacts the isolation we all feel by offering a resonant silence, contemplational in nature, in the midst of the crowd. Kim, who is not a practicing Buddhist, nevertheless sees Zen Buddhist affinities in her recent performances. Her art is suggestive of meditational mind in the encompassing awareness of its practice. She disavows her sense of herself in favor of a stance that heals and binds by taking in the energy, or noise, of the world. As Kim herself has said, "After a decade of sewing practice [since 1983], I came to see myself as a needle weaving the fabric of nature."

-

The artist intends to bring together disparate parts of the real as an act of selflessness represented by the precise metaphor of needle and silk. Her silent, even prayerful, interactions with the amused, bemused crowds in eight cities show a tenacity of purpose as well as a self deliberately obliterated so as to take in, out of harm's way, the various responses her stillness and silence create. Video witnesses her activities, creating an archive of interactions. Interestingly, Kim sees the use of video, which documents her activities in different places, metaphorically as well: "Another encounter occurs when audiences see the video resulting from my performance. My body functions as a barometer, as a needle connecting people from a different time and space." She means to emphasize the ties that bind people, by extinguishing, for the duration of the performance, the illusion that the self is primary.

-

Kim's epic eleven-day journey Cities on the Move — 2727 Kilometers Bottari Truck (November 1997) retraced sites in her memory; she traveled to different cities and villages where she used to live, carrying colorful bottari on a flat-bed truck. Kim considers the performance "a social sculpture, loaded with memory and history, which locates and then equalizes physical and mental space." The video, witnessing Kim's transit in Korea's Taebek Mountains, movingly and also literally presents the baggage she carries with her as she seeks to face her past. The performance presents her travels as a metaphor for the narrative of our existence; as Kim states in a catalogue accompanying the piece, "Bottari Truck is a processing object throughout space and time/locating and dislocating ourselves to the place/where we come from/and where we are going to." The figurative language engages the viewer on a metaphysical plane, demanding that we read her journey as emblematic of our own. Kim is particularly strong when her imagery is offered as a symbolic representation of awareness; the notion of moving along a path resonates in sympathy with the inevitable determination that the path will end when the person is gone. Asked in the catalogue to comment on unrealized projects, Kim replies, "I contain my projects in my body which I find as my studio, and I don't try to remember or describe them all." The statement returns us to the idea that Kim holds within her body a wellspring of creativity, which acts as the counterpart to the anonymous public self she so carefully presents. If it is true that we never see her face in her performance videos, it is because her anonymity is large enough to incorporate whatever occurs in the world around her.

-

As one follows the steps left by Kim in her sojourns of memory, it becomes clear that the implications of her path — itself a Buddhist term — suggest deep affinities with Buddhism. Kim comments that her "attitude and way of looking are similar to that of Buddhists." At the same time, she reserves the right to remain "an independent individual, who looks at the world in one's own way and who recognizes that one's own path can sometimes meet with a broad stream of thought." In the isolation of her artwork, Kim seeks out a generalized correspondence with the world, but on her own terms and from her own experience. Her allegories are successful because they originate, despite seeming otherwise, from a highly individuated sense of purpose. In a way, Kim's anonymity is a subterfuge, a manner of relating a sense of self whose boundaries are so extended as to do away with the notions of limit entirely. The odd thing about Kim's isolation is that it in fact completely engages with her audience; just as she offers solitude as a way of emphasizing universal implications, so she underscores her autonomy as a way of proceeding toward a wide involvement with others. Indeed, her lonely actions appear to call for help — in the video A Beggar Woman, done in Lagos in 2001, she sits crosslegged, her palm extended for alms. Someone gives her some change, and the muteness of the scene intensifies the artist's vulnerability. We read the interaction as evidence of need everywhere; in her dramatization of want, Kim reduces herself — and us as well — to a egoless composite of desires, an enactment of utter poverty.

-

As a result, Kim objectifies our intuitive knowledge in a language of actions stripped to the bare essence of their intent. There are of course feminist implications to her devotions, accomplished with a purposeful humility. In a remarkable performance, entitled A Needle Woman-Kitakyushu, done in 1999 in Japan, Kim stretched out on top of a limestone mountain, her curving body echoing the stony rise. The video confirms the artist's procedure, whereby her interaction with her surroundings envelops them in a unified will. The suggestion of the earth mother comes into play; there is a sense of limitless identification with nature. At the same time, some of the other performances have political implications, as suggested by A Beggar Woman or A Homeless Woman — Delhi (2000), in which Kim lies down on the sidewalk of a busy street. The lack of a direct message advocating social change does not affect the two pieces, which render suffering as intrinsic to our condition. Indeed, the indirectness of Kim's premises actually enhances her expression, which feels inevitable in light of its universality.

-

In the recent installation A Mirror Woman (2002), Kim hung used bedcovers across the width of the Peter Blum Gallery in New York City. She also placed mirrored surfaces on both of the side walls, reflecting the path of visitors as they made their way through a labyrinth of colorful cloth. There was a sound element as well — the chants of Tibetan monks accompanied the exhibition. Overall, the experience of the piece was otherworldly to the point of being disturbing. Perhaps, in the largest sense, Kim's interventions are indeed disturbing, for they remind us of our mortality. In Epitaph (2002), Kim waves a bedcover in the midst of a cemetery in Greenpoint, Brooklyn; it is a moment that merges life with its apparent opponent, death. As such, the work suggests that the interpretation between existence and nonbeing may be forced; sometimes, a seeming dichotomy is actually two surfaces of a single idea. Kim's great strength as an artist is to find the moment wherein passion and calm, action and passivity, merge.

-

She would have us understand that art is the great equalizer of false dualities; our mind is a place capable of including most everything. In the generosity of her vision, Kim reiterates the great truths of the unknown, what lies above and beyond our lives. She takes what we implicitly know and bestows upon it a public grace. As she grows larger in her art, so do we, so completely are we included in her generous expanse of her imagination.

— From Art AsiaPacific, Fall 2003. * All quotations are taken from a written interview with the artist in Summer 2002.

- Jonathan Goodman is a poet, an editor, teacher, and writer who specializes in contemporary Asian art. He is the New York editorial adviser to Art Asia Pacific.

Cities on the Move - 2727 Kilometers Bottari Truck, 1997, 7:03 video loop, Silent.

Cities on the Move - 2727 Kilometers Bottari Truck, 1997, 7:03 video loop, Silent.

An Incantation to Presence

2003

- "The body itself is the most complicated bundle." — Kim Sooja

I. Sewing beyond space and time

-

Since the 1980s, between thread and needle, Kim Sooja's work has been developing; from Korea to New York, via Paris and a number of other cities across the different continents, like an avowed metaphor of the act of sewing. But it is less a question of sewing as such than linking up and uniting fragments of varied realities that were previously disparate. From her first works, with pieces laid end to end and sewn together, like a sort of collage involving both hand, body and mind in relation to matter, up to the recent videos of A Needle Woman, where the artist herself becomes a needle and integrates into the urban fabric, sewing has been the guiding thread in a subtle research project from which a language has evolved, and where a unique commitment can be read, with references that are first of all local, but whose scope has become global.

-

Over the course of time, Kim Sooja went from matter and the plane of the painting to the conquest of a liberating third dimension, and this allowed her to acquire greater mobility with the works entitled Bottari. In her videos and performances, her language subsequently became ever more economical, pursuing as though by incursion the possibility of the emergence of her oeuvre. The artist would like to be a needle that leaves no mark, that sews and disappears after closing the wound; after joining two bits of cloth, two continents or states of consciousness. Her discretion is consubstantial with her research, and her self-effacement facilitates revelation: to the appearance of the other, and to his presence. This path starts out from an approach to textiles, and a practice, that are rooted in Korean tradition but go beyond these local references through a language which is that of wandering, exchange and openness to the other, the unknown.

-

Kim Sooja's training as a painter predisposed her to consider the plane surface of the canvas as a field of exploration. Her first compositions were formal, based on grids and interlinking motifs. She had a penchant for the art of the 20th-century avant-gardes, and notably Mondrian, both in her practice and in the theoretical spirit that informed all her work. But the physical dimension of her sewn canvases dominated her work. The very act of making a picture with pieces of fabric became predominant, and this opened the way to gestures that were simpler, though just as emblematic.

-

Sewing thus became the essential element of her artistic process in the 1980s, to the point where it overshadowed pictorial considerations as such, and introduced the emotional charge that she had discovered while sewing by her mother's side. The act of sewing is one of intimacy, of withdrawing into oneself, close to symbiosis with a state of being that represents both tradition and family memory. This activity — almost passive, enthralling — locks the artist into a sequence of slow movements that repeat to infinity and are conducive to meditation. It is to be one with oneself, the fact of saturating oneself in one's own history. And the blankets made by Kim Sooja and her mother brought together two worlds that had previously been dissociated: the ancestral Korean tradition and her own pictorial quest.

-

Kim Sooja's first works were an introspection turned towards herself, and a way of calling herself into question so as to become a totality. In this sense, the action she accomplished could be seen as the denouement of the self. Skein, bobbin or hank: the thread has to be unwound.

-

The process begins with choosing pieces of cloth. To collect different textiles is to recompose one's being as one would reconstruct the fragments of a past: bits of individual stories that are becoming a new wholeness. The assemblage of these lacerations retains the marks and stigmata of the bodies that have borne them, with their dreams and daily sufferings. These recomposed entities become offerings, surrogates through which the memory of the other can act.

-

To salvage materials, assemble them, and sew them together is an intoxicating, almost ecstatic act of patience and repetition (from immobility to rapture). By the monotony of the gesture, this process makes it possible, also, to create a void within oneself — a void which can become a plenitude. For Kim Sooja, a work like Portrait of Yourself (1990-1991) is a solitary confession, an incessant and infinite conversation with oneself. The process is as important as the result. The production of this particular work is something like a meditation, and if one approaches it with the required intimacy it becomes a mandala. Iso it is both a self-portrait and a profound expression, a communication of the artist's humours, which shows how she carried out an apprenticeship on herself, how she matured through experiencing the passage of time and stepping aside from its onward movement. Despite the repetition of a movement that could become tiresome, the artist claims to have derived a great deal of energy from the experience. Through it she renewed her resources, as is suggested by the title of a work dating from this period, Towards the Mother Earth (1990-1991).

-

The back-and-forth movement of the needle through the material, from front to back, again and again, ended up by going beyond the plane surface, surreptitiously opening up towards a third dimension. Applying a reductionist logic to her work, Kim Sooja began covering objects with fabric, and thereby conquering space.

-

At the beginning of the 1990s came the first constructions of this order (Untitled, 1991). Two hoops connected by rods made the shift from the line to the third dimension. These constructions were then enveloped in pieces of fabric as a way of freeing them from the wall (which indicated a transition in the oeuvre), and from the plane surface of the painting, without giving up the symbolic charge of the first sewn works. For a time, the artist moved away from the act of sewing, strictly speaking, and transposed her metaphor into the simple act of covering objects.

II. Enveloping memory

-

Always seeking greater simplicity, Kim Sooja has rendered this emancipating act more radical still over the last decade, with works which now constitute, in a way, her signature: the bundles entitled Bottari.

-

The first of these date from 1992. They were created in the Open Studio at the P.S.1 (a contemporary art centre in New York, now associated with MOMA), and came into being, according to the artist, spontaneously, unrelated to any particular consciousness of things. But though nothing anticipated the event, everything announced the simplification of the procedure that had already been set up, in the direction of its essence and its highest degree of efficacy, with the abolition of all artifice, accessory or substrate in favour of the fabric alone. Cloth became the content and the container of the work, its structure and its surface, inside and outside. The Bottari provided an aesthetic solution to the question of the surface by stepping outside it, with a structure which was both open and closed; which revealed and concealed at the same time.

-

The bundle corresponds as much to a reference within the Korean tradition as to a universal metaphor of displacement, or even adventure, and a Bottari can hold all an individual's belongings. Originally, the custom was to use still-serviceable scraps of bright-coloured, precious silk from worn-out clothing, something of which was thus preserved.

-

In Korea, fabrics are traditionally used for multiple common functions such as storing bedding and clothing, or moving it around, notably when it has to be washed, as well as transporting food, or even wrapping gifts. For Koreans, the Bottari is both intimate and familiar, and is used on a daily basis. It is a sign of time-honoured aesthetic refinement, and is often an object of great value. It carries a strong affective charge, and is passed down from generation to generation.

-

It is symptomatic that Kim Sooja first explored the Bottari's possibilities while living outside Korea. She marked her return from her memorable stay at the P.S.1, where she had been a guest artist, with a Bottari installation in an abandoned house in Kyunju (1994). Bottari symbolize, in a way, the migrant who can put all his material goods in a bundle and be ready to set off at any moment. So when she came back and placed her bundles on a floor, Kim Sooja was reclaiming the space, but she was also indicating her readiness for an imminent departure. The inclination to travel is constant, or even necessary, when one has been elsewhere.

-

The "elsewhere" through which the artist found herself confronted with another perception of woman remains implicit as an underlying theme in her work: the body is torn between the modern Western world and her Eastern ancestral universe. This ambivalence would be irreconcilable if travelling did not offer a possibility of agreement between two different universes, in their alternation.

-

The resulting tension, which is latent in all her work, was laid bare by an installation, Deductive Object / Dedicated to my Neighbors, presented at Nagoya in 1996, where two forms amongst her productions were brought together in the exhibition space. For the first time, Kim Sooja made a contrast between the placing of the bundles and an arrangement of Korean bedspreads on the floor.

-

These are often given as presents to accompany a bride's trousseau, and are one of a household's most treasured possessions. In their folds they silently attest to the history of the couple. The motifs are symbolic references and exhortations to a happy life full of love, children and health.

-

Between the revelation of the bedspreads' symbolic motifs and the mystery of the bundles, with the precious contents that can be imagined, there is a tension which is all the stronger when one realizes the particular importance of the traditional bedspread in the Korean context; and it goes beyond a purely formal interpretation of the opposition between the flat surface of the bedspreads and the sculptural dimension of the bundles. The installation thus makes it possible to appreciate, simultaneously, the unveiling of a private life and the intensity of a retreat into oneself.

-

The bedspread is a witness-object whose day-to-day contact everyone can feel, It accompanies love, sex, dreams, nightmares, childbirth... and finally, at the moment of death, it becomes a shroud. So this envelope is a sort of skin, carrying in its folds what could be considered as a sort of portrait of its owner(s). Folded onto itself as a Bottari, the bedspread gathers up intimate possessions and protects them from inquisitive eyes. Opened out, it gives itself up in its flatness, and suggests the dreams that are incorporated into its traditional motifs.

-

In this sense, the Nagoya installation, so simple and pure in its expression, contained an entire mode of thinking about time, and the cycle of life and death. Later, exploiting the charged nature of such references, the artist used the bedspreads by themselves in various situations, as restaurant tablecloths and lines stretched out for washing to be hung on. With each installation, the visitor's participation is decisive, since it is up to him to activate the mechanism. In the case of a tablecloth, it is the actual use of the table by the visitor, in a museum restaurant, that makes the work exist. In the Korean context, this almost-reverse use of the bedspread as a tablecloth is of the order of the transgression, since tradition prohibits eating in the place where one sleeps. For the duration of a meal, the tablecloth is an integral part of the table companions' life. It is imprinted with the stains they leave, the traces of this slice of existence that it will have subtly transformed by its presence.

-

As in most of Kim Sooja's other installations, the onlooker is thus a protagonist — a constitutive element of the space in question. When he moves around to look at the work from different viewpoints, it is renewed at each step. Pursuing this logic so as to extend it ever further, in a recent presentation of the Laundry installations at the Peter Blum gallery in New York, A Mirror Woman (2002) had mirrors on all the walls with lines stretched out for hanging up washing. The spectator's contemplation of the work was eroded by his discovery of himself in the mirrors, which projected the field of the work into an infinite space. This visual confrontation with oneself is a curious, singular fact in a work that is characterized rather by the inconspicuousness of the artist in the interest of internalized reflection. In general, when a figure appears in her work (and in her more recent videos it is often herself), it has its back turned, as if to suggest a presence, but not a particular individuality. This is the case, for example, in the video of her performance Cities on the Move - 2727 Kilometers.

-

In November 1997, rejoining the nomadic life of contemporary artists, the better to in order to better reinforce it (but also enlarging the field of action of her work and its semantic purview), Kim Sooja decided to take her bundles on the road. She spent eleven days going round towns and other places in Korea that held specific memories for her. This meant that her bundles were loaded with new content: the memory of her past history and travels. In the filmed performance she is seen from behind, hieratic and impassive, sitting above firmly-attached Bottari in a truck driving through ever-changing scenery.

-

The idea of moving around becomes a reality in this video, which combines, for the first time in such an obvious way, a sense of the intimate and with a public dimension. The artist's silhouette, in its sobriety and black clothes, unlike the Bottari with their vivid, varied colours, stands up straight, like a needle.

-

The fact that she presents us only her back is a procedure that challenges us and thrusts us into the middle of the landscape. As in Caspar David Friedrich's romantic paintings, the silhouette of a back becomes our bodily referent, and we project onto it. This transfer gives extra substance to the work, and confers on it a shape for us, so that we become the subject. (The phenomenon is clearer still in the later videos of towns, which this performance adumbrates). Perched high up on the bundles, while the road goes by, the needle-woman both cuts through the landscape and sews it up again, the way a wound closes up. Finally, this Calvary of memory is a way for Kim Sooja to forge a link with her history and re-inject an emotional charge into her itinerary. So the Bottari that she takes round with her are phantoms of time gone by, to which this itinerary pays tribute. Each of them can be related to a person, and the journey takes on the character of a pilgrimage in honour of dear, loved beings.

-

This dimension of personal ritual was transcended when the artist presented her Bottari Truck in major festivals of contemporary art. What was of the order of the intimate then took on a universal, even denunciatory dimension with regard to its context.

-

She has taken part in the biennials which are the focal points of artistic nomadism: São Paulo (the 24th, in 1998), Venice (the 48th, in 1999), and Lyon (the 5th, in 2000). Arriving as in a bazaar upon which groups from different regions converge to exchange merchandise and cultures, the truck filled with Bottari of every colour accentuates the idea of displacement at the very moment when the international press is taking an interest in the situation of populations forced into exile across the world. But if Kim Sooja's installation can express displacement as a positive value, a search for a new paradise, it cannot cancel out the premises that any change of place is firstly seen as the breakup of a unity that has been lost forever. Displacement always implies cutting oneself off from one's birthplace and ancestral roots. There are voluntary exiles who have struck it lucky and found a better life. But deep in the soul of the uprooted person there is always a secret, persistent wound.

-

The historical context of the Bottari Truck cannot fail to recall the atrocities committed at the time of its creation in the Balkans, Africa and the Near East (to mention only those that made the headlines).

-

It is often never-ending struggles, and more rarely natural disasters, that force entire populations to pack up their bundles and set out from home, into the unknown. The Bottari, with their shimmering colours, convey all these paradoxical feelings, which are stirring memories but also as well as deep wounds.

III. The simultaneous elsewhere

-

Following the thread of her wanderings, Kim Sooja's recent series of videos are both at once subtle in their poetry, strong in their presentation, and complex in their social implications. They are grouped together by generic title. A Needle Woman alludes to her desire to disappear like a needle in a haystack, but also to be the needle that insinuates itself into the urban fabric. These performances, and the ones that derive from them, like A Beggar Woman, were presented for the first time in a solo exhibition at P.S.1 in 2001.

-

A Needle Woman (1999-2001) is a set of eight videos projected simultaneously on the four walls of a room. Each shows Kim Sooja from behind, dressed identically in the most neutral possible way, immobile, facing the human wave that is rushing round her in a busy street in one of the world's most populous cities: New York, Tokyo, London, Mexico City, Cairo, Delhi, Shanghai and Lagos.

-

The artist transports us into cities in every continent by taking them into a place where we become active participants. The large-format projections bring us face to face with life-size people, justifying a total immersion in the space of the work. The artist's back — as we said above — allows us to pass through into the work, into the depths of metropolises, and to narrowly avoid the abyss. This illustrates, more or less, the Kantian definition of the sublime: to feel an emotion through the devices the artist offers us as she opens up her own experience so that we can enter into it without risk or peril. The unobtrusiveness of the artist, in spite of her presence, could produce a multitude of approaches in which individuality would give way to the essence of our own thinking.

-

Kim Sooja's discretion eliminates every psychological aspect of the ordeal she has taken on. The whole point is what occurs around her, which appears as a catalyst. Taking our place in this installation, we realizse what is intimate and personal about the ordeal, for anyone who goes through it. Evidently the physical side of it begins with a meditation that leads to a sort of ecstasy. And in this sense, the artist, as an individual, is outside herself. She abstracts herself and becomes like a keyhole, or a negative image of herself, which makes perception possible for us.

-

Her interest in the elsewhere makes her central to the generation of migratory artists who, at the dawn of the new millenium, are questioning the limits of globalization. As an artist, she is invited to present her work in cultural institutions around the globe, while the art world has gone beyond the rich countries — where there are people who take an interest in such creative activity — to include less favoured countries. The result is that artistic discourse is becomes enriched by other voices, and the circulation of works finds new perspectives.

-

The simultaneity of her presence in these no more than a hunch: distant though they are from one another, and different as the historical and economic contexts may be, apart from their urbanistic and architectural characteristics, these cities are alike in the steady streams of individuals people going about their business, moving towards an inevitable meeting with their destiny. And so a continuum of races and peoples finds itself virtually at the center of the space. Simultaneity of presentation makes the common features of the beings in movement in these eight videos obvious at a glance. Only an attentive eye will be able to discern what differentiates them.

-

While the time of the work is acting on us, our body replaces that of the artist, and becomes the needle that leads the guiding thread. A Needle Woman, as Kim Sooja likes to define herself, weaves, as much as she rends, the urban fabric. The fine needle pierces the world, but the whole universe passes through the eye of the needle. In certain contexts, in spite of her self-effacement, the artist cannot escape her otherness: she is the foreigner, the observer, the element that can split apart as well as bind together. In fact she cuts the human flow, which has to pass around her, avoid her like an obstacle, open up before her. The specificity of each particular population appears in this encounter. And the encounter is the indicator of the specificity.

-

The characteristics of towns come out through contrast, according to what opposes them. Each possesses a distinct rhythm that is demonstrated by the perfect immobility of the artist as an immutable reference. Her proper time seems to be in suspension, while the rest of the town swirls round her. Kim Sooja's passivity is a source of worry and tension. One expects something to happen: an intrusion, something violent... Possible violence, like a specter haunting life in these metropolises at every moment.

-

The reactions of the passers-by (or their total absence of reaction) are archetypes of the imaginative profile that a given city suggests. And thus, without wanting to paint a sociological portrait, the videos comprise a number of elements that make it possible to characterize the people and their surroundings: their clothes, their way of occupying the street, their attitude in urban space... For example, passers-by in New York, London and Tokyo are distinguished by their rapid, determined gait. They have an objective, and their walk is a "power walk": they are efficacious, and scarcely notice the artist's presence. They have an individual goal, outside the range of the camera, in the direction of a horizon that protects them and immunizes them against everything that could deflect them from their path. Their life is traced out, and there is no place for the unexpected. The street is only a vector, and not a place of sociability.

-

In these cosmopolitan cities, all racial differences seem to fade. The artist goes almost unnoticed, and her features do not mark her out in places where there are people of all origins, and where hybrids are common. Modernity asserts itself here as an exacerbation of individuality, a sort of autism that tends towards homogeneity. Such cities are so full of stimuli and diverse fantasies that the intervention of an artist attracts little attention.

-

In places like Cairo, Delhi, Mexico, and especially Lagos, on the other hand, there is a tension between the modern and the traditional which means that existence is highly charged. The individual finds his full dimensions in an open space where he is attentive to those around him, because he seeks to evaluate his position and rank in the immense gamut of social classes and traditional hierarchies that are an essential part of these cultures.

-

The members of different castes and social classes mix in the street. They are wary of one another; they keep an eye on one another and expose themselves to situations in which there is always tension. Here, the street becomes a place of both coexistence and distinctions.

-

In these cities where the contrasts are strong, individuals want to assert themselves across the cleavages. They look at one another so as to make comparisons between one another, and every look contains a question (Am I from the same class or not? How am I to position myself, and where, in such a wide spectrum?); so it is not surprising that these are the cities where the immobile presence of Kim Sooja gets garners the most reactions. They are still preserved from blasé mundanity, and the artist stands out more strongly as a stranger. But it is above all her passivity and her determination to abstract herself that arouse curiosity, along with a desire to make her react, to draw her out of herself, so as to bring her back to everyday life and the flux of the community. In all these cities, it is the ever-present children who are the least hesitant about teasing the artist and turning her performance into a game.

-

The virtual meeting-point of eight streets in a unique space plunges us into the improbable river of the human continuum. Engulfed in the multitude, the artist is invisible, as she often aspires to being. This takes her work beyond the nature-culture cleavage, or the opposition of the contemporary urban to original nature. In natural settings, as in the performance A Needle Woman / Kitakyushu (1999), where she is stretched out on a rock, or in A Laundry Woman / Yamuna River, India (2000), where she is facing the river in question, she strives for the same contemplative detachment as in urban settings. Perhaps her deepest desire is to reconcile perfect immobility and perpetual motion. And is this not what she seems to be seeking when she indicates her wish to disappear for an entire month, as she dreamt of doing during the last Whitney Biennial? Is there not a paradox in the fact of wanting to be simultaneously everywhere and nowhere?

-

Kim Sooja embodies the complexity of the kind of globalization which both proclaims and denies the local spirit. Her work with textiles had a specificity that was linked to the Korean context of her origins. This opened up in the course of her peregrinations, gaining in breadth without cutting itself off from its roots, or disowning them. Her videos combine nature and the urban, the individual and the collective, the global and the local. The richness of her approach, in its discretion and subtlety, lies no doubt in her unique way of transcending divisions and resolving them in works that place the spectator at the heart of an extreme questioning process, which for each individual becomes personal and intimate.

— From the exhibition catalogue of Kimsooja: Conditions of Humanity, Contemporary Art Museum, Lyon, 2003:

- Julian Zugazagoitia is the Director of El Museo del Barrio in New York which is the foremost cultural institution for Latinos in New York. Prior to this engagement he was the Executive Assistant to the Guggenheim Museum Director where, among other projects he curated the exhibition Brazil: Body and Soul. He received his Ph.D in Aesthetics from the Sorbonne and graduated in art history from the Ecole du Louvre, Paris. H e was involved with the Getty for 8 years developing conservation and cultural projects in Benin, Egypt, Yemen, Italy and Spain. He was also responsible for establishing a long-term collaboration with UNESCO and curating the traveling exhibition Nefertari Light of Egypt that drew over a million visitors. As independent curator, he was responsible for the 1997 presentation of Mexican 20th-century art in Naples, the exhibition Pasione per la Vita and was the artistic director for exhibitions for the Spoleto Festival in Italy. In 2002 he was guest curator of the 25th Sao Paolo Biennial, where he curated the New York section. His recent publication, L'oeuvre d'art Totale, Gallimard, Paris 2003, a collective book on the Total Work of Art, springs from his Ph.D thesis and a lecture series organized with Jean Galard, presented at the Louvre and Guggenheim museums in 2002.

Encounter - Looking into Sewing, 1998/2002, digital c-print.

Photo by Lee Jong Soo.

Encounter - Looking into Sewing, 1998/2002, digital c-print.

Photo by Lee Jong Soo.

Kim Sooja: Being and Sewing

Maria Brewinska (Curator at Contemporary Art Center in Warsaw)

2003

-

The trace of a body. Not long ago, maybe just a while ago, there was a body here. It lived in a rhythm of everyday behaviour and actions, shaping the values and sense requisite to the existence of the objects surrounding it; clothes above all, the obvious, but usually trivialized signs of life, which remain in the body's place, in the place vacated by it, empty and useless. The independent existence of clothes, alongside the body's life, begins at birth, starting with little baby clothes and moving on to bigger and bigger ones. Clothes — there are always some bodies putting them on, wearing them, desiring them, striving to get them, taking possession of them, discarding, storing, inheriting. Nearly all their life bodies never part with what clothes, adorns and protects them, what is closest to them, next to the skin, what absorbs its smell, grime and sweat.

-

The objects left by the body, the clothes saturated with its physicality — are they not the most obvious and tangible traces of its reality, the proof of its existence? Is the material world coexisting with the body not its most faithful memory? The sense of this world disappears with the passing of a particular life, although it can be reborn with the life of new bodies. One moment, a freeze frame of the stream of life changes forever the state of the subject and object. It is maybe the most strongly felt — physically and psychically — end of the stream of the time of life, flowing in between, in space and time..

-

Kim Sooja: "We are wrapped in cotton cloth at birth, we wear it until we die, and we are again wrapped in it for burial. Especially in Korea, we use cloth as a symbolic material on important occasions such as coming of age ceremonies, weddings, funerals, and rites for ancestors. Therefore cloth is thought to be more than a material, being identified with the body - that is, as a container for the spirit. When a person dies, his family burns the clothes and sheets he used. This may have the symbolic meaning of sending his body and spirit to the sky, the world of the sky, the world of the unknown."

-

Scattered clothes and bottari, bundles stuffed with clothes, made of traditional Korean fabrics, are spread on the ground in a forest during the First Biennial in Kwangju in 1995. This installation, made of 2.5 tonnes of second-hand clothes and entitled Sewing into Walking was dedicated by Kim Sooja to the victims of the suppression of a democratic protest in Kwangju in 1980. The tragedy of those victims was expressed by an installation made of a mass of used clothes, those most obvious signs of the presence of a body.

-

Kim Sooja, e-mail, April 1, 2003:

-

The Kwangju Massacre happened in the 1980 and hundreds of people died for their democracy movement. When I was invited from Kwangju, I couldn't do anything before I commemorate their lives...

-

Deductive Object-dedicated to my neighbours was done in 1996 when the department store was completely collapsed and killed hundreds of people and I was in that building with my son 30 mins before collapse, and we used to live in the same block. I had to comment and commemorate the victims of my neighbours especially when I had an occasion to install my piece in Japan which had a lot to do with Korea in the history (war, colonization, conflict ...). So the neighbour means both my own neighbour in Seoul but also Korea-Japan relationship, so I mixed the Korean used clothes with Japanese.

-

Kwangju, Seoul and Kosovo are just a few of the many places in the world which have been marked forever by the death of many beings. Kim Sooja sees it, but she does not get involved in political conflicts. So when she presents Bottari Truck — in Exile, a truck loaded with colourful bottari, at the Venice biennial and dedicates that event to the [victims of] the war going on at the same time in Kosovo (so close to Venice), that gesture is just an expression of concern for the lot of other people.

-

Kim Sooja conceptualizes political events through installations in which an important element are bottari and traditional Korean bedcovers, objects strongly associated with women and the roles they play (in Korea considerably limited by Confucianism). Another key element of the installation are used clothes, which in Korean tradition are carriers of the spiritual element, and in Kim Sooja's works also become a representation of the human body. Those are, it seems, the only three projects with implied political, social and emotional meanings; all the others are creative acts made concrete as objects, installations, performances and videos; recently, those are becoming increasingly minimalist. An attitude of conscious "inaction" is articulated ever more plainly in the performances realized and registered on video in different places around the world and shown in exhibition rooms.

-

In an essay published in this catalogue Adam Szymczyk proposes a new interpretation of the artist's work. Giving descriptions of journalist's reports of the war in Iraq, he confronts Kim's quiet presence with the media clamour accompanying the current political situation in the world. Kim Sooja's media personality is radically different from the way the media operate. In her video performances she shows her body, but remains silent and conceals her face, turning away from the viewers. She seems to be protesting against the noise made by the media and against all acts directed against human beings, including accidental tragedies (such as the collapse of the supermarket in Seoul), expressing her opposition to the pain and suffering accumulated in the clothes.

-

Kim Sooja consciously cultivates this attitude by a contemplative perception of the world and a rejection of excess information (e.g. deciding not to read books). She is a nomadic artist, constantly on the move, but she seems to stand firmly on the ground. In fact, her attitude may be interpreted, in a simplified way, as a practical exemplification of Heidegger's being-in-the-world, an existence cast into the world, but conscious of its "spatiality"; concerned, but not frightened; a being open to cognition and "the world's worldliness"; a being which accepts other "beings".

-

Kim Sooja: "When I look back over my more than twenty years of handling bedcovers, I feel that I have always been performing, guided by the piles of cloth I haved live among. What in the world have I stitched and patched. What have I tied up in bundles. When will the journey of my needle end, my silkworm unwrap its flesh. Will it in the end slough off its skin. Will the boundless with no destinations find theirs ways to go."

-

Looking at the twenty years of Kim Sooja's work we can see that they form a consistent process. After art studies in Seoul, until about 1992, Kim Sooja makes abstract collage using traditional Korean fabrics and clothes. She combines sewing as a technique with drawing and painting. In those pieces sewing becomes not only a direct way of creating form, but a constitutive element defining her work. The use of this unique technique, associated rather with gender art, women's art, is blends with the artist's personal experience, taken from her family home, of sewing the traditional bedspreads together with her mother and grandmother. She sews her first objects from inherited clothes and bedspreads.

-