2013

셀린 웬트 │ 바느질을 삶으로

2013

Selene Wendt │ Sewing into Life

2013

David Morgan │ Kimsooja and the Art of Place

2013

Mary Jane Jacob │ Essential Empathy

2013

Steven Henry Madoff │ Gnomon of Place, Gnomon of Foreignness

2013

한행길 │ 삼라만상을 하나로 묶는 김수자의 보따리

2013

Kostas Prapoglou │ 55th Venice Biennale: Il Palazzo Enciclopedico | The Encyclopedic Palace

2013

Seungduk Kim │ Centripetal Acceleration

바느질을 삶으로

2013

-

예술가는 하나의 고립된 체계가 아니다. 살아남기 위해 그는 자신을 둘러싼 세계와 끊임없이 상호작용해야 한다. (…) 이론적으로 예술가의 개입에는 제한이 없다. – 한스 하케(Hans Haacke)

-

자신을 둘러싼 세계와 상호작용하는 일, 그것이 김수자가 자신의 작업을 통해 수행해 온 일이다. 1980년대 초반부터 그는 예술과 삶의 직접적 관계와 그 상호작용을 표현하는 수단으로 (말 그대로 그리고 은유적으로) 바늘의 힘에 기대어 왔다. 이것은 김수자의 작업 전체를 꿰는 금빛 실이다. 작가는 서울에서 회화를 전공하고 파리에서 단기간 판화 연수를 받았으나, 붓과 캔버스 대신 바늘과 천이 지닌 독특한 가능성에 주목했다. 어린 시절 어머니와 함께 침대보를 꿰매던 경험을 통해, 그는 천이 강력한 예술적 매체가 될 수 있음을 인식하게 되었다. 바늘로 천의 표면을 꿰매는 행위를 통해 그는 자유롭게 사유할 수 있었고, 이 천이라는 비유 안에 철학, 예술적 과정, 역사가 모두 수렴되는 듯했다.

-

김수자가 처음 바느질을 시작했을 때, 그는 회화의 한정된 표면 너머로 가기 위해 그 반대편에 도달하고자 했다. 작가는 바늘을 통해 천의 막 속으로, 그리고 그 너머로 나아간다는 생각에 매료되었다. 이어서 그는 실로 천을 감싸는 행위로서 바느질이 가지는 의의를 생각했다. 김수자는 반복되는 의식과 같이 오가는 바느질의 움직임과 그것에 내재한 창조적이고 (보수한다는 의미에서의) 치유적인 목적에 흥미를 느꼈다. 처음부터 김수자는 바느질로 꿰매어지는 대상에서 자신을 보았으며, 이는 곧 자아의 확장을 의미했다. 바늘과 실을 쥔 손이 정교하고 단조로운 수공의 동작을 반복하는 동안, 생각은 멀리 자유롭게 떠돌게 된다. 다시 말해, 김수자는 삶 속에 의미를 꿰매어 넣는 것의 가능성을 발견했던 것이다.

-

처음부터 김수자의 작업에 있어 전통 한국 천의 문화적 의미는 핵심적인 요소였다. 그의 작업 전반에 사용된 천은 수많은 개인적 이야기의 강력한 흔적으로, 이 이야기가 한 데 취합되었을 때 그것은 인류 전체의 궁극적인 상호연결성을 제시한다. 천의 형식적 구조, 그리고 그 표면을 가로지르는 바늘과 실의 의미에 대한 김수자의 관심은 천과 나누는 무언의 대화로 나타나며, 이 대화는 공예와 전통적인 여성의 역할에 관한 쟁점을 탐구하는 일과도 관계가 있다. 김수자의 초기 작업은 대부분 콜라주와 유사한 기법을 이용한 작품이 많아 개념적이기보다는 형식적인 것에 중점을 두고 있었다. 섬세하게 꿰매어진 초기 작업은 이후에 펼쳐질 중요한 요소를 암시하고 있었다. 예를 들어, 빨강·노랑·초록색 천 조각을 거칠게 꿰매 장식된 베이지색 티셔츠는 색채, 형태, 구성을 탐구한 작품이며, 여기 보이는 느슨한 실들과 미완성처럼 보이는 거친 마감에는 숨은 의미가 얽혀 있다. 고통, 상실, 취약성을 이야기하고자 하는 텍스타일 작업에 종종 패치워크, 퀼팅, 자수, 박음질이 사용되기도 하지만, 그의 작업에서 바느질(sewing)이라는 행위 자체는 목적이 아닌 표현의 방법이다. 시간이 지나면서 바느질에 대한 작가의 접근은 점점 더 개념적으로 변화했으며, 이후 작업에서 실과 천이라는 물질이 완전히 사라지는 것은 이전의 작업에서 시각적으로 화려한 텍스타일을 사용한 것만큼이나 중요한 의미를 지닌다. 은유로서의 바느질, 특히 바늘에 부여된 상징성은 정체성과 실존이라는 보편적 문제들과 맞닿아 있으며, 이는 김수자의 작업 전반을 하나로 깔끔하게 엮어내는 중요한 매개가 된다.

-

1990년대 초부터 시작된 <연역적 오브제> 연작은 일상 사물을 통해 삶의 이야기를 소통한다는 면에서 이후 작업의 중요한 단서가 된다. 이 연작에서 김수자는 연, 얼레, 삽, 포크, 창틀 등 문화적으로 특수한 일상 사물을 한국의 이불보와 옷감 조각으로 감싸며, 형식적·개념적 경계를 확장하는 작업을 선보였다. 이처럼 ‘이미 만들어진 사물(already-mades)’은 가정성과 여성의 노동과 깊이 연결된 것으로 풍부한 사회적, 문화적, 미학적 함의를 가진다. 김수자는 일상에서 찾을 수 있는 사물, 특히 이불보를 다루는 자신의 작업에서 그것이 ‘사전에 만들어진(pre-made)’ 것이 아니라 ‘사전에 사용된(pre-used)’ 것이라는 사실에 가장 큰 관심을 둔다고 강조한다. 또한 작업에 사용된 이불보의 역사는 그것을 바느질하여 만든 익명의 사람보다도 그것을 소유해 사용했던 사람과 연결되어있다는 점 또한 강조한다. 그가 사용하는 사물과 천이 지닌 영혼, 아우라, 기억은 영적·개념적 차원 모두에서 궁극적인 중요성을 지닌다.

-

김수자는 이후 <연역적 오브제> 연작의 맥락을 확장하여, 어떤 사물이 그 주변 공간과 맺는 관계에 초점을 맞추기 시작했다. 1993년, 그는 뉴욕의 PS1에서 중요한 전시에 참여했는데, 그중 한 설치 작업이 특히 눈에 띄었다. 그의 작업에서 종종 보이는 ‘복합적인 단순함’이 바로 그 작업을 강력하게 만드는 요소였다. 곳곳에 작은 구멍이 나 있는 하얗게 칠해진 거친 벽돌 벽을 상상해보자. 대부분의 예술가와 큐레이터들이 아마도 평평하게 만들거나 가리고 싶어 할 만한 그런 전시장 벽이다. 김수자는 개입으로서의 바느질이라는 개념을 아름답게 소개하는 제스처로 이 벽과 직접적으로 마주해 관계를 형성했다. 벽의 틈새 속, 그리고 작품의 천 조각들 사이사이에는 김수자의 작업이 나아가는 방향을 암시하는 중요한 단서가 담겨있었다. 그것은 바로 바느질을 삶으로(sewing into life) 여기는 개념이다. 벽면 곳곳에 끼어 있는 다채로운 천 조각은 바느질의 개념을 탐구한 결과다. 벽의 각 구멍은 마치 작은 천 조각이 바늘구멍에 꿰어진 듯한 모습이다. 일견 전체적인 작업의 패턴은 텍스타일 작업의 발전처럼 보이지만, 작품의 진정한 본질은 틈새 공간과 인류를 서로 이어주는 보이지 않는 실들이 만들어내는 연결에 있다. 물질보다는 은유에 초점을 맞춤으로써, 김수자는 실존적 문제에 관한 지속적 탐구의 과정을 드러내는 한편 텍스타일 및 바느질의 실천적 가능성을 수용하는 동시에 그것의 한계를 시험한다.

-

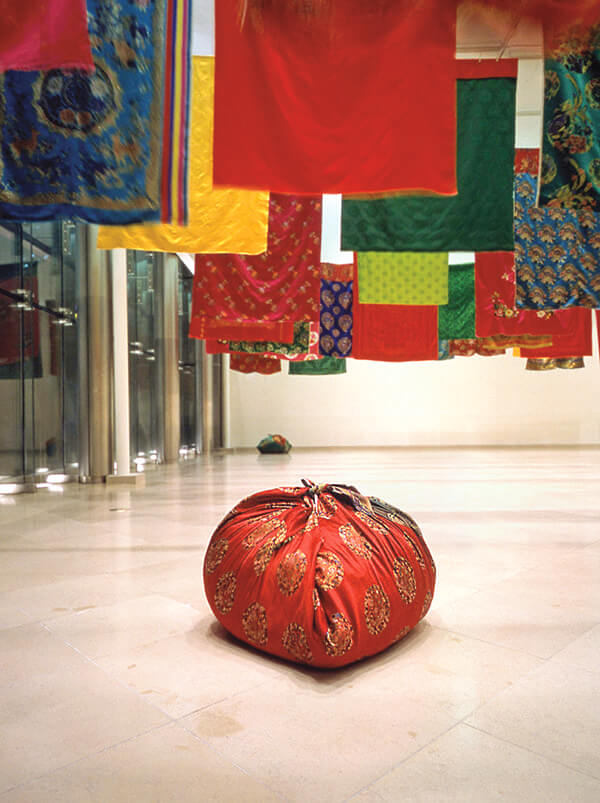

1990년대 초, 김수자가 보따리 작업을 만들기 시작하면서 예술과 삶을 하나로 엮는 개념적 문제가 한층 더 뚜렷하게 드러나기 시작했다. 이를 계기로 그의 작업은 완전히 새로운 차원으로 나아갔다. 김수자는 전통 한복천으로 만든 다채로운 색상의 보따리(소지품을 싸서 운반하는 한국의 전통적 방식)로 국제적인 주목을 받았다. 보따리는 일반적으로 어떤 천으로도 만들 수 있지만, 김수자는 신혼부부를 위해 제작되었다가 버려진 한국의 혼수 이불을 선택했고, 누군가가 사용했던 옷을 모아 그 안에 싸맸다. 이처럼 그의 <보따리> 작업에는 흥미로운 이중의 의미가 내포되어 있다. 김수자의 <보따리>는 한국의 전통에서 자신의 소유물을 감싸매는 관습과 직접적으로 연결된 예술 오브제로서 이동 혹은 이주를 암시하며, 개인적 의미를 지녔던 물건을 담고 있다는 점에서 실제로 ‘보따리’의 기능을 한다. 순수 형태와 기능 사이에 완벽한 균형을 이루는 그의 작품은 예술과 삶의 경계 위에 절묘하게 놓여있다. ‘보따리’에 대한 김수자의 관심은 곧 표면에 대한 회화적 탐구에서 조각적 물성으로의 관심으로 자연스럽게 전환되었다. 이 과정은 점차 더 추상적인 영역으로 나아가 바느질은 여러 공간과 환경이라는 맥락 속에서 간접적인 방식으로 나타났다. 즉, 김수자는 전통적인 의미의 바늘에서 자신의 사유를 시작했지만, 그는 의도적으로 이 물리적 바늘이 만드는 제약에서 벗어나고자 했다. 그리고 바느질의 과정을 해체함으로써, 결국 바늘, 실, 천과의 직접적 연결 관계가 거의 감지되지 않는 형태에 다다랐다. 궁극적으로 실제 바느질과 관련하여 남은 것은 바늘의 개념적 흔적, 혹은 자율권과 해방의 수단으로서 바늘이 가지는 은유적 의미뿐이다.

-

바늘과 실의 유무와 상관없이, 김수자는 바느질이라는 개념과 관계된 이야기와 예술을 통해 삶에 뿌리내린 매혹적인 이야기를 전한다. 예술적 과정으로서의 바느질, 조용한 사유 행위로서의 바느질, 천의 표면과 나누는 대화로서의 바느질, 형식적 탐구로서의 바느질, 명상의 과정으로서의 바느질, 여성의 전통적 성역할과 관련된 바느질, 공예로서의 바느질, 개입으로서의 바느질, 감싸는 행위로서의 바느질, 그리고 연결 행위로서의 바느질까지 이 모든 것은 김수자가 예술에 접근하는 독자적인 방법이라는 복잡한 직조 구조를 구성한다. 삶과 예술에 대한 성찰은 시공간을 자유자재로 드나드는 끝없는 실처럼 풀려나온다. 그리고 과거, 현재, 미래는 이 공간 안에서 하나로 융합된다.

-

김수자가 보따리를 통해 예술과 삶의 총체성을 효과적으로 표현할 수 있음을 자각하던 즈음, 수지 개블릭(Suzi Gablik) 역시 ‘접속의 미학(connective aesthetics)’에 대한 연구를 통해 유사한 주제를 탐구하고 있었다. 개블릭이 참여적이고, 공감적이며, 관계적인 참여 양식으로 설명한 것은 바로 김수자의 예술적 접근법을 규정하는 핵심 요소이다. 개블릭이 『미술의 매혹(The Reenchantment of Art)』에서 제시한 접속의 미학 이론은 마치 김수자의 예술 실천에 대한 헌사처럼 읽힌다. 예술이 세계 속 우리의 위치를 이해하도록 돕는 역할을 한다면, 사물의 역할을 넘어 우리의 현존과 진정 관계 맺을 수 있다면, 김수자의 접근법은 분명 개블릭이 추구했던 방향성을 띠고 있다. ‘마음 챙김(mindfulness)’, ‘의식(consciousness)’, ‘연민(compassion)’, 그리고 ‘공감(empathy)’은 개블릭의 글에 반복적으로 등장하는 단어이며, 김수자의 작업 또한 이러한 단어들과 관련이 있다. 그의 작업에는 여성적 접근을 포용하는 관계적 비전을 찾고자 했던 개블릭의 탐구가 분명 존재한다. 개블릭은 자신의 글에서 “과거 관점의 근간을 이루는 것이 관계적 감각이 아닌 모든 것이 대립한다는 감각이었다면, 현재 새롭게 떠오르는 세계관은 우리가 지각하는 것과의 합일로 접어들 것을 요구하여 연민의 눈으로 바라볼 수 있기를 촉구한다”라고 썼다. 이러한 맥락에서 20년이 지난 지금도 김수자의 예술은 여전히 연민의 시선과 유의미한 관점을 담고 있다.

-

돌이켜보면, 우리는 김수자의 예술 실천에서 일관된 재료와 접근법을 의식적이고 단호하게 사용해 온 유무형의 흔적을 발견하게 된다. 그러나 새로운 프로젝트 안에서 이 일관성은 다른 맥락을 지니며 새로운 층위의 의미를 촉발한다. 김수자의 작업이 빚어내는 정교한 패턴은 하나의 바늘에서 비롯된다. 이 바늘은 계속해서 안정적이면서도 유동적인 개념들을 가리키는 동시에 물질적이면서도 비물질적인 것, 가시적이면서 비가시적인 것, 단순하면서도 복합적인 것들을 끊임없이 향하고 있다. 루이즈 부르주아(Louise Bourgeois)는 섬유에 관해서 그것이 거미가 짠 것이든, 물레로 감아 만든 것이든 모두 깊은 의미를 지니며, 그 실이 우리 모두를 위해 중요한 기억과 감정적 연결을 엮어준다고 말한 바 있다. 이 말은 섬유로 구성된 직물 속에 영구히 각인된 이야기들, 즉 김수자에게 계속해서 예술적이고 영적인 영감을 주는 이야기에 대한 작가의 매혹을 정확히 포착하고 있다.

-

수년간 김수자의 <보따리> 작업은 세계 곳곳의 다양한 맥락 속에서 등장해 왔다. 그것은 마법처럼 그 어떤 전시 공간이나 자연환경에도 유려하게 스며든다. 노련한 세계 여행자처럼, 김수자의 <보따리>는 끊임없이 이동한다. 미술관이나 숲속에서 보따리는 홀로 혹은 군집을 이룬 형태로 놓여 있기도 하고, 정교하게 일렬로 놓이거나 다소 무질서하게 흩어져 있기도 하며, 완전히 정지해 있거나 트럭에 실려 2,727킬로미터를 이동하기도 한다. 시시각각 달라지는 이 형태는 그의 작업에 깊이를 더하고 또 의미를 펼쳐낸다.

-

<보따리>와 아름다운 대조를 이루는 또 다른 작업으로, 김수자는 천을 풀어내고, 펼치고, 바닥에 깔거나, 조심스럽게 어딘가에 걸어 놓은 반짝이고 생동감 있는 직물 설치 작업으로도 잘 알려져 있다. 강렬한 색채의 텍스타일 작업인 <빨래하는 여인 A Laundry Woman>(2000)은 이러한 작업의 완벽한 예시다. 설치 공간에 들어선 관객은 직물에 완전히 둘러 쌓이게 되며, 패턴과 의미가 만나게 되는 지점인 정교한 색의 그물망 속을 걸어 나아가도록 초대된다.

-

김수자는 종종 바느질과 걷기를 유사한 행위로 비유하며, 그 유사성을 처음 알아차리게 된 순간을 다음과 같이 설명했다. “1994년에 경주의 옥산서원 골짜기 부근에서 작업을 하던 매일의 과정을 다큐멘터리 영상으로 촬영했다. 이 영상을 보면서 바늘의 상징으로 나의 몸을 바라보게 되었다. 그리하여 이 영상을 <바느질하며 걷기 – 경주(Sewing into Walking - Kyungju)>(1994)라는 제목의 비디오 퍼포먼스 작업으로 만들기로 결정했다. 나는 내 몸이 바늘의 역할을 한다고 보고, 자연 속에서의 이 걷기의 과정이 상징적인 바느질 행위로써 모든 이불보를 수집하고 모으는 것을 발견했다.” 설치 작업 <빨래하는 여인> 사이를 거닐며 관통한다는 것은 직물이 가지는 본질적인 소통의 힘과 끝이 없는 것처럼 보이는 함의를 이해하는 일이다. 작가의 한 걸음마다, 바느질 한 땀마다, 관객은 작품의 형이상학적 차원을 이해하는 데 점점 더 가까워진다. 이때 관객 또한 아름다운 직물 사이사이를 거닐며 그것들이 지닌 이야기를 엮는 일종의 은유적 바늘이 된다. 특히 작가가 장식적인 한국의 이불보를 선택한 이유는 그것이 고통, 상실, 사랑, 욕망과 연결된 삶의 이야기를 담은 누군가의 친밀한 소유물이었기 때문이다. 이 직물들은 문화적, 개인적 역사가 스며든 서사로서, 그것을 마주한 관람자가 그것을 마주하고 풀어내 주기를 기다리고 있다. 예술과 공예의 세계 사이를 조심스레 오가면서 말이다.

-

김수자의 작업에서 각 프로젝트는 실로 이어지듯 다음 프로젝트와 불가분하게 엮여 있다. 프로젝트마다 개념적 실이 발생하고 다시 꿰매어져 복잡하게 상호 교차적인 현실이 형성된다. 그 완벽한 예로, <빨래하는 여인>과 <거울여인(A Mirror Woman)>(2002)의 유사점과 차이점에서 이러한 연결을 볼 수 있다. 두 작품은 형식적으로나 개념적으로 매우 유사해 보이며, 모두 폭넓은 실존적 문제와 관련된다. 그러나 벽 전체를 덮은 거울을 추가한 것만으로 두 작품은 큰 차이를 갖게 된다. 거울은 무한한 공간에 대한 감각을 강화한다. 관람자는 눈앞의 직접적인 현실에서 끝이 없는 공간으로 초점을 옮기게 되며, 이러한 감각은 개인보다는 우주와 관계된 초월적 공간에 대한 것으로 확장되는 것이다. 정교한 직물을 구성하는 실 가닥들이 서로 맞닿지 않더라도 동일한 직물 안에 엮여 있듯, 모든 실 가닥들이 전체적인 효과에 중요한 기여를 하게 된다. 이 두 작품은 같은 천에서 잘려 나온 두 개의 조각처럼, 우주 속에서 각 개인이 차지하는 위치를 상징적으로 나타낸다. 메시지는 차고 넘치게 분명하다. 바늘이 없다면 천도 없으며, 개인이 없다면 사회라는 직물도 존재하지 않는다.

-

바늘이 가장 추상적인 형태에 이르는 과정을 따라가다 보면, 바느질이 지닌 은유적 의미가 한층 더 분명해진다. 바늘은 신체의 연장으로 쉽게 이해될 수 있는데, 이는 2채널 영상 설치작품 <바늘여인(A Needle Woman)>(1999)에서 가장 명확하게 드러난다. 이 작품에서 바늘은 완전히 이론적인 방향으로 나아간다. 한쪽 화면에는 김수자가 다양한 도시의 거리 위에 정지한 채 서 있고, 다른 한쪽 화면에서는 거대한 바위 위에 누워 움직이지 않는다. 이 두 영상에서 나타나는 대조성은 그의 작업 전반에 걸쳐 나타나는 강력한 대화를 형성한다. 도쿄, 상하이, 델리의 번잡한 거리 속에서도 그의 역할은 변하지 않는다. 김수자는 홀로 바늘처럼 곧게 서 있다. 바늘을 상징하는 김수자는 자기 자신을 이용하여여 사회라는 직물을 꿰매고 있으며, 바늘이 그러하듯 일정한 때가 되면 잠시 사라진다. 반면 다른 화면에서는 자연의 한가운데 거대한 바위 위에 누워 있다. 빠르게 움직이는 도시 장면과는 대조적으로, 변화하는 것은 맑은 하늘 아래 떠가는 구름과 미세하게 달라지는 빛뿐이다. 이처럼 김수자는 두 개의 지점을 연결하고, 결국에는 사라지는 존재라는 점에서 바늘의 은유 그 자체이다. 그의 역할, 혹은 그의 신체가 수행하는 역할은 사회라는 직물과 상호작용하며 특정 방향으로 우리의 시선을 이끌고, 그 후 바늘이 제 역할을 마친 뒤 사라지듯 스스로 모습을 감추는 것이다.

-

<바늘여인>에서 신체는 삶이라는 직물 속의 바늘로 나타난다. 김수자는 이를 중요하게 다루며 다음과 같이 설명한다. “서로 다른 지리적·사회문화적 맥락 속에 놓이는 방법을 통해 내 신체의 이동성은 그것의 부동성을 나타내게 된다. 부동성은 이동성에 의해서만 드러나며, 그 반대 또한 마찬가지다. 퍼포먼스가 진행되는 동안 계속해서 이동하는 거리 위 사람들의 움직임과 그 자리가 원위치인 듯 부동의 자세로 존재하는 나의 신체 사이의 지속적인 상호작용이 작동한다. 이 상호작용은 그 사회, 사람들, 도시의 성격, 거리의 특성 등의 맥락에 의해 좌우된다. (…) 나는 내 신체와 외부 세계를 공간/신체 및 시간/의식과 연관된 ‘관계적 조건(relational condition)’ 속에 병치하는 방식으로 존재론적 질문을 제기한다.” 이 말은 김수자의 작업 전반에 나타나는 예술적 접근을 효과적으로 요약하며, 이는 궁극적으로 개인의 특이성이 끝없는 다중성의 일부라는 사유로 귀결된다. 김수자의 시선을 통해 세계를 바라볼 때, 우리는 바늘의 구멍을 통해 우주를 들여다보는 듯한 경험을 하게 된다. ‘삶을 꿰매어’ 가면서, 동시에 그는 자신의 작업의 개념적 근간을 이루는 실을 푼다. 작업의 가시적, 비가시적 이음새들에는 이주, 전쟁, 문화적 충돌의 흔적이 누군가의 정체성과 현실 인식에 필연적으로 영향을 미친다는 것이 내재되어 있다. 이는 접속의 미학의 힘을 명확히 인식하고 있는 예술가에 의해 전달된다. 예술과 삶의 총체성을 향한 그의 상상력은 봉합하고, 치유하며, 연결하는 상징적 힘으로서의 바늘을 통해 아름답게 전해진다. 김수자는 문자 그대로 또는 개념적인 실천으로서 바느질을 대하며 만든 여러 작업과 태도를 통해 우리를 자각과 이해의 영역으로 이끈다.

[Note]

[1] 김수자는 의도적으로 ‘레디메이드(readymade)’ 대신 ‘이미 만들어진 것(already-made)’이라는 용어를 사용한다.

[2] Suzi Gablik, The Reenchantment of Art, Thames and Hudson, NY, 1991. Page 130.

[3] 올리비아 샌드(Olivia Sand)와의 인터뷰, Asian Art Newspaper, 2002년.

[4] 키아라 지오반도(Chiara Giovando)와의 인터뷰, 2012년, 김수자 공식 웹사이트 게재. https://kimsooja.com/texts/the-unaltered-reality-of-the-world

- — 『김수자 – 펼침』, 2013년 도록 수록 글, 영한 번역(한국문화예술위원회 후원): 임서진

A Laundry Woman, 2000, used Korean bedcovers and clothing, dimensions variable, installation at the Kimsooja, A Needle Woman - A Woman Who Weaves the World, Rodin Gallery (Plateau Samsung Museum of Art)

A Laundry Woman, 2000, used Korean bedcovers and clothing, dimensions variable, installation at the Kimsooja, A Needle Woman - A Woman Who Weaves the World, Rodin Gallery (Plateau Samsung Museum of Art)

Sewing into Life

2013

-

An artist is not an isolated system. In order to survive he has to continuously interact with the world around him…Theoretically there are no limits to his involvement – Hans Haacke

-

Interacting with the world around her is precisely what Kimsooja does throughout her work. Since the early eighties, she has relied on the power of the needle, literally and metaphorically, as a means of expressing the direct interaction between art and life. This is the golden thread that binds her work together. Although educated as a painter in Seoul with a short printmaking scholarship in Paris, Kimsooja quickly discovered the unique possibilities associated with the use of needle and fabric as opposed to brush and canvas. She first discovered fabric as a powerful artistic medium, as a young girl, while sewing a bedcover with her mother. The act of stitching through the surface with a needle made her mind wander; philosophy, artistic process, and history all seemed to converge with the fabric.

-

When she first began sewing, Kimsooja wanted to overcome the limited surface of painting by reaching to the other side. She was drawn to the idea of getting in and beyond the membrane of cloth with a needle, and subsequently realized the significance of sewing as a process of wrapping fabric with threads. Kimsooja was intrigued by the continuous and mesmerizing back and forth action involved in sewing, and its inherent creative or mending purpose. From the outset, the process of sewing allowed her to identify herself with the object being sewn, which simultaneously represented an extension of the self. With needle and thread in hand, the mind can wander while the hand goes through the motions of a precise and monotonous craft. Quite simply, Kimsooja had discovered the possibility of sewing meaning into life.

-

From the start, the cultural relevance of traditional Korean cloths has been an integral aspect of Kimsooja’s work. The fabrics implemented throughout her work function as powerful traces of the countless personal stories that, when purposefully brought together, speak of the ultimate interconnectedness of all humanity. Her fascination with the formal structure of fabric and the implications of the needle and thread moving through its surface translate to a silent conversation with the fabric, one that also involves an investigation of issues related to craft and traditional women’s roles. Kimsooja’s earliest works involved collage-like techniques that were, for the most part, more formal than conceptual. These delicate, sewn works hinted at important aspects that would unfold in later work. For example, a plain beige t-shirt decorated with roughly sewn patches of red, yellow and green fragments of clothing comprises a study in color, form and composition, and an underlying meaning is woven into the loose threads and rough unfinished edges. While patchwork, quilting, needlework and stitching are implemented in textile works that speak of pain, loss and vulnerability, sewing itself is simply a means of expression, not the end goal. Through the years, Kimsooja’s approach to sewing has become increasingly conceptual; the complete absence of thread or fabric in some works is as important as the bright textiles featured in other works. The power of sewing as metaphor, and the symbolism associated with a sewing needle in particular, relate to universal issues of identity and existentialism that tie all of Kimsooja’s work neatly together.

-

Kimsooja’s Deductive Object series from the early nineties is also highly indicative of later developments in her work, particularly in terms of the possibilities associated with conveying life stories through common objects. For this series, Kimsooja made use of culturally specific everyday items, such as kites, reels, shovels, forks, or window frames that she wrapped with swatches of Korean bedcovers and clothes, in works that pushed formal and conceptual boundaries. These ‘already-mades’[1] are strongly linked to issues of domesticity and women’s labor, and are rich with social, cultural and aesthetic implications. In her work with found objects, and bedcovers in particular, Kimsooja stresses that she is most interested in the fact that the cloth or objects are ‘pre-used’ rather than ‘pre-made’. The history of the cloth as connected to its owner is underlined, rather than the significance of the anonymous person who may have sewn the bedcover in the first place. The soul, aura and memory of the objects and fabrics she uses are of utmost importance, both spiritually and conceptually.

-

Kimsooja subsequently widened the context of her Deductive Object series by placing emphasis on how the objects relate to the surrounding space. In 1993, she had an important exhibition at PS1 in New York, and one particular installation really stood out. As is so often the case with Kimsooja, ‘complex simplicity’ is precisely what makes the work so powerful. Imagine a white washed brick wall, scattered with small holes, the kind of exhibition wall that most artists and curators would want to smooth out or cover up. Kimsooja engaged directly with this wall, in a beautiful introduction to the idea of sewing as intervention. Hiding in the cracks of the wall, and nestled between the threads of the work, are some very important clues about the direction that Kimsooja’s work was taking – sewing into life. The colorful scraps of fabric scattered around the wall play with the concept of sewing, as each hole in the wall relates to the eye of a needle metaphorically threaded with tiny pieces of cloth. While the overall pattern echoes a textile work in progress, the true essence of the work lies in the space in between, in the connection between the invisible threads that join humanity together. By placing emphasis on metaphor rather than material, Kimsooja reveals the bare threads of her ongoing investigation of existential issues while simultaneously embracing and challenging the possibilities connected with textiles and the practice of sewing.

-

In the early nineties, Kimsooja started making bottari, and the underlying conceptual issues that bring art and life together became even more evident. This raised her work to an entirely new level. Kimsooja gained international recognition for these colorful fabric bundles made from traditional Korean cloths, used to wrap and carry one’s possessions. Although bottari can be made using any kind of fabric, Kimsooja intentionally uses abandoned Korean bedcovers made for newlyweds that she subsequently wraps around used clothing. As such, her use of bottari involves a fascinating double entendre. The bottari function as art objects that relate directly to the Korean tradition of wrapping ones possessions, conveying the idea of being on the move, while also functioning as real bottari that contain something of personal value. A perfect balance between pure form and function, they are beautifully situated on the boundary between art and life. Kimsooja’s interest in bottari also signaled a logical transition from a painterly interest in surface planes to the use of fabric as sculptural mass. This gradually led to a more abstract realm, where sewing is implied within the context of various spaces and environments. So, although she had started out with a traditional needle, Kimsooja freed herself from being bound by the needle by purposefully, yet almost imperceptibly, deconstructing the process of sewing, to the extent that the connection to a needle, thread or fabric eventually becomes barely discernable. Ultimately, all that is left in relation to real sewing are conceptual traces of the needle, or the metaphor of a needle as a tool of empowerment and liberation.

-

With or without a needle and thread, Kimsooja relays captivating stories through art that relates to life as it relates to the concept of sewing. Sewing as an artistic process, sewing as a quiet contemplative activity, sewing as a conversation with the surface of fabric, sewing as a formal investigation, sewing as a meditative process, sewing as it relates to traditional women’s roles, sewing as craft, sewing as intervention, sewing as wrapping, and sewing as a connective act, are all part of the complex fabric of Kimsooja’s singular artistic approach. Reflections about life and art are spun from a seemingly endless thread that weaves in and out of time and space, where past, present and future are melded into one.

-

Around the same time that Kimsooja realized that she could use bottari to effectively express the notion of the totality of art and life, Suzi Gablik was investigating similar themes in her research about connective aesthetics. What Gablik would describe as participative, empathetic and relational modalities of engagement are the defining factors of Kimsooja’s approach to art. Gablik’s theory of connective aesthetics, as outlined in her book The Reenchantment of Art, reads almost as an ode to Kimsooja’s artistic practice. If art should somehow help us to understand our place in the world, if art should work beyond its immediate role as an object and truly relate to our own existence, Kimsooja certainly provides the kind of approach that Gablik was interested in. Mindfulness, consciousness, compassion, and empathy are words that consistently appear in Gablik’s writing, and these words also come to mind in relation to Kimsooja’s practice. Gablik’s search for an enveloping relational vision that would embrace a feminine approach is definitely found in Kimsooja’s work. As Gablik writes, “The sense of everything being in opposition rather than in relation is the essence of the old point of view, whereas the world view that is now emerging demands that we enter into a union with what we perceive, so that we can see with the eyes of compassion.” [2] Twenty years later, Kimsooja’s art is as compassionate and relevant as ever.

-

In retrospect, we can see the visible and invisible traces of an artistic practice that has been consistently defined by a very conscious and determined use of the same materials or approach, set within different contexts where new layers of meaning emerge with each new project. The intricate pattern of Kimsooja’s work is created from a needle that keeps pointing towards concepts that are as fluid as they are static, simultaneously material and immaterial, visible and invisible, simple and complex. Louise Bourgeois once said that fibers, whether spun by spiders or created on a spinning wheel, have deep significance, and that threads weave important memories and emotional connections for us all. This truly captures the essence of Kimsooja’s fascination with the stories that are permanently imbedded in the fabrics that have provided an ongoing source of artistic and even spiritual inspiration for Kimsooja.

-

Through the years, Kimsooja’s bottari have appeared in many different contexts around the world, almost magical in the way they fit into almost any gallery space or natural environment. Like seasoned world travelers, Kimsooja’s bottari are constantly on the move; whether in a museum space or a forest, appearing in multitudes, or all alone, they have been arranged in a meticulously arranged row, or strewn about in a more chaotic manner, they have remained completely still, or moved 2727 kilometers on a truck. With each new setting, added depth and meaning unfolds.

-

In beautiful contrast to the bottari, Kimsooja is equally renowned for her textile installations where the bedcovers are unwrapped, unfolded, laid out, or carefully hung in gorgeous labyrinths of shiny, vibrant fabric. The vividly colored textile work A Laundry Woman, 2000, is a perfect example of this approach. On entering the installation, the viewer is completely surrounded by textiles and is invited to walk through an intricate web of color where pattern and meaning converge. Kimsooja has often compared sewing and walking as similar activities, and describes how this first came about, “In 1994, I started connecting my body as a symbol of a needle in the moment that I was viewing the documentary footage of my daily working process undertaken at Oksanseowon Valley near Kyungju, Korea. I decided to make this as a video performance piece called Sewing into Walking - Kyungju. I identified this walking process in nature—the collecting and gathering of all these bedcovers—as a symbolic needlework which my body was serving.” [3] To walk through A Laundry Woman is to understand the inherent communicative power of textiles, and the underlying meanings are seemingly endless. With each step, as with each stitch, the viewer is one step closer to understanding the metaphysical aspect of work. In this case, the viewer plays the metaphorical role of the needle, winding in and out, betwixt and between these gorgeous fabrics that have a story to tell. The specific choice of decorative Korean bedcovers as intimate possessions that tell life stories of pain, loss, love, and desire is, of course, as significant as ever. These fabrics, colored by cultural and personal histories, are narratives that are literally left hanging for the viewer to unravel as they delicately float between the worlds of art and craft.

-

In Kimsooja’s work, each project is inextricably bound to the thread of the next project. From project to project, the conceptual thread is picked up and re-sewn into a complex and interwoven vision of reality. A perfect example of this is seen in the similarities and differences between A Laundry Woman and A Mirror Woman, 2002. These works appear to be quite similar, both formally and conceptually, and they both relate to a wide range of existential issues; yet the simple addition of mirrors that cover the walls is all it takes to set these works dramatically apart. The mirrors contribute to a heightened sense of infinite space, thereby shifting the focus from the immediate reality of the viewer’s experience to an endless space that can be understood as relating more to the universe than the individual. Similar to separate threads in an intricate piece of fabric, even if they don’t touch each other, they are still bound to the same fabric, and every single thread plays an equally important role in contributing to the overall effect. These works are cut from the same cloth, and stand as powerful symbols for the place of each individual in the universe. The message is abundantly clear; without a needle there would be no fabric, without each individual, no fabric of society.

-

As we follow the needle to its most abstract form, the significance of sewing as metaphor becomes abundantly clear. A needle is easily understood as an extension of the body, and nowhere is this more evident than in the two-screen video installation A Needle Woman, 1999 where the needle moves in a completely theoretical direction. In one projection Kimsooja stands motionless within various urban environments; in the other she lies immobile on a rock. The two projections create a compelling dialogue of opposites typical of her work in general. In the bustling city streets of Tokyo, Shanghai or Delhi, her role is non-changing; she stands alone, straight as a needle. She sews herself into the fabric of society, disappearing periodically just as a needle would. In the accompanying projection she lies upon a colossal rock in natural surroundings. In contrast to the fast paced city scenes, the only changing elements are the drifting clouds against a clear blue sky, and subtle nuances of light. Clearly, Kimsooja is a metaphor for the needle—she connects two parts and in the end disappears. Her role, or the role of her body, is to interact with the fabric of society and to direct our focus; then she disappears, just as a needle does after it’s job is done.

-

In A Needle Woman the body is understood as a needle within the fabric of life. Kimsooja elaborates on this important aspect; ”The mobility of my body comes to represent the immobility of it, locating it in different geographies and socio-cultural contexts. Immobility can only be revealed by mobility, and vice versa. Constant interaction between the mobility of people on the street and the immobility of my body in-situ are activated during the course of the performance depending on the context of the society, the people, nature of the city and that of the streets…I pose ontological questions by juxtaposing my body and outer world in ‘relational condition’ to space/body and time/consciousness.” [4] This captures the essence of Kimsooja’s overall approach, which ultimately relates to the idea of the singularity of the individual as part of an endless multiplicity. Looking at the world through Kimsooja’s eyes, we find ourselves looking at the universe through the eye of a needle. As Kimsooja ‘sews into life’ she simultaneously unravels the thread that is the entire conceptual basis for her work. Imbedded in the visible and invisible seams of her work we see how the traces of migration, war and cultural conflict necessarily affect ones identity and perception of reality—conveyed by an artist who is fully aware of the power of connective aesthetics. Her vision of the totality of art and life is beautifully conveyed through the symbolic power of the needle to mend, heal and connect. She uses a needle to guide us towards awareness and understanding in an approach to art that is intricately spun around the literal and conceptual practice of sewing.

[Note]

[1] Kimsooja consciously uses the term already-made instead of readymade.

[2] Suzi Gablik, The Reenchantment of Art, Thames and Hudson, NY, 1991. Page 130.

[3] From an interview with Olivia Sand that appeared in Asian Art Newspaper, 2002

[4] From an interview with Chiara Giovando, 2012 featured on Kimsooja's website. www.kimsooja.com

- — Essay of the Catalogue, 'Kimsooja - Unfolding ' from the artist's solo show at The Vancouver Art Gallery, USA, 2013.

A Homeless Woman- Delhi, 2000, 6:33 video loop, Silent.

A Homeless Woman- Delhi, 2000, 6:33 video loop, Silent.

Kimsooja and the Art of Place

2013

-

Place is important in the work of Kimsooja. The Bottari Truck in Exile (1999) was a work on the road, a truck heaped with bundles of clothing and bedcovers wrapped in brilliant silk fabric, travelling from one place to the next. In video work from 1999 to 2001, she traveled to many places around the world to produce pieces such as A Needle Woman (1999-2001) and A Laundry Woman (2000). More recently, she has devoted much effort to site-specific work that transforms an existing place such as the Crystal Palace in Madrid (2005) or the Teatro la Fenice in Venice (2006) through the graceful calibrations of light and color. In many ways, Kimsooja’s art may be described as a searching meditation on the nature of place—asking a number of questions such as what a place is, how it is defined, how long it lasts, who makes it, what the relation of place is to body, and how places are experienced. A Homeless Woman (2001) and A Beggar Woman (2001), videos that document her emplacement within teeming urban crowds as an anonymous female figure dressed in gray, whose silent, immovable presence is literally out of place, disrupting the traffic of befuddled pedestrians, if only for a moment. Some respond by pausing to inspect her, others are bemused by the camera that witnesses their presence. Still others fail to notice her at all, for whom she is nothing but the blurred place through which they hurry on their way to work.

-

The signals of critique, whether political or economic or geared to considerations of ethnicity or gender, are not hard to see. One could readily give Kimsooja’s art of place a reading that stresses an incisive reflection on the politics of identity, the social construction of gender and race, the economics of power and agency. Clearly, the crafting of place relies fundamentally on the coordinates of authority, social relations, and hierarchies keyed to ethnicity, race, and gender. And one need not look far in her discussions of her own work to find the artist’s corroboration of a political reading. She dedicated Bottari Truck in Exile, exhibited at the Venice Biennale in 1999, to refugees of the current war in Kosovo. Exile is an apt theme in regard to place because it means the loss of one’s native setting or milieu, one’s homeland. Kimsooja brought the truck loaded with bottari (Korean for “bundle”) from Korea to Venice for the Biennale. The work was not simply the truck, but the process of getting it from one place to another. She traversed countless national and international boundaries to transport bundles of laundry, the baggage in which exiles haul the traces of their existence. One thinks of transnationalism and the global flows of labor; of forced migrations; of international traffic in contraband; or of worldwide circuitry of capital pulsing through networks of markets.

-

The politics of power and powerlessness, of loss and theft are there, yet one senses that this framework does not exhaust what the work has to offer, where it wants to go. Kimsooja has spoken of the “dimension of pure humanity” as the special interest that drives her work[1]. She wants to ponder what she calls “the human condition and its reality” rather than indict political and economic systems. So she laments the refugees of the war in Kosovo rather than scrutinizing the conditions of the war’s existence. As an artist, human suffering concerns her in the first place, before the failure of social institutions and political will. An artist does not have to choose between the two, of course, but rather than critique and jeremiad, Kimsooja explores the intimate connection of art and moral sensibilities. She is a passionate observer of human beings. All of the work mentioned so far is evidence of an eye bent on the daily routines of human life, using them to register a wistful but wistfully beautiful sense of “the human condition and its reality.”

-

One might say that the common and principal function of religion, morality, and traditional philosophy is to posit a human condition as a way of explaining suffering and proposing a solution to it, or at least a way of enduring it. Kimsooja does not want her art to engage viewers as a religion or morality or philosophy. But it is clear that she wants her work to elicit profound aesthetic reflection. Everything she works with is something that bears the traces of human touch—the things women gather and clean, launder and stretch for the wind to dry. The clothing and bedding that touch us everyday, like a second skin. The things we bundle and carry from place to place, the things we save when the house is burning, when the village is destroyed, when the economy collapses. The things that are left when we are gone, that lie scattered on the ground, as in Sewing into Walking (1994) or in Portrait (1991), where a massive cloak of discarded fragments of cloth rises like a monumental gravestone, a mortuary icon of lives whose flesh is remembered in a dense clutter of castoff artifacts. It is the way of all flesh, this scatter of clothing. Sewing into Walking traces a walk through time as a patchy fabric of strewn memories, if even that. This is an elegiac work, bound to evoke in many viewers a sense of what the artist calls “the human condition.”

-

According to Buddhist teaching, everything, every feeling, is marked by impermanence, holding no place and passing away. Impermanence joins suffering and non-self as the three characteristics of existence, according to Buddhist thought. As one scholar has summarized the matter, “change, degeneration, and non-essentialism are fundamental features of everything.” [2] Nothing lasts, everything fails to satisfy, and there is no soul or self or substance that abides above it all. In short, there is no place to hold us that will not itself crumble into something else—except the dharma of release, or nirvana. Religions often describe a human condition because they want to diagnose the cause of suffering and to prescribe its solution—either through methods like the Four Noble Truths of Buddhism or the redemption that any number of salvific faiths offer their adherents.

-

But Kimsooja does not craft an art tasked with human salvation—either by divine means or by human politics. Her work is not preachy or propagandistic or doctrinaire because what really drives her art is the power of things to provoke thought, to arrest the mind and to fix it on something elusive and mysterious, something we want to take for a truth. Kimsooja wants to cultivate a mindfulness of what human beings encounter by virtue of being human. She ponders what is human—loss, yearning, beauty, routine, work—and does so in the sensuous terms of art that define the places of everyday life. Art is a heightened sensory consciousness, a poignant awareness of the world that opens up in the place that watching, touching, hearing, and making afford. “I’ve never practiced meditation in my life,” she once said in an interview, “but I found every moment for me was a meditation in itself. I reached a similar Zen Buddhism completely through my own way of meditation on life and art and its practice.” [3]

-

What does this make of art? The arts used to operate in the service of institutional religion, contributing to devotional life, decorating the altars of churches, shrines, pilgrimage sites, bodying forth the sacred in the daily exchanges between earthly mortals and heavenly powers in a sacred economy of pledge and favor, petition and reward. Popular imagery in everyday religious life still does that for believers today. But fine art has arisen over the last two centuries to occupy a different space in Western culture. For some people, art is a kind of therapy. It conducts a service of comfort, diversion, or uplifting pleasure. For others, however, the benefit must be described in terms of the meditative absorption to which Kimsooja alludes. Art is a way of refining or honing perception, for use as the means of introspection and as a social and cultural lens. In this approach, “aesthetic” does not mean beauty for the sake of beauty, but something more like sensuous cognition, a delicate tooling of the senses to scrutinize the world for the sake of a penetrating take on its weight and heat and chaos. And so we have Kimsooja’s artistic postulation of the human condition. This is neither religion nor politics; neither preaching nor moral reform. It is a limbic way of seeing, a projection of sensation into the larger world for the sake of feeling it vicariously in the skin of an artwork.

-

What does that mean? Kimsooja’s art is about the cultural work of looking. You may behold A Needle Woman in at least two ways. First, as a video projected on a screen in a gallery over the course of an exhibition for a few weeks. In this instance the video acts as a documentary, recording human actions at another place and time. The scene is a street, far away, a place that is not here, where you and I are standing. We look upon the place with curiosity. An image of the video’s installation in a gallery shows how this works: a bench invites you to sit down and watch an image projected from above. The image appears, as if through a rectangular aperture that has opened up in the gallery wall. In the dimly lit space, you are urged to sit or stand quietly and gaze upon the scene. You devote yourself to the task, if you have time, because you hope to see something interesting, something you’ve not seen before. You wait for something to happen. It’s art, after all. It’s supposed to do something. But when very little happens, the second way of seeing the piece begins to take shape. You glance furtively about the gallery at those standing near you. You glance at your watch, you wonder how long this will go on. Ineluctably, your perception shifts from looking at a video image-window in the wall to looking at people in your vicinity looking at a video image-window in the wall. You become aware of the discomforts of your body. If you’ve ever meditated, the feeling will be familiar. The scene moves from there, on the other side of the wall, to here, in and around you, and you realize that you are part of the art. The piece takes your time, your body, your patience and invests it in a work that includes you. You might look for the door. You might want to get out of here. Yet you’re intrigued by the two sets of looking—on the screen and in this room, and you wonder what you feel.

-

The boundaries of a work of art dissolved in the twentieth century. Art went from hanging on walls and perching on pedestals to happening in deserts and junkyards, on street corners and human bodies. With the dissolution of conventional boundaries came a redefinition of the place of art. So looking at A Needle Woman and A Laundry Woman, we ask: where is the artwork? Is it there, in the crowd’s response to or unawareness of the stolid presence around which they move? Or is it here, among us? Perhaps the two modalities are really one: we are yet another crowd in which the impassive worker woman stands. Perhaps our wandering eye is no different than the urban crowds in Tokyo, Cairo, Mexico City, London, or Delhi. Perhaps Kimsooja lures us into the gallery to sew the art world into the larger fabric of far-flung cities. To see her work is to be transported into a global work of art that shows us to ourselves. The boundaries demarcating the place of this art are disorienting, sublime. There is no getting out of it or away from it. Its center is everywhere, marked by the visual field that pivots on the gray figure of the artist standing steadfastly at the intersection of blinking gazes.

-

The steady feature of the artist in these videos is the structure that configures our visual field. Even when she is engulfed by the crowd that weaves obliviously about her, she remains our point of reference. Kimsooja transcends the world out there by holding her back irresolutely toward us, here. The camera is never forgotten. The people there are placed on a stage stretching before us. They were filmed for the purpose of being screened elsewhere. Place as local site is not singular, but part of a larger set of places that only the art viewer is allowed to see. The folks in Delhi don’t know or ever see the people in Mexico City or Shanghai—or us. We do, thanks to Kimsooja’s back. If she only wanted to be a needle, to transform her body into an inanimate object, it would not matter if we saw her from the side or front or any other angle. But we never see her face. This device structures the work of art by showing its proper side, where it is to be viewed—in a gallery. The place of art is a critical moment, a step back in space or time to see anew. Kimsooja wants art to be the world tweaked to make us conscious of place—our place, the place of others, and the place of art, arising in the interstices of culture. Place matters to her because she loves the beguiling way that art seizes our attention and invites our devoted scrutiny.

-

The appropriation of place for artistic purposes is something we see elsewhere in Kimsooja’s oeuvre. In the haunting beauty of An Album: Havana (2007), a ten-minute silent video created on site in Cuba. The camera runs for nearly three minutes down a pier overlooking the ocean and a cloudy horizon as lovers, tourists, and fishermen saunter along or sit on a stonewall. The video repeats for a second and third time, but each iteration increasingly blurs focus until in the final run the screen is a blank flicker that gradually transforms into bright light. In the second run we can still recognize the figures, but in the third sequence they evaporate in brownish haze. Deprived of sound and focus, the result is a lushly beautiful portrait of a place that steadily vanishes. What seems at first solid melts into the air, leaving viewers to wonder what their relation is to place that is no more. Memory of place may not be as sure as we’d like to think. With each replay, what we once stood before fades until finally it is gone. With nothing to see, it is not clear that the seer abides.

-

In an altogether different piece, Mandala: Zone of Zero (2003), the sound of Tibetan, Gregorian, and Islamic chant animates a scintillating object, a large target-shaped series of concentric circles composed of mirrors, fabric, and colored plastic. Circular mandalas are familiar to North Americans because of the “wheel of time” rituals conducted by lamas who created elaborate sand forms, often in museums [4]. Kimsooja’s Mandala resembles the Tibetan Wheel of Existence, a teaching tool used by itinerant Buddhist teachers who unfurled their charts to explicate the doctrines of Buddhism. The chrome ornaments that mark the four directions on the mandala even recall the jaws of the Lord of Death who holds the wheel in Tibetan tangkas. And like the wheel of dharma set in motion by the Buddha, and the samsaric cycle of rebirth and the circular arrangement of teachings illustrating the Wheel of Existence, Kimsooja’s wheel turns, too.

-

But the use of Buddhist, Christian, and Muslim chant in Mandala suggests that the artist has something broader in mind than the traditional Tibetan mandala. The object itself resembles a monumental roulette wheel more than a religious device—the star motifs recall the four-armed spindles at the center of roulette tables. Its glittering mirrors, sumptuous fabrics, gleaming chrome, and loud colors celebrate the ephemeral character of sensation, the flutter of fond feelings one associates with a jukebox full of favorite songs. All of this is very different from Buddhism’s diagnosis of the flitting mind’s need for the discipline of meditation to tame and control it. Yet although the art deco chrome ornamentation of the jukebox in Mandala reminds one of soda fountains and dance halls more than anything in a mediation hall, it does resemble popular Buddhist shrines and temples. One thinks of shiny golden statuettes of bodhisattvas, or of the long lines of brightly colored lanterns that appear each year at temples to celebrate Buddha’s birthday. Mandala spins and flashes like an incandescent turntable as the sound of chanting fills the room. Perhaps the mission of art, if it has one, is to reconnect introspection to the body and the senses. Whether you are in a disco or a Zen hall, you are in your body, and that is the means by which religion, mediation or art take place.

-

Both Havana and Mandala invoke Buddhist tradition in different ways. Mandala uses a familiar motif in Tibetan tangkas; Havana recalls the three features of all phenomena: impermanence, dissatisfaction, and no-self. Yet neither piece can be said to emulate Buddhism by offering itself as a tool for Buddhist practice. Both are about the power and place of art in modern life. Where Havana blurs, and finally erases a sense of place, Mandala seems to transpose the viewer from the body of the Buddha enthroned in the mental architecture of an imagined shrine to the splendor of the human body awash in sensation. The point is not therapy or religion or meditation technique, but a refinement of perception, the aesthetic cultivation of imaginative, felt life. Kimsooja’s work is not art in the place of religion, but art as sensory reflection on the places where life happens in the way it does.

[Note]

[1] Gerald Matt, "Interview" in Kimsooja. To Breathe/Respirare (Milan: Charta, 2005), 87.

[2] Brian Black, "Senses of Self and Not-Self in the Upanishads and Nikayas," in Irina Kuznetsova, Jonardon Ganeri, and Chakravarthi Ram-Prasad, eds., Hindu and Buddhist Ideas in Dialogue: Self and No-Self (Abingdon, England: Ashgate, 2012), 18.

[3] Matt, "Interview", 91.

[4] Pratapaditya Pal, Himalayas: An Aesthetic Adventure (Art Institute of Chicago in association with the University of California Press and Mapin Publishing, 2003), 256.

-

— Essay of the Catalogue, 'Kimsooja - Unfolding ' from the artist's solo show at The Vancouver Art Gallery, USA, 2013.

-

David Morgan is an art historian and Professor of Religion at Duke University. He has written on contemporary art, including such artists as Bill Viola, Magdalena Abakanowicz, and Ed Paschke. He is also author of several books on the history and theory of religious visual culture: Visual Piety (1997), Protestants & Pictures (1999), The Sacred Gaze (2005), The Lure of Images (2007), and The Embodied Eye (2012).

Mandala: Chant For Auschuwitz, 2000, Installation at Poznan Biennial in Hitler's former Office at Zamek, Poznan

Mandala: Chant For Auschuwitz, 2000, Installation at Poznan Biennial in Hitler's former Office at Zamek, Poznan

Essential Empathy

2013

-

Kimsooja gives herself to us. She does so through her art not simply because she is an artist, but because through art she can give to others. This exchange between artist and viewer has its rewards, offering access to the essence of human communication as well as essential connections to the larger reality of which we are a part. So following Kimsooja's path of communion among peoples and realms, empathy will be the focus of this essay.

-

When we look at Kimsooja's art and see her standing there, we experience her aliveness and partake of her vitality along with our own. Her art makes us feel our aliveness. When we see Kimsooja there, completely still, we also see beyond her and beyond ourselves. Along with her presence in the wind, with the sun and the moon, we sense something more. She endeavors not so much to represent so we can see, but to be one with the world through her work so we can recognize our being too.

-

In this way she participates in what cultures have always done. The names of those makers have not come down to us, so we praise past societies without individual recognition. But as she takes up her ancient charge we know her name or do we? To be her art, she consciously steps out of self, taking on a one-word name that "refuses gender identity, marital status, socio-political or cultural and geographical identity by not separating the family name and the first name.[1]"

-

Making art as one's way of being, or more accurately way of becoming, is to see art as a path. It can also be a reminder of our shared path, and in that way art is like religion and philosophy. But unlike these other fields of endeavor, art alone can be an experience that words on a page can never quite be. More than explaining a connection between the mundane and spiritual realms, between what is perceived by the senses and what is sensed by the mind, in art these can unite and be one. Making art with this aim of ultimate meaning is an act of hubris (punishable by the ancient Greeks), and a dicey claim in our world today. So this is a precarious start for an essay, though for the work of Kimsooja, a necessary one. Her ambition calls for no less.

-

Artists, like philosophers and theologians, are in the business of understanding the relation of the everyday to something greater: ideas, values, the ethereal. But it's not just a professional thing. It's what we do as humans and have done since the beginning of time. This is how we live and must. Each generation, each individual must find their meaning or live a life without it. Kimsooja's concerns are both with the here and now and beyond this place and time. Consciousness overtakes self-consciousness. How can we talk of this? "Spiritual" conjures notions too religious or new age-y for those in contemporary art, while the "unconscious" had a place earlier in the twentieth century, with the birth of psychology. The ambiguity of the ethereal, the other worldly, or unknown, means that it tends to be left out of discussion or to remain tacitly unspoken. "Universal" is a word banished by postmodernism. The claim to represent humanity is a totalizing concept that makes the use of this word suspicious; the complexity of social and cultural difference makes it taboo.

-

An understanding of Eastern philosophy, religions, and culture are ways to think about for Kimsooja's art; they clearly enter into the very nature of who she is. Some have expertly written of this, and these references remain central sources for knowing for her art, but there is more, not just because she is a person of our times who lives and works across cultures, but also because there has been a rich cross-pollination between Eastern and Western thought for centuries now. So, while Kimsooja's work is grounded in Asian philosophy[2], I have chosen to write about her work through the lens of the Western pragmatist philosophy of John Dewey, who was himself influenced by Taoist and Buddhist philosophy[3]. Turning to Dewey, we encounter the ideas of a humanist not embarrassed to venture into the wholeness of the enterprise that is life, because he, like Kimsooja, believed that a wide view is necessary and that art is the most meaningful way to achieve it.

-

As Dewey saw it, life compartmentalized into high and low, and values categorized as profane or spiritual, material or ideal, betrays the nature of things. Likewise, he felt that dividing occupations or interests into practice and insight, imagination from doing, significant purpose from work, and emotion from thought and doing, is to mistake human nature. But when they come together, are one, as in Kimsooja's work, we can experience "deep realizations of intrinsic meanings," " the sense of reality that is in them and behind them," as they tell "a common and enlarged story," and Dewey believed, the ideal can be embodied and realized[4]. Then distinctions of mind and body, soul and matter fade away.

-

To Dewey, this sense of continuity between the mundane world and something greater comes with experience, not just by living over time but by living life in a reflective, consciousness way[5]. For Kimsooja, her body is her medium and instrument conscious experience for others, not merely for expression or representation. And Dewey firmly believed, as Kimsooja demonstrates, that the senses, our own bodily capacity can be used directly to access the "spiritual, eternal and universal."[6] In Taoism, these realms are understood as one universal and ubiquitous vital energy. For Dewey we can know this through art.[7] The aliveness and vitality that art produces makes sense of life's experiences as it generates continuity between the earthly and eternal.

-

Thus, the experience of art (and for Dewey, art is an experience rather than an entity or object ) puts us in touch with the spiritual, non-physical world. But just as not all experience possesses insight or continuity, not all art rises to the level where it achieve a union of the material and the ideal. Yet when looking at Kimsooja's work, we understand Dewey when he says: "The depth of the responses stirred by works of art shows their continuity with the operations of this enduring experience" because such "works and the responses they evoke are continuous with the very processes of living." Her works affect what this philosopher called: "The mystic aspect of acute esthetic surrender, that renders it so akin as an experience to what religionists term ecstatic communion." [9]

-

Being consciously alive rises to the level of the aesthetic. It occurs, to Dewey, when we are fully and completely present in the experience of making and perceiving, but this does not only happen in the act of making art; it can happen in life.[10] For him, like Kimsooja, to live well, in an aesthetic or art way, is to be fully conscious, open, awake. As we are continually evolving in a state of becoming, we need to continually practice awareness. In Dewey's system of thought, in which each individual is responsible for themselves and for advancing society, practice involves putting one's values to work. His concept of the aware individual for his Pragmatist philosophy finds alignment with Buddhism's concept of buddha mind an awakened state of consciousness which respects both everyday action and the search to enlightenment as the same path. But whereas in Buddhism and Taoism this is achieved through meditation, Dewey advocated art. The work of art, in Dewey's view, as an object of practice can be a path to self-realization.

-

This path includes understanding others, and in experiencing art, we can experience others. On one level, in viewing art we can share the feelings of others, what we commonly call empathy. On another level, in art we can be with others, something we might describe as an experience of humanity. Dewey knew that empathy was the basis for any social enterprise. Art, for Dewey, had this great capacity for empathetic experience because, he believed, experiencing art is an act of re-creation:

-

Works of art are the means by which we enter, through imagination and the emotions they evoke, into other forms of relationship and participation than our own. We understand it in the degree in which we make it a part of our own attitudes, not just by collective information concerning the conditions under which it was produced. We accomplish this result when, to borrow a term from Bergson, we install ourselves in modes of apprehending nature that at first are strange to us. To some degree we become artists ourselves as we undertake this integration, and, by bringing it to pass, our own experience is reoriented. This insensible melting is far more efficacious than the change effected by reasoning, because it enters directly into attitude. [11]

-

How might this apply in the art of Kimsooja? A Homeless Woman - Cairo (2001) becomes an object of interest, even of compassion, on the part of passersby who pause to consider her manifestation of a human condition that till then had been almost invisible. In A Beggar Woman the artist presented herself to people in the streets of Delhi (2000), Mexico City (2000), Cairo (2001), and Lagos (2001). A different manifestation of this work occurred with Beggar Woman: Times Square (2005). Misinterpreted in the press as a gesture flying in the face if this city's truly needy, we might contemplate the questions, How do we draw attention to need? Can we experience others throughout a city, beyond just one city, holding in our hearts their hunger? Is acknowledgment of them acceptance without change? Who is in need? Who is present? Who offers what to whom?

-

Have you ever received a comment from a homeless person that stayed with you even though you gave nothing, while a thank you in return for money given on another occasion was not a memorable moment? Here the hands of Kimsooja's sitters are in a gesture simultaneously receiving and offering, being needy and charitable, troubled and wise. A practice in many religious traditions including Hinduism, Jainism, Buddhism, and Christianity, in which beneficence is manifested through both giving and receiving this act of engagement contains all things. [12]

-

Other empathetic works, beginning in 1995 with Sewing into Walking - Dedicated to the Victims of Gwangju, have taken the form of memorials. Clothes stood in for persons, spread out on a mountainside where tragedy had struck. It was a commemoration of as many at 2000 killed there as they rose up against the dictatorship of then-president Chun Doo-hwan. And it was a poultice for the earth. This incident, called 518 to signify its start date of May 18, found a parallel in 9/11 when later Kimsooja was moved to a enact a loving gesture of remembrance. In Epitaph (2002) she laid a single bedspread at Greenlawn cemetery in view of New York's skyline. Clothes, used as in Gwangju, were laid out on the floor of Hitler's former office in Poznan, Poland, to form Mandala: Chant for Auschwitz (2010), while cloth in all its colors and forms flow through four screens of Mumbai: A Laundry Field (2007-08), standing "for human presences and the questions that concern us all," [13] and creating a wider circle of life, not just of this place but many. On this occasion, as in other works, she also draws upon the ancient form of the mandala as a symbol of the universe and a vehicle of practice for focusing attention and bringing one in touch with a realm beyond the profane.

-

Carpets of clothes led to newly fashioned carpets with Planted Names (2002). Four woven works memorialize those who made the Middle Passage, packed in rows aboard ships, and then planted in rows the vast carpet of the former rice fields of the plantation site for which they were made [14]. In part inspired by the artist's experience the year before in Nigeria, this work was preceded by Bottari: Alfa Beach (2001) in which the sea sits atop the sky. This inversion is an empathetic response, she said, to "the saddest line I've ever seen in my life, thinking of the destiny of the slaves and their deprived freedom. Thus the flipped horizon was, for me, a disturbed horizon, a disoriented sense of gravity and of the slaves' psychological return I perceived in the curls of the waves reaching the same shore from which they had left." [15]

-

Kimsooja embraces the many associations of water: purification and cleansing, the depth of the womb and the vastness of the universe, its lunar cycles or the mind, and fluidity, as Taoism tells us, is the flow of energies and the inevitability of impermanence. In A Lighthouse Woman (2002), a companion to Planted Names, she created a witness to the waters' histories of pain through an oversized needle-like object surrounded by water. Its repeating, hour-long sequence of nine hues projected onto the lighthouse caused it to change as if breathing, saturating it and spilling into a pool the color. Viewers gave time to see this work, participated in being witnesses to time. And in experiencing A Lighthouse Woman they could experience empathy, not as an idea but, as Dewey said, through their individual senses they could actually experience "the spiritual, eternal and universal." Visited communally, there was communion.

-

The empathy of each of these works was made real through the use of historical and geographic reference and the artist's astute choice of tangible, material form, yet became the embodiment of others. In perceiving these works, as Dewey knew, we come to understand the wider story of humanity over time and to appreciate others' struggles. This happens across cultures, and even if we think we are more critical and aware of cultural differences than Dewey's generation, there's some truth as he says: "when the art of another culture enters into attitudes that determine our experience genuine continuity is effected. Our own experience does not thereby lose its individuality but it takes unto itself and weds elements that expand its significance"; then experience is one of "complete interpenetration of self and the world of objects and events," transforming into "participation and communication." [16]

-

In Kimsooja's work empathy of specific moments and situations gives way to a greater sense of oneness in humanity. This is the experience we have of Kimsooja's magnum opus, A Needle Woman. Begun in 1999, it is the embodiment of the fluidity of ourselves and our self into others, of time flowing into time, of place flowing into place, of oneness. She is the needle and yet the eye of the needle. She is the key that opens our vision, yet at the same moment the keyhole through which we pass. She shifts seamlessly, fluidly, between being solid and there, to empty, a shadow. Thus, in Needle Woman, we have two sides, too spectator and participant, as we looking at and moving into the scene, seeing others flowing along, being in the flow. Here our full participation is the transformation through the experience of art.

-

It has often been remarked that here the artist remains anonymous by not revealing her face. But it is more: she and all the persons in the frame are part of a larger, unframed whole: everything, everywhere. We understand this when this artist says, "I have an ambition as an artist: it is to consume myself to the limit where I will be extinguished. From that moment, I won't need to be an artist anymore, but just a self-sufficient being, or a nothingness that is free from desire." [17] Thus, Kimsooja aspires to a level beyond that of the experience of others and their story, and even beyond humanity as she seeks to approach the experience of a greater realm. To do this, art is a path not a goal, and a way to achieve full self-realization.

-

Taoism says the human mind before creation is pure emptiness, and that within this emptiness or void resides all potential. With awareness our mind can return to this state of emptiness, once again becoming part of it, connecting us to the universe and, during moments of insight, producing a sense of oneness with all things. This mental state is not a matter of representing reality; it is a state of being. This all-inclusive reality connects with our own mundane self because it is already ours or, better, it is already us. When Kimsooja speaks of "being consumed to the limit," she participates in that wholeness and is one with it. Art that evokes this multi-dimensional connection possesses an empathetic essentialism that goes beyond coming in touch with the emotions of others to achieve true identification, an understanding of being.

-

This level of empathy has been called by Gonzalo Obelleiro "imaginative empathy." It "is concerned with the essence of emotion, not the specifics of its manifestations," he writes, finding Dewey's philosophy of experience useful to ground a pedagogy imaginative empathy [18]. It is true that in addition to art's practical social roles of producing empathy, hence, creating an empathetic state of awareness, Dewey also felt that imagination through art played a social role [19]. But imagination in art and in common parlance has a sense of flights of fancy rather than of truth of experience, so here I prefer to recast this empathy found in the essence of emotion, as "essential empathy."

-

In A Needle Woman—Kitakysuhu (1999) the artist lies on an exposed rock of a mountain. Her stillness between earth and sky allows us to perceive the connected transitoriness of all nature, human as well as earthly and heavenly. Moving beyond self, she says: "Over time, I find that my body, with its duration of stillness—breathing in the rhythm of nature—becomes itself a part of nature as matter, neutral, a transcendent state. To me it is like offering and serving my body to nature. [20]" Likewise in Laundry woman—Yamuna River, India (2000), we experience, as she did, a similar oneness. Standing downriver from a cremation site, she faces the ephemeral joining the eternal. She des not represents or expresses this moment of passage but achieves it in a complete enlightened state of awakeness. And when this was achieved, she said, she "finally realized that it is the river that is changing all the time in front of this still body, but it is my body that will be changed and vanish very soon, while the river will remain there, moving slowly, as it is now. [21]" Our life is fluid, always changing, as we float in the river of the universe. As with A Needle Woman, she is in the picture yet evaporates from it, opening up the space for us to enter. As viewers, she gives us a glimpse of an awakened state: initially what it looks like, then with time, if we can achieve a deeper state of consciousness and presence, the chance to fuse and become one with her, replacing the artist, participating ourselves. So her art, like potent, sacred objects of cultures throughout time immemorial are not representations but means to this state of essential empathy, not the picture of it.

-

One of the primary aims of perceptual awareness for Dewey is for us to become conscious of the consequences of our actions, on other peoples and humankind, and for the planet. Today we think "planetary" in regard to ecological and environmental stewardship, but Dewey was also thinking in less tangible ways. With an understanding our individual effect on the greater whole, Dewey modeled a responsive and elastic web of consciousness in co-existent, recalling the Buddhist concept of interconnectedness as envisioned as Indra's Net: all things are a part; each reflects the whole; each affects and is affected by every other part.. With a belief that art was useful in guiding personal development toward social good, Dewey seized upon art's exceptional ability to create feelings of empathy and, thus, deeper understanding of the human condition and existential condition. For this he depended on art, for he knew it was essential to imagine a better future.

-

In other works, such as A Wind Woman (2003), Kimsooja becomes nature. In Earth—Water—Fire—Air (2010) she works at the site of a nuclear plant in Korea. For A Mirror Woman: The Sun & the Moon (2008), filmed on a beach in Goa, India, she created the moment of eclipse, when the sun and moon become one. The artist, it could be said, is gone in these works, but rather she is fully present with everything. Doris von Drathen has so aptly written of this work when she says the space the artist occupies is "the dividing wall of the mirror that generates consciousness," from which "she can view the impossible, open her range of vision into the cosmos, intensify her own sense of consciousness towards transcendence. At this moment of absolute presence, an ethical dimension reveals itself," whish is at once "the relinquishment of an identity that is defined by belonging" and "an awareness that concentrates utterly and absolutely on the Self." And here, too, we participate as: "The viewer merges into the incessant breathing of the sea, as it gives forth its waves, allowing them to rise and subside in eternal circuit...the viewer becomes susceptible to the circuit of the celestial bodies in the selfsame endlessness of their return [22]. Our full existence demands this connection to something larger.

-

Artists can be insightful and make insightful art. If we are perceptive, art can give glimpses of insight. But rarely is art insight. Yet this happens when Kimsooja embodies oneness or, Dewey's terms, continuity, giving herself to us and, when we experience it as we give ourselves to her art and fully participate in it. Participation. It's a word Dewey chose [23], but which has taken on a new meaning in art today as we have lost the capability to participate with art objects, and talk about engaging viewers in modes of participation such as collaborative authorship or other forms of making. Spectatorship connotes detachment, looking at the surface of things or actions. In American and European contemporary life the spectacle society is one of superficial and mediated relationships [24]. The spectator does not feel empathy, but the participant does. And only as a participant can we partake on yet another level of the essential empathy that Kimsooja experiences and which become her art.

-

To be a participant in Kimsooja's art does not require sitting in Times Square or being with the artist on a beach in India. It can happen in front of a video in a gallery. To an exceptional degree her art revives the experience of art Dewey knew—where being with art makes all the difference. If we think about the viewer as involved in empathetic relation to the artist's experience, to others' experiences, and to the essence of empathy, then as participants we are caring, hence engaged. Caring, the engaged audience functions like the artist, invested in the moment [25]. This parallel of artist-to-audience is so fundamental that as we experience art we "become artists ourselves." [26] Kimsooja gives us the possibility to do this with her art. If we fully participate, the experience is ours.

[Note]

[1] http://www.kimsooja.com/action1.html

[2] See Interview with Kimsooja in Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, Eds. Jacquelynn Baas and Mary Jane Jacob (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 212-219.

[3] In dealing with a wider realm, Dewey advocated a philosophy that "accepts life and experience in all its uncertainty, mystery, doubt, and half-knowledge and turns that experience upon itself to deepen and intensify its own qualities—to imagination and art." John Dewey, Art as Experience (1934; New York: Penguin, 2005), 35. For a discussion of Dewey's personal connections to Eastern philosophy, see the author's essay "Like-Minded: Jane Addams, John Dewey, and Laszlo Moholy-Nagy," in Chicago Makes Modern: How Creative Minds Changed Society, Eds. Mary Jane Jacob and Jacquelynn Baas (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2012), 23-25.

[4] Ibid., 21, 28

[5] Dewey wrote: "The existence of art is the concrete proof…that man uses the materials and energies of nature with intent to expand his own life….Art is the living and concrete proof that man is capable of restoring consciously, and thus on the plane of meaning, the union of sense, need, impulse and action characteristic of the live creature. The intervention of consciousness adds regulation, power of selection, and redisposition. Thus it varies the arts in ways without end. But its intervention also leads in time to the idea of art as a conscious idea—the greatest intellectual achievement in the history of humanity." Ibid., 26.

[6] Ibid., 32.

[7] Dewey wrote: "The conception of man as the being that uses art became at once the ground of the distinction of man from the rest of nature and of the bond that ties him to nature…art itself is the best proof of the existence of a realized and therefore realizable, union of material and ideal...There is no limit to the capacity of immediate sensuous experience to absorb into itself meanings and values that in and of themselves—that is in the abstract—would be designated 'ideal' and 'spiritual.'" Ibid., 26, 29, 28.

[8] Ibid., 344.

[9] Ibid., 28-29

[10] We might think here of when someone remarks they are "living the project," being so fully engaged. We see it in the excitement or focus someone give sot what they are doing, their skillful command but with the presence of the moment that is each time lived anew. This Dewey called esthetic. By way of example, he wrote: "An angler may eat his catch without thereby losing the esthetic satisfaction he experienced in casting and playing. It is the degree of living in the experience of making and of perceiving that makes the difference between what is fine or esthetic in art and what is not. Whether the thing made is out to use…is, intrinsically, speaking, a matter of indifference….Whenever conditions are such as to prevent the act of production from being an experience in which the whole creature is alive and in which he possesses his living through enjoyment, the product will lack something of being esthetic. No matter how useful it is for special and limited ends, it will not be useful in the ultimate degree—that of contributing directly and liberally to an expanding and enriched life." Ibid., 27.

[11] Dewey, Ibid., 347 - 348. This proceeds from Dewey's premise that: "Without an act of recreation the object is not perceived as a work of art." Ibid., 56

[12] See also http://www.dharmasculpture.com/buddha-varada-mudra-sanskrit-boon-granting-charity-hand-gesture.html

[13] Rosa Martinez, "A Disappearing Woman," in Kimsooja: To Breathe (Seoul: Kukje Gallery, 2012), 22.

[14] Planted Names was made for and exhibited at Drayton Hall, Charleston, South Carolina, commissioned by the author for the Spoleto Festival USA in 2002. Interestingly one of the descendents of this plantation family, Bill Drayton is the founder of the progressive social entrepreneurship organization Ashoka that uses empathy-based ethics as a keystone to working together to make change.

[15] Martinez, 21.

[16] Dewey, 349, 22-23

[17] Ingrid Commandeur, "Kimsooja: Black Holes, Meditative Vanishings and Nature as a Mirror of the Universe," in Kimsooja: To Breathe, 9.

[18] See Gonzalo Obelleiro, “Imaginative Empathy in Daisaku Ikeda’s Philosophy of Soka Education,” conference paper for Soka Education: Leadership for Sustainable Development, Soka University of America, February 11-12, 2006, 39-51. www.sokaeducation.org/images/4/48/Imaginative_Empathy-Obelleiro.pdf. Obelleiro argued that empathy, in line with Buddhist tradition, is not the mere act of re-experiencing one’s own sufferings, but when “[w]e feel empathy when we partake on the essence of the emotions that person is experiencing.” To the author, this is supported by Dewey’s philosophy of experience because it “shares with Buddhism the basic epistemological premise of the oneness of self and environment and oneness of mind and body,” and because “in its clear humanistic approach, it privileges human interactions and regards ethics as not as fixated in a particular framework of rules and maxims, but as the art of creative, inner dialogue between primary experience and critical reflection.” To Obelleiro, “Dewey makes it clear that concepts like imaginative empathy are not simply theoretical concepts but are modes of praxis or manifestations of philosophy as art, which can only be learned in experience, particularly in interaction with other human beings.” So he concludes: “it is only through the creative integration of the two, direct experience and cultivation of mind and spirit, that imaginative empathy can be attained. The kind of artistic skill required for this integration can only be learned from another human being, for it is the quintessential human quality. Some call it wisdom.”

[19] Dewey wrote: “The first stirrings of dissatisfaction and the first intimations of a better future are always found in works of art.” Ibid., 360.

[20] Kimsooja, Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art, 217.

[21] Ibid., 217.

[22] Doris von Drathen, "Standing at the Zero Point," in A Mirror Woman: The Sun & The Moon (Tokyo, Shiseido Gallery, 2008).

[23] As stated previously, Dewey said, experience “when carried to the full, is a transformation of interaction into participation and communication”; and also: “Works of art are means by which we enter, through imagination and the emotions they evoke, into other forms of relationship and participation than our own.”

[24] Here, of course, I am referring to Guy Debord’s The Society of the Spectacle, (New York: Zone Books, 1994, originally published in French 1967).

[25] Robert M. Pirsig, in his classic Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, distinguishes between being involved and being a spectator. Care, for Pirsig, is what makes one’s work or actions an art. See Robert M. Pirsig Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance (New York: Harper and Collins, 1974), 34-35.

[26] Dewey, Art As Experience, 348

- — Essay of the Catalogue, 'Kimsooja - Unfolding ' from the artist's solo show at The Vancouver Art Gallery, USA, 2013.

A Needle Woman, 2005, Sana'a (Yemen), one of six channel video projection, 10:40 loop, silent

A Needle Woman, 2005, Sana'a (Yemen), one of six channel video projection, 10:40 loop, silent

Gnomon of Place, Gnomon of Foreignness

2013

-

"Hospitality is certainly, necessarily, a right, a duty, an obligation, the greeting of the foreign other as a friend but on the condition that the host, the Wirt, the one who receives, lodges or gives asylum remains the patron, the master of the household, on the condition that he maintains his own authority in his own home, that he looks after himself and sees to and considers all that concerns him and thereby affirms the law of hospitality as the law of the household, oikonomia, the law of his household, the law of a place…." —Jacques Derrida, "Hostipitality" [1]

-

The six videos projected simultaneously that comprise the Korean artist Kimsooja's A Needle Woman (2005) present the artist wearing precisely the same clothes, standing precisely the same way, and, it would seem, at the same time of day, the sun shining down. She is absolutely still amid passing crowds of inhabitants in Patan, Nepal; Havana, Cuba; N'Djamena, Chad; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil; Sana'a, Yemen; and Jerusalem, Israel. The crowds react differently to this odd figure, clearly a foreigner. They are presented in slow motion, with no sound, which only emphasizes the sense of movement, instant reaction, passage.

-