2003

Nicolas Bouriaud │ Interview

2003

Flaminia Generi Santori │ Interview

2003

Mary Jane Jacob │ 'In the Space of Art: Buddha and the Culture of Now' Interview

A Needle Woman - Kitakyushu, 1999. Single Channel video. 6:33 loop, Silent

A Needle Woman - Kitakyushu, 1999. Single Channel video. 6:33 loop, Silent

Interview

2003

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

In Buddhist philosophy, there is a notion which has a great importance: the impermanence of the world we live in. The needle woman stands in front of passing-by elements, like as if you were stressing on this impermanence, or on the fluidity of things. How does the Eastern way of thinking match contemporary art history, in you work? -

Kimsooja

The impermanence of our lives is an important notion in my work and thinking and with this perception, comes a deeper compassion for human beings. Meditation about impermanence has been shading in my work since I first started the sewing pieces in the early 80's — connecting fragments of my deceased grandmother's clothes. -

Buddhist philosophy, especially Zen Buddhism is similar to the way I perceive and function in the world. However, the ideas in my work are created from my own questions and experiences, not from Buddhist theory itself. (It is more complicated — as I was brought up formally a catholic, and practiced also Christian for some time, but Korean daily life practice is greatly dominated by Confucianism, mixture of Buddhism, and Shamanism.)

-

Certainly, where my immediate perceptions and decisions in art making meets the disciplines of Buddhism — making art and living my life are not consciously borrowed from theories. I intentionally stopped reading over a decade ago to concentrate and follow my own thoughts, but I recently started reading again especially on Buddhism as I find amazing similarities in my work and perception of life in it.

-

I might add that, the Eastern way of thinking inhabits every context of contemporary art history not just as a theory but as attitude melded in ones personality and existence and is inseparable with Western thinking.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

Do you think that oriental (eastern) thought has a real impact on the contemporary art world, or is it only a postmodern kind of exoticism, a decor for western aesthetic investigations? -

Kimsooja

It would be unfortunate if the Western art world considered Eastern thought as a decor for Western aesthetic investigation — as if it were another element to add without noticing the fact that it is a way — in the process of making art. It is always there — as a dialectic — in all basic phenomena of art and life together. Eastern thought often functions in a passive and reserved way of expression, usually invisible, non verbal, indirect, disguised, and immaterial. Western thought functions more with identity, controversy, gravity, construction in general rather than de-construction, and material than immaterial compared to Eastern. The process finally becomes the awareness and necessity of the presence of both in contemporary Art. It is the 'Yin' and 'Yang' — a co-existence that endlessly transforms and enriches. -

Nicolas Bouriaud

You could have chosen to ignore your Korean cultural background, but you decided to use it as a material. In a way, especially the Bottari series, your work Post-produces formal elements from this already existing Korean shapes and patterns. But formally speaking, your exhibitions are playing with minimal art. Would minimalism play a special role onto this connection between East and West? And which movements or artists were the most influential for you? -

Kimsooja

I have always used my personal life as the basic material for my work — hoping it would embrace the other. If I hadn't grown up and lived as a married woman in a Korean society, I wouldn't have chosen these traditional bedcovers. In Korea, they have a special meaning as the bed is the site of birth and death — of sleeping, loving, suffering, dreaming dying — it frames our existence. The bedcover is given to and used by newly married couples in Korea with messages beautifully embroidered and emblematic of wishes for love, fortune, happiness, many sons, and a long life.... it is so easy to notice it's contradiction when we see these symbols. I can't interpret my own culture with other culture's materials in the same way..... I try to find materials in their own context, but it always ended up with me bringing materials from Korea as theirs looked so neutral and hard to get the sense of the energy I feel from ours. -

As for minimalism, I agree with you as a part of the nature of my practice but in the sense of extension of it's interpretation to the life as well as formalistic terms. The Japanese art critic Keiji Nakamura perceives my work as 'existential minimalism,' and this makes sense to me also. I greatly respect minimalism in the sense of the process of making art as well as it's vision. However the contents minimalists deal with are often maximal. It's hard to name any particular artist who was influential to me as I've been influenced in a way from anyone whom I have an opinion on their work-even from the ones we don't agree with. Yet, there is one statement by John Cage I saw it written in the bottom corners of an empty container at the 1985 Paris Biennale; that has reverberated for a long time in my mind. "Whether we try to make it or not, the sound is heard.".

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

You are partly working with objects and surfaces made by other people. Of course the readymade is not a stake anymore, but in your case it could be questioned on a social or psychological level. The notion of existential minimalism could bring us to this direction, too, because it carries the idea of humanity, concrete people making products in a particular context. So what is the status of those objects in your mind and in your work in general? Is it a neutral process to use those bedcovers, or do you consider their context of production and the condition of the workers? And, more generally, what is the status of pre-existing things in an artwork? -

Kimsooja

Analyzing the nature of my already-mades, can give a significant clue to the context of my work. I've been using objects from Korean domestic daily life significantly in my series, 'Deductive Object' from the early 90's. Here, I chose traditional Korean domestic already-mades; wooden window frames, reels, drums, and agricultural tools; a saw, shovels, forks, hooks... and wrapped them with old Korean clothes and bedcovers. -

Now, I as am working exclusively in New York, I'm using objects found here; a child's toilet, a swing, vessels and an old directory board from a department store...etc. I've been thinking more about people who owned and used the objects and their traces rather than the people who made or manufactured them in those objects and I'm noticing that they are symbolically genderized in form and function.

-

Perhaps we need to re-define the notion of readymade in a larger context than relying on Marcel Duchamp's investigation — especially in this mass producing, global networking era which needs constant re-definition. My work is about pre-existing things buried into our daily lives — not mentioned nor conceptualized in art history.

-

My work also includes a presentation of the daily life of women's labor and her domestic performance trying to re-define the social, cultural and esthetic meaning of it to create it's own context in contemporary art history.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

This concept of pre-existence of things is very interesting. In a way, one could say that you are working with the ghosts of the objects, their aura, trying to turn the invisible into a shared experience. The anonymous is supposed to be invisible; so is the past, mostly. Is that important for you to make them visible? -

Kimsooja

Yes. Depending on the nature of the already-made objects, my interest lies on different issues; for example, when I work with bed covers, I am working with pre-existing objects focusing more on the fact of 'pre-used' rather than 'pre-made' as I am more focused on anonymity of the bodies and the destinies of the couples rather than on anonymity who made the bed covers, although I am concern about the people who made them. -

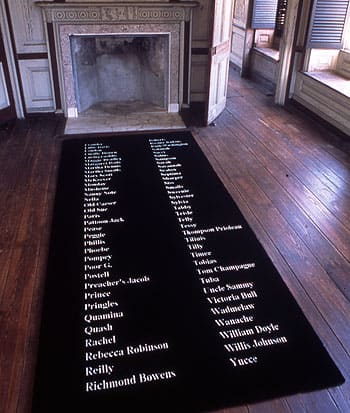

On the other hand, the folklore objects I've used, my interest lies more on the genderized nature and esthetic structure of the object and it's function in daily life rather than the anonymous beings who made or used them. But when I made a series of carpets which embeded names of the African American slaves who used to work for the plantation houses in the US, I was trying to combine the nature of the painstaking labor of carpet weavers and that of the African American plantation slaves emphasizing both of theirs hardships as I find carpet weaving and plantation job is similar jobs in different dimension. I wish to reveal this anonymity — as myself — one of the anonymous.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

The Needle woman is a central figure in your video works: You are standing in front of people and objects, right in the middle of a maelstrom of things, as if you were out of the world. Is that another figure of anonymity (the voyeur? Or are you even more into the world by watching it pass?) -

Kimsooja

It is the point of the needle which penetrates the fabric, and we can connect two different parts of the fabrics with threads, through the eye of the needle. -

A needle is an extension of the body, and a thread is an extension of mind. The traces of mind stays always in the fabric, but the needle leaves the site when it's medialization is complete. The needle is a medium, a mystery, a reality, a hermaphrodite, a barometer, a moment, and a Zen.

-

Nicolas Bouriaud

Watching the needle woman, I was also thinking about a negative image of the baudelairian flaneur, an archetypal figure of the occidental modernity. Are you inscribing your work in the field of modernity, or is it a notion that is totally irrelevant for you? -

Kimsooja

It is interesting to see my work discussed in this way — being compared to others from a completely different culture and social identity and also born at different time and space. My work is focused on the totality of life and art. One can see different realities in one persona or in art. Perhaps that is why one sees diverse similarities in my work. -

Nicolas Bouriaud

In a way, you are trying to capture the totality of human experience, which is quite rare. As you said, your work is not about any particular issue? Can you tell me what this ambition implies, and means? -

Kimsooja

Totality is the truth and the reality of things. And it takes time to clarify in language as a whole. I am interested in approaching the reality that embraces everything because it is the only way to get to the point without manipulations. Most people approach reality from analysis or 'from language to colligation' which is the truth', but I am proposing a 'colligation to be analyzed' by audiences. My working process is intuitive and I believe it's own logic. If I have an ambition, it is to be just a 'being' who has no need to be anyone special, but is freed from human follies and desires — without doing anything particular. 'Being nothing/nothingness' and 'making nothing/nothingness' is my goal. It is a long process. -

Nicolas Bouriaud

To be "freed from desires" sounds very buddhistic. Is the artist a kind of boddhisattva, who tries to free himself/herself and to liberate the viewer? -

Kimsooja

I remember the way desire was talked about in the 80's through the work of "simulationnist" artists such as Jeff Koons or Haim Steinbach : art was the absolute object of desire, a "pure merchandise," a perfect exchange value. Desire was examined in terms of compulsion and acquisition. So today, what would be the relationships between art and desire? -

In any case, artists have been constantly dealing with their own desire and audience. For me, artists' practices are similar to that of Buddhist monks' in the sense that they both try to liberate and to become beyond themselves. In this era of globalization and technology however, the self, the body, the spirit, and the other can be perused in many ways -Artists deal with different types of desires depending on their social and cultural context. Desire can be visualized in a physical object form which satisfies sense of 'possession' or in a psychological and metaphorical way that deals desire as another 'subject'. When Claud Viallat said 'Desire leads', I think he referred to another origin of art instinct which links and visualizes these two different source of desires. Artists cannot help ask what is the origin of their desire, and what role desire plays in their work. To understand that this is 'the subject' an artist confronts in the end, and to extinguish it.

─2003 Solo Exhibition Catalogue, 5 Continents Editions, pp. 45-57.

- Nicolas Bourriaud is a contemporary art critic and the director of Documents sur l'art, a bilingual magazine devoted to contemporary culture.

Interview

2003

-

Flaminia Generi Santori

In your work you have been using very consistently two media: fabrics and video. The most immediate connection one makes comes out from the title of one of your video works: the series Needle woman. Who is the needle woman? Is she a metaphor? Does she represents a condition of humanity, as the title of your show in Lyon would suggest? And what is the relationship between the needle woman and the fabrics use have been using? -

Kimsooja

The fabrics I've been using for my sewn work, Object, and installation were used Korean traditional costumes, bedcovers and used clothes which I found from anonymous people. These fabrics represent presence of body whose smell, memory and time is still there. On the other hand, a series of my video pieces represent and wrap the actual human body in immaterial way, while the fabric installations are materialistic way of representing and wrapping human body — yet it represents the invisible body. -

In my recent video performance A Needle Woman (1999-2001), my body stands as a medium between the viewers of the video and the people in the street where my performance is taking place, as if it functions as a barometer while weaving/woven (by) different nation, races, culture, society and economy by standing still in the middle of the busy streets in 8 different metropolitans in the world.

-

Apart from A Needle Woman video, I've been also examining the conditions of human being by putting myself in one of the lowest state of human being as A Homeless Woman, A Beggar Woman, A Laundry Woman and as a refugee by making Bottari installations — refugee as a persona, as a woman, and as a collective group of people in a broad sense of refugee in existential, social, cultural, and political context.

-

Flaminia Generi Santori

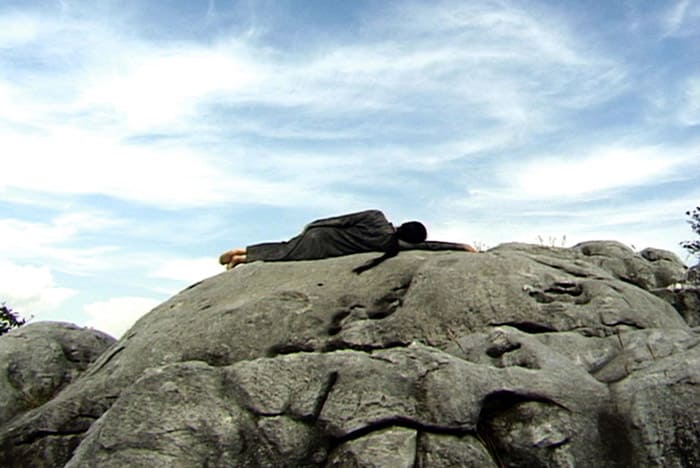

The needle woman might take different positions, like in Needle Woman - Kitayashu, in which she lies on a rock facing the sky perfectly still. Or she might take different names, like in Laundry Woman, where, in the same position, she faces the Yamuna river in Delhi... -

Kimsooja

As I mentioned earlier, the Needle Woman signifies a medium which connects different parts of the fabrics of society, culture and landscape — in that sense, A Needle Woman - Kitakyshu divides and links four different element of the world which are the earth and the sky, the human side and that of the nature. As long as my body functions as a mediator, A Laundry Woman is not different from the other performances although the position is different depending on the structure of the landscape and cityscapes. But I could say my work has also a parallel relationship to the structure of the painting in formalistic reading. -

Flaminia Generi Santori

In these works you stand perfectly still, in crowded cities in different parts of the world, or in the landscape. Watching them one cannot but think about how you managed to reach such an immobility and concentration. And also they made me think about the goal of so many meditation practices: the ability to live the present moment to its ultimate intensity, or the notion of impermanence. However you said that zen theory has not been important in your work... -

Kimsooja

Immobility comes out of mobility. I could reach to the immobility only by practicing mobility in my life. I was always thinking every moment is a meditation and the moment when a perception and an artistic decision comes up to my mind was Zen, but I'd never practiced Zen meditation. -

Flaminia Generi Santori

In all of your video installations the viewer is faced with your back, so that he shares your point of view. In Needle Woman the viewer is immersed in a 8 channels installation in which he witnesses you standing still in the middle of the most crowded streets of the world. Do you imagine the viewers standing on your back when you do your video performances? What kind of visual and emotional experience you project on your viewers? -

Kimsooja

It would have been very interesting if someone on the street stood right behind me posing exactly the same way I do. I would say the person who is standing behind me is the camera which is eyes of myself. This idea can be compared to my video I made in a crowed street in Istanbul in 1997 which takes people coming and going in Istiklal street by setting a fixed frame for an hour wrapping people into the camera lens which can be juxtaposed to my body. -

Flaminia Generi Santori

Time, it seems to me, is a crucial element in your work. Not only because of the duration of the videos but also because in all of them you watch transient elements: people in the streets, clouds in the sky or flowers in the river. Time and past experiences seem to be crucial also in your work with fabrics in which you use tissues which have been used already and carry with them the sign of past experiences. -

Kimsooja

The idea of impermanency of existences gives me a deep compassion for human being and has been embedded in my work since the beginning of my sewing practice till now — the fabrics I first sewn together were the remained fragments from my grandmother's clothes when she passed away — memorizing her presence. I've been living such mobile life from my childhood wrapping and unwrapping household and luggage and the strong memory I have from my childhood were the huge mountain in front which I was looking in the dark from our house yard and the passing by landscapes I used to see on our way to somewhere else from a bus or a train. Leaving people behind us from where I live and meeting new people in a strange city was part of my family life. -

Flaminia Generi Santori

You have been using the fabrics in a variety of contexts and often in public places, like in a old post office in Trieste (am I right?) and in the open air cafè in Central Park New York. You also took them, as Bottari, to different parts of the world in a work eventually dedicated to the Kosovo refugees. What is the relation, if there is, between private memory and public place, function and aesthetics? -

Kimsooja

Presenting private materials in public spaces sometimes provokes intimate questions such as table cloths and laundry installation I made with newly married couple's bedcover cloth from Korea. Eating in the bed, or Wrapping bundle/Bottari ( especially when it's refered to a woman) are Taboo in Korea. I am questioning this site of birth, sleep, love, suffer, and death considering as our frame of life and its reality in sexuality, morality, conflicts in humanity as well as its impermanency. On the contrary, the color and embroideries of those fabrics are brilliant and beautiful, while showing contradiction in reality of life which is not always same as these symbols signify and the esthetic structures I present in situ. -

Flaminia Generi Santori

Lately you have been working with lights and sound, like in Charleston or like in a lighted mandala you showed in Lyon. Is this a new direction in your work? -

Kimsooja

A permanent question and desire I have has a lot to do with possession and its void in Yin and Yang relationship in our world. The whole process of my work has to do with process of void in life and art and its extinguishment at the end.

-

— From the interview in 'Il Manifesto', Rome, 2003.

-

Flaminia Gennari Santori is research coordinator at the Fondazione Adriano Olivetti in Rome and adjunct professor of Italian Art History at New Hampshire University Italian Program. She holds a PhD from the European University Institute, in Fiesole and she was a Fullbright Scholar at the University of Chicago. She published 'The Melancholy of Masterpieces'. Old Master Paintings in America 1900-1914, Milan, 5continents editions 2003 and articles in Italian and British journals and books. With Annie Claustres and Anne Pontegnie she coordinates the research "Une Nouvelle Scène de l'Art", to be published by Les Presses du Réel in 2005. She contributes book and exhibitions reviews to the Italian daily newspaper il Manifesto.

A Lighthouse Woman, Spoleto Festival USA 2002, lighting sequence, Morris Island, Charleston. Photo by Rian King.

A Lighthouse Woman, Spoleto Festival USA 2002, lighting sequence, Morris Island, Charleston. Photo by Rian King.

Planted Names, Spoleto Festival USA 2002, A carpet with names of the African-American slaves from Drayton Hall plantation house, Charleston.

Planted Names, Spoleto Festival USA 2002, A carpet with names of the African-American slaves from Drayton Hall plantation house, Charleston.

'In the Space of Art: Buddha and the Culture of Now'

Interview

Jacob, Mary Jane (Independent Curator)

2003

-

Mary Jane Jacob

Let's talk about how sewing has been a contemplative practice for you and a way of connecting your body to a greater whole? -

Kimsooja

One day in 1983, I was sewing a bedcover with my mother and then at the very moment when I passed the needle through the fabric's surface, I had a sensation like an electric shock, the energy of my body channeled through the needle, seeming to connect to the energy of the world. From that moment, I understood the power of sewing: the relationship of needle to fabric is like my body to the universe, and the fundamental relationship of things and structure were in it. From this experience, for about ten years, I worked with cloth and clothes, sewing and wrapping them, processes shared with contemplation and healing. By 1992, I started making bundles or bottari in Korean — I always used old clothes and traditional Korean bedcovers — that retain the smells of other's lives, memories, and histories, though their bodies are no longer there — embracing and protecting people, celebrating their lives and creating a network of existences. -

Mary Jane Jacob

Korea was not a very visible part of the contemporary art world. You yourself came to the U.S. in 1992 on a residency at P.S. 1 in New York. Then Korea joined the ranks of international biennale presenters in the southwestern city of Kwangju, a place where Korean and American identity is sadly linked. -

[In May 1980 students and other demonstrators against martial law were killed by government forces with brutal force, the death toll mounting to 2000, though officials claim only 191. The U.S. was implicated in support of President Chun who seized power in a military junta and a wave of botched diplomatic that followed.]

-

Kimsooja

This is the site of a national tragedy. It is marked by anniversary reenactments each year. With my work for the first biennale there, Sewing into Walking: Dedicated to the Victims of Kwangju, I placed 2.5 tons of clothes in bundles on a mountainside at the Biennale site. It was the image of the sacrificed bodies. People could walk on them, listening to the "Imagine" song by John Lennon which, through the audiences' bodies, evoked the confrontation of stepping on bodies and guilty conscience, as well as memorializing the victims' lives. Over the two months of the show, the seasons changed and the clothes became mixed with the soil, rain, and fallen leaves, becoming like dead bodies: this was the installation scene I wished to create for the viewers. The audience — the Korean people — opened the bundles and removed nearly one ton of clothes; they hung some onto the trees and took others away with them. -

Mary Jane Jacob

Have your works, as a means of healing and connecting, been autobiographical? -

Kimsooja

When I went back to Korea in 1993, after spending time in the U.S. and having a different perspective on my own culture and gender roles in Korean life, I re-confronted the society as a woman and a woman artist. I started realizing my own personal history in bottari projects, using them more as real bottari than for an aesthetic context. My first video performance piece, Sewing into Walking-kyung ju (1994), resulted from an installation; in its documentation I recognized that my own body was a sewing tool, a needle that invisibly wraps, weaves, and sews different fabrics and people together in nature. For my next video performance, Cities on the Move — 2727 Kilometers Bottari Truck in 1997, I made an eleven-day journey throughout Korea atop a truck loaded with bottaris, visiting cities and villages where I used to live and have memories. Because the bottari truck is constantly moving around and through this geography, viewers question the location of my body: my body — which is just another bottari on the move — is in the present, is tracing the past and, at the same time, is heading for the future, non-stop movement by sitting still on the truck. And though I used myself in this work, I tried to locate a more universal point where time and space coincide. -

I realize now that Cities on the Move — 2727 Kilometers Bottari Truck emerged from the history of my family that moved from one place to another almost every two years, mostly near the DMZ area, because of my father's job in the military. We were wrapping and unwrapping bundles all the time; we were endlessly in a new environment, leaving people whom we loved behind and meeting new neighbors, as we passed from one city to another, one village to another. We were, in fact, nomads, and I am continuing the nomadic life as an artist, a condition which has become one of the main issues in contemporary art and society. Yet I am also aware that migration is just an extension of nature and we are literally in a state of migration at every moment.

-

Mary Jane Jacob

It seems like sites — out in the world — have become your studio for making art? -

Kimsooja

Usually, I don't like to make or create anything in nature because I am really afraid of damaging it. Instead, I decided to use existing elements which can be related to my idea of location/dislocation and its gravity and energy towards the future. In 1997 I did another work in the series, Sewing into Walking-Istiklal Cadessi, a video shoot in Istanbul. I experimented with documenting peoples' coming and going through the fixed frame of the lens; it was an invisible way of sewing and wrapping people. Then, with A Needle Woman project (1999-2001), I inserted myself in the middle of the busy street and looked towards the people of eight different metropolises in the world: Tokyo, Shanghai, Berlin, New York, Mexico City, Cairo, Lagos, and London. I considered my body to be a needle that weaves different people, societies, and cultures together by just standing still. Inverting the notion of performing and remaining fixed within the crowd, my body functioned like a barometer, showing more by doing nothing. The needle is an evident yet ambiguous tool, androgynous, maintaining contradiction within it. The needle functions only as a medium; it never remains at the site and disappears at the end. It just leaves traces, connecting or healing things. -

Each performance lasted 25-30 minutes, during which I just stared straight ahead. I eventually cut each tape to an unedited section 6-minutes and 30-second in length. In the beginning I had a difficulty resisting all the energies from people coming at me. By the middle of the performance I was centered and focused, and could become liberated from them. In the beginning my body was very, very intense, but in the end I was just smiling, liberated from all attention. I could see the light coming from the back, far from the front, over these waves of people. I was in complete enlightenment.

-

I didn't know where the smile came from but I was just smiling. Maybe it was the moment when I was freed from my self-consciousness and engaged with the whole picture of the world and people as oneness and totality beyond this stream or ocean of people in the street. I think enlightenment can be gained by seeing reality as it is, as a whole which is a harmonious state within contradiction that requires no more intentional adjustment or healing.

-

Mary Jane Jacob

Your personal posture as well as the overall stance of your art, seems to aim to profoundly communicate experience. So while we do not have your experience as it was in the real time of making the video, it is still more than our experience of an artwork; you become this portal through which we pass to have our own experience in real time. At the same time you are a conduit for others' experience, the needle through which they pass, the empathetic locus. And like Buddhism, these works are about relationality, not just of human beings but among all beings and with nature. -

Kimsooja

I did another performance called A Needle Woman at Kitakishu in Japan, laying down my body on a limestone mountain, the front of my body away from the viewer. Nothing changes in this video except the natural light from the sky and a little bit of breeze, and at the end there is one fly that is just passing by against the slow movement of the clouds. Of course, I had to control my breath, so my shoulders wouldn't move; I taught myself how to breathe with my stomach. I was there a pretty long time. The rock was a little bit cold, but it was just so peaceful. I was completely abandoning my will and desire to nature and I was at such a peace. There is one face of nature that caresses the human being in the most harmless way. So we feel at absolute peace in this mild nature. Of course, when it becomes harmful, nothing can compete with its absolute damage. -

In a way this work looks a little bit like the reclining Buddha, parinirvana; but, abandoning my ego, at the same time, in a different way, I consider it as a form of crucifix. My body is located at the central point of four different elements which are in-between the sky and the earth, nature and human beings. I located myself on the borderline of the earth and the sky, facing nature and away from the viewers. In the beginning of the video I think my body looks fragile and dramatic, feminine and provocative: an organic body or a body of desire. Over time, I find that my body, with its duration of stillness — breathing in the rhythm of nature — becomes a part of nature as matter itself, neutral, a transcendent state. To me it is like offering and serving my body to nature.

-

Mary Jane Jacob

Has performance become an actual practice of meditation for you, focusing and centering, to attain something for you, perhaps enlightenment, as well as give an experience to the viewer? -

Kimsooja

For me, the most important thing (to arise out of) these performances is my own experience of self, and awakenness, rather than the video as an artwork. That's how I continue to ask deeper questions to the world and to myself. That is the enlightenment I encounter while doing this kind of performance. One such experience occurred with A Laundry Woman — Yamuna River, India (2000) I was just looking at some different locations for a performance, but when I passed by this riverside, I immediately felt the energy and decided, “Let's do it.” Again I put my back to the viewer and looked to the river. It was right next to the cremation place on the Yamuna, so the floating images on the surface of the river were all flowers and debris from cremations. While I was facing the river, I was actually looking at anonymous people's life and death, including mine. It was a purifying experience, praying and celebrating. There's a lot of detail on the surface of the river, so I consider this piece as a painting. It's all reflection: there is no sky, but it looks like sky; there are no real birds passing, only reflections of birds from above. So, in a way, the river functions as a mirror of reality. -

I decided to be there until the limit of my body. I was there for almost an hour in total. In the middle of standing there, I was completely confused: is it the river that is moving, or myself? My sense of time and space were turned completely upside-down. I was asking and asking and asking again, is it the river or myself? I finally realized that it is river that is changing all the time in front of this still body, but it is my body that will be changed and vanish very soon, while the river will remain there, moving slowly, as it is now. In other words, the changing of our body into a state of death is like floating on the big stream of river of the universe. Doing this performance gave me an important awakenness. It suddenly reminded me of one unforgettable dream that I had in my early twenties. I was looking down at Han River from a hillside in Seoul. After looking at the surface of the river for some time, my vision was fixed on the river and the movement of water inside it, showing me the bottom of the river with sand and round stones. Then I started seeing the dancing and spinning stones touch and hit together, mashing and breaking them into pebbles and dust, which eventually will become part of the river itself: "Stone is Water, Water is Stone!" I screamed in the dream and woke up being shocked by this awakenness as if my brain was hit by a strong metal bell.

-

Mary Jane Jacob

Your awareness of the impermanence of all things and embodiment of compassion--which is key to the teachings of Buddha--have brought your earlier expressions of healing to another level. I now recognize that this was at the root of our work together for the Spoleto Festival USA in 2002: Planted Names--four unique carpets at the 1742 Drayton Hall, bearing the names of enslaved Africans and African-Americans who built and cultivated this Palladian plantation--and A Lighthouse Woman in which you used the Morris Island Lighthouse. -

Kimsooja

When I was filming A Needle Woman in Lagos, I happened to visit to an island offshore from which slaves were put on ships to cross the Atlantic Ocean. Standing there, looking out, I could feel the enormous pain of those who departed. The horizontal line of the ocean looked like the saddest line I had ever seen in my life. Then when I visited Drayton Hall and learned about the history of African-American slaves from the other side of the Atlantic Ocean, I immediately saw this plantation site as a vast carpet where enslaved bodies were embedded. There are so many sad stories behind these colonial places. Carpets are not about the beauty of an artist's design, but about the labor of the carpet maker, so I chose carpets as the form to celebrate their labor and time. -

In the companion work, I considered this lighthouse on Morris Island as a witness of water, witnessing all the histories and memories standing still there. When I first visited it, I was so impressed by this lighthouse's loneliness. I related its loneliness to a woman's body and to women who wait for their sons, lovers, brothers and fathers to come home from the sea, who stand by the sea, waiting for them. I programmed a one-hour sequence of nine saturated colors that illuminated the whole tower, spilling onto and reflecting in the surrounding water, changing its rhythm as if it was breathing with the same rhythm of the ocean tides — in and out, inhale and exhale. It wasn't captured in video this time: it was important to experience in the site with the sound of the waves, and the air, and the real sequence of the rhythm of change. I miss the lighthouse.

-

Mary Jane Jacob

Yvonne Rand has spoken about how we can develop our capacity to be with suffering, as it arises, by developing our ability to be in attention. A way to develop this capacity is to continually, over and over, come back to the posture of the body that goes with being in attention. This arrangement of the body entails having the three energy centers in the torso in alignment: the head energy center for perception, the heart energy center for emotions, and the energy center in the belly, the hara, for spiritual strength and stability. When these three energy centers (located in the center of the body just in front of the spine) are lined up, then one is in the posture of attention or presence. This centered posture, in combination with a breath, allows one to be present. When I am fully present, in the moment, I can then be in the field of energy that I stand in with others. Here, in this field, I can more easily put myself in another's shoes, imagine their point of view--not in the "either/or" way of thinking but "both/and": I can hold both what is true in my experience and what is so for the other person. This is what it means to be present and, out of that, to have the skillfulness to develop the capacity to experience another person's suffering. So, Yvonne recognized that you had developed your capacity to become present in your breath with your own suffering as it arose and fell, and simultaneously experiencing the suffering of others, not as separate from yourself but as one: as you stood at the shore of the Yamuna River, on that coast of the island off Lagos, and in the Lowcountry of South Carolina.

-

— From the book 'In the Space of Art: Buddha and the Culture of Now', 2004:

-

Mary Jane Jacob is an independent curator whose exhibition programs test the boundaries of public space and relationship of contemporary art to audiences. She has worked closely with artists creating over 50 exhibitions and commissioning over 100 new artists' projects as chief curator at MCA/Chicago and MoCA/Los Angeles; as consulting curator for Fabric Workshop and Museum/Philadelphia; and for such public projects as "Places with a Past" (Charleston, 1991), "Culture in Action" (Chicago, 1993), "Points of Entry" (Pittsburgh, 1996), and "Conversations at The Castle" (Atlanta, 1996). Currently, she is curator for the Spoleto Festival USA's ongoing "Evoking History" program in Charleston, South Carolina. She is co-editor of an upcoming recent book — Buddha Mind in Contemporary Art (University of California Press, fall 2004) — for which she has conducted insightful with a dozen leading figures about their artmaking practices. This volume is the culminating work of "Awake: Art and Buddhism, and The Dimensions of Consciousness", a consortium research effort based in the Bay Area, which she co-organized. Ms. Jacob is Adjunct Professor at The School of the Art Institute of Chicago and on the adjunct faculty of Bard College's Graduate Center for Curatorial Studies in New York.