2012

Chiara Giovando │ The Unaltered Reality of the World

2012

René Morales │ Kimsooja: A Needle Woman

2012

Antonio Geusa │ Calm Chaos: Kimsooja's Earth – Water – Fire – Air

2012

Laeticia Mello │ The pilgrimage of our own existence

2012

Ricky D'Ambrose │ Kimsooja, To Breathe: Invisible Mirror/Invisible Needle

2012

Choi Yoonjung │ Interview

2012

최윤정 │ 인터뷰

2012

Suh Young-Hee │ Kimsooja: Contemplation on top of the Horizontal and Vertical System

2012

서영희 │김수자: 수직과 수평 체계 위에서의 사유

2012

Bak Sang Hwan │ Cultural Memory, Cultural Archetype and Communication

2012

박상환 │ 문화기억과 문화원형 그리고 소통

2012

Jinkyung YI │ Nomadism: Elements of Nomadic Life and Art

2012

이진경 │ 노마디즘: 유목적인 삶과 예술의 성분들

2012

Choi Yoonjung │ Kimsooja's <A Needle Woman>, Sacred Ritual

2012

최윤정 │ 김수자의 <바늘여인>, 성소적 의식

2012

로자 마르티네즈 │ 사라지는 여인

2012

Rosa Martinez │ A Disappearing Woman

2012

잉그리드 코망되르 │ 김수자: 검은 심연, 명상적인 사라짐, 그리고 우주적 거울로서의 자연

Kimsooja, Bottari Truck - Migrateur, 2007, Single Channel Video, silent, 10:00, loop, performed in Paris, Commissioned by Musée d'Art Contemporain du Val-De-Marne (MAC/VAL)

Kimsooja, Bottari Truck - Migrateur, 2007, Single Channel Video, silent, 10:00, loop, performed in Paris, Commissioned by Musée d'Art Contemporain du Val-De-Marne (MAC/VAL)

The Unaltered Reality of the World

2012

-

Chiara Giovando

I just arrived on the island of Møen in Denmark, where your work will shortly be shown. Last night I spoke with a young Swedish traveler and he said, “I am interested in learning everything by doing nothing.” His statement brought your practice to mind. You have made a series of performance videos that elaborate on each other. A Beggar Woman (2000–2001), A Homeless Woman (2000–2001), and A Needle Woman (1999–2001, 2005, 2009): all present stillness in the midst of chaotic activity. In the latter you inhabit a fixed performative posture within various urban environments, blurring the boundaries between private and public space. In a sense, your body seems to be the place that you inhabit. Could you speak about the relationship between the place of the body (the performative posture) and the geographical place? -

Kimsooja

You can imagine zooming in, the way a needle engages with a piece of fabric. My body’s mobility comes to represent its immobility, locating it in different geographies and socio-cultural contexts. Immobility can only be revealed by mobility, and vice versa. There is a constant interaction between the mobility of people on the street and the immobility of my body during the performance, depending on the society, people, nature of the city and the streets. Different elements inhabit the site as the qualities of the city and the presence of my body appear as an accumulated container of my own gaze toward humanity, and other gazes reacting to my body. While the decision of the location is based on research of its populations, conflicts, culture, economy, and history, the idea of the immobile performance arrived all of a sudden, like a thunderclap or a Zen moment: the conflict between the extreme mobility of the outer world and my mind’s silence coalesced in my body. I always had the desire to present the unaltered reality of the world, by presenting bodies, objects, and nature without manipulating them or making something new. Instead, I want the audience’s and my experiences to reveal new perceptions of the reality of the world and our existence. I pose ontological questions by juxtaposing my body and the outer world in a relational condition to space/body and time/consciousness. -

Chiara Giovando

Your video Bottari Truck – Migrateurs (2007) and the sculptural work Deductive Object (2007) will both come to Kunsthal 44 Møen. Both of these works include bottari. In your work Bottari appears as brightly colored fabric bundles, loaded onto carts or trucks, or placed on the floor. The different contexts draw out various metaphors, representing a journey when loaded on a truck, or exile when displayed half-open and scattered. Once you said, “The body is the most complicated bundle.” What are the imagined and symbolic contents of these bottari and how do they relate to the body? -

Kimsooja

In modern society, bottari (bundles in Korean) have changed into bags; they are the most flexible container in which we carry the minimum of valuables, their use is universal throughout history. We hold onto precious things in dangerous times, such as war, migration, exile, separation, or during an urgent move. Anyone can make a bottari using any kind of fabric. However, I’ve been intentionally using abandoned Korean bedcovers that were made for newly married couples, covered with symbols and embroideries and mostly wrapping used clothing inside—these have significant meanings and questions on life. In other words, my bottari contains husks of our bodies, wrapped with a fabric that is the place of birth, love, dream, suffering, and death—a framing of life.

While a bottari wraps bodies and souls, containing the past, present, and future, a bottari truck is more a process than a product, or rather it oscillates between process and object as a social sculpture. It represents an abstraction of the individual, of society, of time, and memory. It is a loaded self, a loaded other, a loaded history, and a loaded in-between. My Bottari Truck is an object operating in time and space, locating and dislocating ourselves to the place where we came from, and to where we are going. I consider a Bottari as a womb and a tomb, globe and universe. Bottari Truck is a bundle of a bundle of a bundle, folding and unfolding our mind and geography, time and space. -

Chiara Giovando

Sewing into Walking (1995) is dedicated to the victims of Gwangju. In this work, piles of clothing and fabric covered the ground and the Bottari were scattered. -

Kimsooja

It’s a metaphor for the victims of Gwangju uprising in the mid-1980s. The bottari represent people with no power and those forced to remain silent. -

Chiara Giovando

There seems to be both very private and public aspects to your practice. Many of your early works are meticulously sewn, an activity both intimate and meditative. Yet in your films you work with large crews in public spaces. How do these two methodologies affect your process? -

Kimsooja

I made the sewn works alone in my studio; the A Needle Woman performances were shot spontaneously, inserting myself into the general public. I traveled alone to meet people in about fifteen large cities on different continents—except Shanghai and Cairo where I couldn’t easily find a videographer in time. It was not always safe and easy. I am the only witness to all of my performances. -

Recently, I started making a film series, Thread Routes (2010–), shot on 16mm film in many locations of different continents. It’s not about my own experience, but instead other men and women who performed the needlework and threadwork respectively. For this project I had to work with a team. It’s been very inspiring for me to work with a team and travel together, communicating with the group. I’ve learned from them and their research. It’s a different process of production, requiring me to work toward an objective, with a collective way of seeing revealing production process. But in the end it is still an intimate process, where I can revise through editing—that is the next step in the process.

-

Chiara Giovando

The sculpture Encounter – Looking into Sewing (1998–2011) is also a part of your show at Kunsthal 44 Møen. In this work a mannequin, beneath layers of fabric, stands in for a body. Can you tell me about your concept, what happens when this work is looked “into”? -

Kimsooja

It originated with an installation I made in the Museum Fridericianum, Kassel, 1998, for the exhibition Echolot, also curated by René Block. I conceived the work as a performance, but without any performing. An immobile mannequin was fully covered with used Korean bedcovers, and I documented the performative actions made by the audiences, who tried to locate the covered figure. Thus, a visible and invisible interaction is happening, peeling off the fabric by looking. I consider this “invisible sewing.” -

I wanted to create a tension between the audience and the ambiguous figure, the sculptural object. The audience looked at this figure waiting for a performance—but of course there was no movement. I used the immobile figure as a performer for the first time, before using my own body, without planning, A Needle Woman performance at that time, so the audience members themselves become the performers, through their own curiosity and reactions.

This piece is one of the earliest manifestations of the ideas that led to A Needle Woman. It’s a fundamental moment: a strange encounter occurs between the figure and the audience, marked by this intense gaze.

— Kimsooja: Interviews Exhibition Catalogue published by Verlag der Buchhandlung Walther König in association with Kunstmuseum Liechtenstein, 2018, pp.151-154.

-*This is the revised version of the unpublished interview conducted on the occasion of the exhibition Kimsooja at Kunsthal 44 Møen, Askeby, Denmark, in 2012. It is published here with the kind permission of Chiara Giovando.

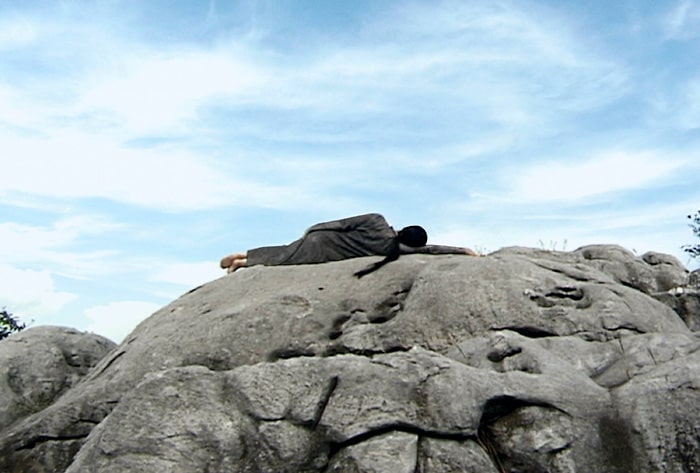

A Needle Woman, 1999 – 2001, video still from Delhi, 8 channel video projection, 6:33 loop, silent

A Needle Woman, 1999 – 2001, video still from Delhi, 8 channel video projection, 6:33 loop, silent

Kimsooja: A Needle Woman

2012

-

A woman stands on the street, immersed amid a torrent of passersby, utterly motionless -- a needle sewing through the fabric of humanity. With a simple, stoic gesture, Kimsooja vividly embodies the struggle to preserve a place for the individual within society, using her body as a conduit for critical questioning. This struggle is a perennial one, but by situating herself in an array of urban centers that span the planet, she imbues it with the tenor of contemporaneity: for if there is a single experience that can be said to exemplify the urgent conditions of today's world, it is the state of being engulfed by the "global city."

-

This first version of A Needle Woman was created between 1999 and 2001. Approximately six years later, a silent but momentous event occurred: For the first time in history, the world's urban populace outnumbered the rural one. [1] Over the last 30 years, urban populations have reached staggering proportions, and their rates of growth are accelerating exponentially. In 1900, only 10% of the world's population lived in cities. Today the figure has climbed above 50%; by 2050, it will represent three-fourths of humanity. [2]

-

A Needle Woman was produced just as the full realization of this explosion of urbanization reached a fever pitch, spilling across a variety of academic disciplines as well as art and popular media. The work is particularly emblematic of the directness with which the phenomenon tended to be addressed at the turn of the new millennium. With the benefit of a little more than ten years' hindsight, it is all the more striking for how it remains relevant to the discourse that developed in the wake of those confrontations.

-

One of the most important of these discursive evolutions involves the way in which urbanism has grafted onto globalization studies. It was the rise of mega-cities throughout the world that made it no longer necessary to abstractly theorize that globalization is happening. Indeed, urbanization is increasingly seen not as an after-effect of globalization, but as its primary driving force. [3] Over the last three or four decades, the increased number and scale of cities capable of participating in the production and management of global flows of goods and capital have led to a vast expansion of those same flows. At the same time, they have produced significant populations of middle-class, cosmopolitan individuals, while mobilizing large numbers of migrant workers from the countryside as well as immigrants from poorer places. The result has been the development of cities bearing unprecedented levels of heterogeneity. The urbanization of the globe has turned out to be inseparable from the globalization of the urban.

-

The nuance and poetry with which A Needle Woman captures these complex dynamics belies the precision with which it communicates meaning. This is especially so with respect to the artist's deliberate selection of the eight sites that "pass through" the anonymous, solitary figure. The academic literature on global urbanism provides a useful entry point (one of many) through which to access the implications that arise from this particular grouping of cities. Viewed in this light, the work bears a particularly strong resonance with an important theoretical framework known as the "global city" paradigm, as well as with the critiques to which it has been subjected. Originally advanced by the urban scholar Saskia Sassen in the 1990s, this approach focuses on how specific urban centers interface with and influence the world economy, using a series of measures such as monetary exchanges, volume of trade, and the number of transnational corporations based in a given urban zone as a way of quantifying its degree of "structural relevance" within a hierarchy of cities. From this perspective, the inclusion of New York, London, and Tokyo in A Needle Woman would serve to represent the traditional command centers of the global economy. Shanghai would serve to indicate the elite class of ascendant hubs that have established themselves more recently as major financial players. Mexico City, Delhi, and Cairo might stand for the crucial "second-" and "third-tier" cities that have also managed to lay a significant claim on the global financial sphere, though at a lower level.

-

While there can be no doubt that the "global city" rubric has produced invaluable insights, in its earliest manifestations it met with heated criticism, especially from the direction of the "Global South" -- that is, from beyond Europe and North America. [4] By prioritizing economic criteria, the methodology involved in this concept had the effect of placing limits on the types of questions that were asked. Indeed, by reducing a city's relevance to its contribution to the world's financial system, it had the effect of focusing the attention of researchers onto a limited number of cities -- perhaps 30 or 40, all but three or four of them in the developed world. Advocates of these critiques also remind us of the importance of more grounded and culturally oriented lines of investigation through which we might uncover valuable means for improving city life -- from the creative productions of Rio's favela architecture, to the vibrant informal economies of Mumbai, to the socially cohesive effects of local popular culture in Kinshasa.

-

With this debate as backdrop, A Needle Woman delivers a keen insight through the inclusion of an eighth site that paradigmatically represents the reverse side of the forces of global urban change: With a population that has escalated from 300,000 in 1950 to one that is estimated to top 23 million inhabitants by 2015, the city-region of Lagos exemplifies the lot of urban agglomerations that have witnessed astonishing growth in the context of severe poverty. [5]

-

In human terms, mass urbanization has had its most powerful effects in the poorest parts of the world. Here again, the rate of the transformations is staggering: Today, about 70% of city dwellers live in developing countries, compared with less than 50% in 1970; by 2030, roughly four out of five urbanites will reside in the developing world. With much of this growth playing out against city infrastructures that remain ill-equipped to handle such expansion, unprecedented numbers have come to inhabit what are typically described as "slums." In the least developed countries, the proportion of slum residents approaches 80% of the populace; already, this figure represents one-third of the total global urban population. [6] While it is important to resist the chronic tendency to reduce the complexity of informal settlements to a single, homogenized vision of Dickensian bleakness, it is difficult not to read such mind-boggling statistics without being struck by the sense that we are in the midst of a crisis.

-

In the face of these and other challenges, a pressing need has arisen to focus at least as much energy on understanding the specific and differentiated local repercussions of globalization as on identifying the resonant scenarios that it creates throughout the world. It has become vitally important, in other words, to survey this global age from the level of the street, the neighborhood, the city, where we may hope to find concrete ways both to maximize its potentials and to mitigate its most distressing symptoms.

-

It is precisely in this sense that A Needle Woman seems so well attuned to the exigencies of the global-urban era. The figure that appears in these images confronts head-on the fearsome power of the contemporary city. At the same time, through her stillness, she expresses the possibility of making peace with it. It is worth paying attention to the mixture of resoluteness and humanism with which she looks forward to the volatile century that stretches out before us.

[Note]

[1] United Nations HABITAT Office, 2006 report.

[2] Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic, eds. The Endless City: The Urban Age Project by the London School of Economics and Deutsche Bank's Alfred Herrhausen Society, pg. 9. New York: Phaidon Press, 2007.

[3] This paragraph is indebted to J. Miguel Kanai and Edward Soja, "The Urbanization of the World," in The Endless City, pgs. 54-69.

[4] See Jennifer Robinson, "Global and World Cities: A View from off the Map" in International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 26.3, September 2002, pgs. 531-554; as well as Kris Olds and Henry Wai-Chung, "Pathways to Global City Formation: A View from the Developmental City-State of Singapore" in Review of International Political Economy 11:3 August 2004, pgs. 489-521.

[5] Mike Davis, Planet of Slums, pg. 15. London: Verso, 2006.

[6] Davis, pg. 51.

- — Preface of the Exhibition 'Kimsooja: A Needle Woman' from the artist's solo show at Miami Art Museum, Miami, USA, 2012.

Aire de Tierra / Air of Earth, 2009, 06.25 loop, sound, still from Earth – Water – Fire – Air, 8 channel video projection, Commissioned by Hermes Foundation, Paris

Aire de Tierra / Air of Earth, 2009, 06.25 loop, sound, still from Earth – Water – Fire – Air, 8 channel video projection, Commissioned by Hermes Foundation, Paris

Calm Chaos: Kimsooja's Earth – Water – Fire – Air

2012

-

The modern artist is living in a mechanical age and we have a mechanical means of representing objects in nature such as the camera and photograph. The modern artist, it seems to me, is working and expressing an inner world – in other words – expressing the energy, the motion and the other inner forces.. ..the modern artist is working with space and time, and expressing his feelings rather than illustrating. [1] — Jackson Pollock

-

In the preface to the second edition of his collection of poems "Lyrical Ballads" William Wordsworth asks a simple yet crucial question "What is a Poet?" The answer he gives is probably the most truthful ever given: "He is a man speaking to men: a man, it is true, endowed with more lively sensibility, more enthusiasm and tenderness, who has a greater knowledge of human nature, and a more comprehensive soul, than are supposed to be common among mankind; a man […] who rejoices more than other men in the spirit of life that is in him; delighting to contemplate similar volitions and passions as manifested in the goings-on of the Universe[.] [2]

-

Kimsooja's work as an artist is constant proof that she perfectly embodies Wordsworth's definition of a Poet. At the core of her production there is always a physical and at the same time metaphysical confrontation between the "spirit of life" that is in her and the "spirit of life" of the world surrounding her. Ultimately, her art is the result of using her body, the shell of her "comprehensive soul", to achieve a balance in the connection of inner and outer life. To quote Kimsooja's own words, her body is the "medium, mystery, hermaphrodite, abstraction, barometer, and shaman" [3] uniting her with the essence of the world. It is charged with and releases spiritual power. All her works, from 2727 kilometres Bottari Truck (1997) to A Needle Woman (1999-2001, 2005), from A Beggar Woman (2000-2001) to A Mirror Woman: The Sun & The Moon (2008), to mention just a few, are the visualization of this flow of energy.

-

Even when Kimsooja is not physically present in the work on display in the gallery space, the reality that she offers the viewers is not a mere representation of a given natural phenomenon. It is the result of an interaction between two parts, of an exchange of energies. Her words about that production in which she is not in the frame – "When I disappear, I represent the act of nature more closely. Thus only my gaze becomes active" [4] – are self-explanatory. The objective of the video camera recording Nature is not a mechanical substitute of her eyes or an extension of her body. It is the activator of the gaze, an active participant in the process of capturing the flow of energy running in both directions between the artist and the outside world. It acts like that needle that for the first time made her sense a strong and inexplicable force emanating from her whole body when she was still a child and was helping her mother sewing together different pieces of fabric into a blanket cover. The absence of her body in the final composition of the projected images does not mean that Kimsooja was there, but she is not there any longer. Kimsooja is still there. To a certain extent, her videos are visual correspondents of what a "trace" is in Jacques Derrida's linguistic studies, that is a "mark of the absence of a presence, an always-already absent present" [5] .

-

The Earth – Water – Fire – Air project, started in 2009, is one of those instances in which Kimsooja's body is not visible in the exhibited images. Natural phenomena, or "Beautiful and permanent forms of nature" – the "Lyrical Ballads" once again – are its main "subjects". In the specific, they are video recordings taken on the island of Lanzarote in the Canary Islands and in Guatemala – volcanic landscapes with incandescent lava, the restless sea, millenarian rocks sculptured by time, clouds of pure white on a clear blue sky. The four basic elements essential to both Eastern and Western thought as the basics of life in the Universe are not presented as single units, each of which is independent and isolated from each other. On the contrary, as suggested by the titles of the videos [6] , they are shown in binary combinations, interacting one with the other, flowing one into the other, the same way as the artist did with the space surrounding her when she recorded those images. Clearly, viewers can fully feel the strength of this energy when inside the space where the work – an eight-channel video installation in its current form – is exhibited. Without any doubts, Earth – Water – Fire – Air is first of all a work that has to be experienced. The intensity of the bond between the artist and the visible objects that she captured with the help of her camera is perceived in the gallery space where viewers are free to move around and use their senses to take in the energy coming out from the screens.

-

It is by experiencing the work as an installation that any possible references to Beauty suggested by the incontestable magnificence of the natural spectacles lose their validity. Beauty is not a keyword here. Surely, a more appropriate approach would be through the concept of the Sublime in aesthetics. To be more precise, the way the Sublime was perceived by the Neo-Kantian school of the beginning of the 20th century according to which the feelings of fear and horror – fundamental qualities for the 18th and 19th centuries (Edmund Burke and the English Romantics, amongst others) – were replaced by a sense of contentment and safety before an object of superior force.

-

Kimsooja stands with her video camera in front of an object of "superior force". The moment she presses the rec button, like a needle piercing a piece of cloth, her "superior force" starts to interact with that of Nature before her. The energy of the exchange is very strong and overwhelming. However, the effect reached – Earth, Water, Fire, and Air displayed in the exhibition space – is indisputably one of ease and wellbeing. Her works are never a methodical process of "quoting" from Nature, simply because Kimsooja is not a passive receiver. The segment called "Fire of Air" can serve as a proof of the artist's dialoguing with Nature. In it, while being driven she operates a spotlight to break the darkness of the night and illuminate the rocky fields of the landscape. Here, she in charge of what can be seen and what stays wrapped in darkness. Because of this constant dialoguing, none of the images offered to the viewers can ever be, to quote Wordsworth again, a "soulless image on the eye" [7] , a mere visual impression on the retina of the spectator. On the other hand, Kimsooja sublimates the etymological meaning of the word "video", that is "I see", first person of the present tense of videre (to see). She invests it with both spiritual and lyrical power. Simply, albeit roughly, put, it is poetry camouflaged as science.

-

As an artist Kimsooja's possess the unique ability to turn the chaos of energy exchanging during the time of performing or recording – that "spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings" [8] between the Poet and Nature – into a sense of tranquility and calmness for the viewers. Accordingly, the screens framing the videos lose their boundaries and a distinct feeling of oneness with Nature is strongly felt. To a certain degree, the genesis of Earth – Water – Fire – Air is not that dissimilar to that of Jackson Pollock's canvases. It is the same intensity of human artistic energy – albeit different in nature. Obviously, the outcome is at the antipodes. Kimsooja's is a calm chaos generated by the maturity of the passions of the artist's heart. And it is this proven maturity that, paraphrasing Pollock when he was asked if he worked from Nature, allows to state that Earth – Water – Fire – Air proves once and for all that Kimsooja is Nature.

[Note]

[1] Pollock, Jackson. Interview by William Wright, Summer 1950. Quoted in Clifford Ross (ed.), Abstract Expressionism: Creators and Critics, Abrahams Publishers: New York, 1990, pp. 139-140. > return to article >

[2] Eliot, Charles William (ed.). Prefaces and Prologues. Vol. XXXIX. The Harvard Classics. New York: P.F. Collier & Son, 1909–14; Bartleby.com, 2001. www.bartleby.com/39/. 2 May 2012. > return to article >

[3] Kim, Sung-Wong, "About Nothingness: Being Nothing and Making Nothing". Official internet site of Kimsooja. www.kimsooja.com/texts/sung_won_kim_EWFA_2009.html. 2 May 2012. > return to article >

[4] Commandeur, Ingrid. "Black Holes, Meditative Vanishings and Nature as a Mirror of the Universe". Kimsooja – Windflower: Perceptions of Nature (Catalogue). Kroller Muller Museum, The Netherlands. Interview with the artist by the author, November 2010. > return to article >

[5] Macsey, Richard and Eugenio Donato (eds). The Languages of Criticism and The Sciences of Man: the Structuralist Controversy. JHU Press: Baltimore, 1970, p. 254. > return to article >

[6] n its current version Earth – Water – Fire – Air comprises the following eight videos: “Fire of Earth”, “Water of Earth”, “Fire of Air”, “Earth of Water”, “Air of Fire”, “Air of Earth”, “Air of Water”, “Water of Air”. > return to article >

[7] Wordsworth, William. The Complete Poetical Works. London: Macmillan and Co., 1888; Bartleby.com, 1999. www.bartleby.com/145/. 2 May 2012. > return to article >

[8] Eliot. > return to article >

- — Essay of the Catalogue, 'Calm Chaos: Earth - Water - Fire - Air - Kimsooja' from the artist's solo show at the Museum of Contemporary Art PERMM, Rusia, 2012.

The pilgrimage of our own existence

2012

-An art where nomadism and the relation with the other reveals the importance of mankind and the contemplation of the reality that we live in.

-

Kim Soo-Ja is her full name, but she introduces herself in her web page as Kimsooja (Korea, 1957) with her own manifesto: In "A One-Word Name Is An Anarchist's Name" (2003), Kimsooja refuses gender identity, marital status, socio-political or cultural and geographical identity by not separating the family name and the first name. In this same way – without an identity or with an almost ephemeral one – she has been developing since 1992 her singular and poetic work that includes videos, performances, installations, site-specific projects and photographs.

-

To give rise to her work, Kimsooja travels to different cities, villages and small towns in search of diverse cultures. It is a pilgrimage with bottaris – Korean word that means "wrapping luggage with a wrapping cloth", the easiest and most functional way of carrying one's belongings– sometimes walking and others by truck; a nomadism that speaks about civilizations, traditions, and languages that shall be faced in the new crossing.

-

The art that she creates becomes ceremonial. She looks through her own past, present and future and through that contemplation the questions and discourses on time and space emerge. This way, Kimsooja links her work to nature and the relation with others. In her pieces the viewers are engulfed by the multiple perspectives introduced by the artist and they can participate of it lively.

-

Textiles are the media that Kimsooja chooses to develop her maps of beliefs. Despite her origins where there always existed a need of experimenting different types of media similar to fabrics, sewing became the wisest and most accurate tool. It allowed her to combine her questionings and the relation between the "I" and the "Other" over the canvas surface. Thereby, the separation between the artist and the surface disappears and transforms into a healing joint.

-

Bottaris are probably the most distinctive element in Kimsooja's art. They hold not only references to the migration of her land but also to the essence of all her work: mankind. "I've always been fascinated by nomadic minorities' life style and their rich visual culture and originality. During my youth my family also lived a nomadic life due to my father's job, although within Korea. I wasn't aware of the fact that my family had been wrapping and unwrapping bottaris all the time until I started Cities on the Move–2727 km Bottari Truck in 1997", she explains.

-

Kimsooja's bottaris are sculptural pieces. Viewers can open, touch and examine them. The artist acts as an intermediary between the owners of those clothes and old bedspreads and the observers. As they make contact with the bottaris, they embark on their own journey imagining who used these fabrics before. This way, the pieces transcend the Eastern tradition and the historical codes that were associated to them; they become channels which redefine the concept of the object. Here it doesn't matter if Kimsooja re-makes and re-contextualizes a ready-made but the way she chooses to look at her past and the transition that Korea lived from a traditional lifestyle to a modern one.

-

A Needle Woman, A Beggar Woman and A Homeless Woman are the most developed and delicate performances by Kimsooja. In them, she appears with a singular hieratic posture amongst a crowd in continuous flow that walks towards and by her sometimes observing and others questioning themselves the truth of her static stance. Anonymous and with neutral clothing, she achieves to interfere with the canons and flux of the city with one unique message: temper and truth.

-

The patience and austerity that the artist uses to introduce folklore and daily habits of Asian and Latin-American cultures in her videos is what lets her bonds so closely to their respective traditions. Each folkloric practice that Kimsooja discovers works as a talisman. First she researches the origins and encounters of the culture and then she charges herself with figures of power.

-

The spectrum and repetition which Kimsooja works with in her videos is expressed by the cities in move, in an action loop. In Thread Routes (Chapter 1. Peru) – a video that captures the routes of the threading women in Peru –, women weave again and again the colorful embroideries of their origins where generations and spiritual experiences are combined together. Mumbai: A Laundry Field was filmed in India where men shake, drain and strain against the stones the symphony of tonalities of their clothes. They are the representation of time, an intangible and unapproachable mental space, never planned.

-

"When it comes to the performative video pieces such as A Needle Woman performance series, I just had a strong desire to do a performative piece but didn't know what exactly it would be, even until the moment I started filming", Kimsooja says. That is the main reason why intuition plays such an important role in the process and meaning of her work. She rises as a medium woman, as an ethnographic canal that lets the world see the most pure forms of art. A reader of the visible and invisible worlds given by nature.

-

These projects have turned Kimsooja into one of most renowned and interesting artists from the international contemporary panorama. She lives and works in New York, and has exhibited her projects and artworks all around the world. Among them latest ones we can name NPPAP - Yong Gwang Nuclear Power Plant Art Project, commissioned by The National Museum of Contemporary Art (2010), Earth – Water – Fire – Air, Hermes (2009), Kimsooja, Baltic Center (2009) and Lotus: Zone of Zero, BOZAR, Brussels (2008), as well as other emblematic ones like Artempo: where time becomes art (2007) presented at the Venice Biennale, Cities on the Move (1997-2000) and Traditions/Tensions (1996-1998), and the participation in other biennales like Moscow (2009), Whitney Biennial (2002), Lyon (2000), São Paulo (1998), to name some.

-

Kimsooja has been working for two years on a series of a 16 mm film project called Thread Routes. She has completed the Peruvian chapter on weaving culture and the European chapter on lace making is being developed. The project about origins of textile culture includes India, Mali, China, and Native America.

─ Arte Al Limite, March 2012, pp. 30–38

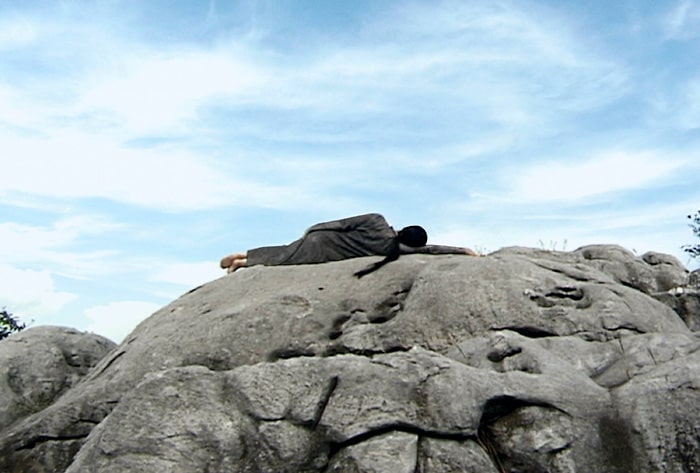

A Needle Woman, 2005, Sana'a (Yemen), one of six channel video projection, 10:40 loop, silent

A Needle Woman, 2005, Sana'a (Yemen), one of six channel video projection, 10:40 loop, silent

Kimsooja, To Breathe: Invisible Mirror/Invisible Needle

2012

-

From blue to violet. The nine minutes of To Breathe: Invisible Mirror/Invisible Needle involve a lifecycle of the color spectrum, an electronic spiritual autobiography of red-yellow-blue sanctified at the four hard edges of the screen. These are colors that command, rather than pacify, the eye; the problem, to borrow Duchamp's phrase, of being "up to the neck in the retina," here becomes a compelling visual solution, an optical tease with metaphysical consequences. "My motivation for creating this piece was to question the depth of the surface," Kimsooja has said. "Where is the surface? What in the world is there between things?"

-

These migrating color fields, these on-screen anti-surfaces, frustrate the eye, if only temporarily; the effort here is to re-educate our visual intelligence, to make the eye more buoyant, less habituated. What Kimsooja calls her interest in in-betweens – in those enigmatic medial spaces that can be intuited but never experienced simultaneously – gives this work its itinerant sensibility, and it is this skepticism of the surface that disaffiliates To Breathe from a mid-twentieth-century aesthetics apotheosized by Barnett Newman, Ellsworth Kelly, Anne Truitt, Robert Ryman, etc. A more suitable list of aesthetic influences might include: magic lantern shows, Stan Brakhage films, Technicolor, stained glass windows, and also Cézanne, whose attraction to what he called "the meeting of planes in the sunlight" might describe another visual corollary to this work: the sensation, the flicker of colors, produced when staring at the sun with one's closed.

-

The two channels. The inhale-exhale component of the soundtrack forms its metrical unit: the couplet. The rhyming of inhale and exhale is made possible by an activity (breathing) which, in this instance, becomes increasingly less agile, more labored and urgent. Once the last exhale is replaced by the low, monophonic sound of humming, however, we assume that a change in condition has taken place, that a transaction between physical and spiritual experience has culminated in repose. And yet, Kimsooja's colors continue their gestation; the juxtaposition of an uninterrupted, trifurcated human hum and an image with no reliable surface and no discernable visual plane is the technique of a stereoscopic aesthetics. The effort is toward two radically dissociated channels of information that cannot be unified by the eye alone, but that require a bit of imaginative thinking and mental ingenuity to grant their coalescence.

-

But to think imaginatively entails a sensorial leap of faith and a transfiguration of the commonplace that often feels peculiar and difficult, but that is also necessarily clarifying and inventive. Hence the statement by Kimsooja: "I don't believe in creating something new but in inventing new perspectives based on mundane daily life." The result plays like an ecstatic vision; a flash of light and sound that transforms Duchamp's "retinal element" into an instrument – a needle to thread and combine, a mirror to duplicate and rhyme – for achieving the movement from surface to spirit.

─ May 2012

Interview

2012

1.

-

최윤정

I first want to express my gratitude for being part of our opening exhibition. Since this is your hometown, I'm sure this would be a particularly emotional experience for you. Do you mind sharing with us your impression of the participation? Is this your first exhibition in Daegu? -

김수자

I have worked in Daegu, perhaps in the late 70s. It was the 'Daegu Contemporary Art Festival" hosted by Daegu Daily. I was able to work with Kim Yongmin on an event for the occasion. We took the train from Seoul, wore orange vests and went about collecting things without saying a word to each other. We collected anything and everything. The exhibition was at the Maeil Daily Gallery, and our work involved installing collected objects. I remember I made a small stone grave of sort with the pebbles, sand, garlic and tree branches I

found out in the field. So this is the first exhibition since then, and actually a first ever solo exhibition in Daegu. This certainly is an emotional experience, and to be able to meet with the audience and citizens of Daegu through my work makes the exhibition all the more special. -

최윤정

The exhibited work here is 'Needle Woman (2005).' If the first Needle Woman series that took place from 1999 to 2001 were to be considered a kind of sacred ritual wherein the Needle Woman perceives the body as a 'needle' in the midst of the throngs of people, it seems as though the 2005 work confers additional significance. How would you differentiate the two projects? -

김수자

In the early 'Needle Woman' my body would operate as one symbolic needle or medium, a certain 'axis of space.' This is why the sites I sought out were where I could meet many people. Especially in the metropolitan areas like Tokyo, Shanghai, New York and London, my performance was in real-time, carrying out the mind of embracing the people I meet. The 2005 piece exhibited here is similar in that it is also a performance, but this time it is not a performance shown in real-time. Rather, it is in a kind of 'slow-mode' where my body is brought to point zero, now as an 'axis of time.' In other words, it is a work where the temporal difference among my body(Zero-time), slow mode(extended-time) and the audience(real-time), and the changes on the psychological dimension rising from such difference could be explored more in depth. I looked into countries that symbolize factors of conflict in politics, religion, culture and economics; post-colonial Cuba, Chad; poverty-stricken, violence-laden Rio de Janeiro; Sana'a, Yemen and Jerusalem, Israel where religious, cultural conflicts are ongoing; Patan, Nepal where civil war remains. This is based on the very question about condition of humanity. After the Iraq-war, violent crime was rampant in the world. So this work shows a longing for peace. Despite the conflict, discord, poverty and strife, when the performance footage from each city is brought into one space, temporally extended into 'slow-mode,' one realizes that there is human's universal nature to be found. -

최윤정

I'm aware that this work is originally intended to be displayed consecutively alongisde each other on one wall. I would like to hear more about the relation between a work and the mode of installation proper to the work. -

김수자

Every city has its own particular problems, and when these problems are laid out on one wall in one space, and when these are stretched out in time, I believe that real existing problems starts to unravel and become allayed. And what remains is the essential. Perhaps the work would be able to reflect the universality and origin commonly shared by humanity as well as express the possibility of reconciliation. Though it may be ironic to display countries with elements of conflict in allayed form, it contains my intention to portray the horizon of my viewpoint that faces towards the possibility of such a world. So that is an important visual element. -

최윤정

When we look at your work, we start to understand the artist's body displayed as 'axis' and the work's significance through the performance scenes. It's also interesting to note the various responses of the crowd in different countries and cities. I'm sure there were many happenings at the sites of shooting. -

김수자

The work in Yemen, for example, was at a vast marketplace. Many merchants and pedestrians were passing by, and there were a variety of shops including a music shop where they sold CDs and cassette tapes. There was local music being played from the shop, and since I had my back against them I was unaware of what was going on. Behind me was an elderly man dancing with a croissant-like sword which Yemenite men wear around their waists. At a glimpse, the scene may look violent or dangerous, but I was told that the dance was of Yemen's traditional ritual, performed at weddings and festivals. A cultural act characteristic of the place. It was so impressive to me. -

최윤정

Then I'm sure you were exposed to actually dangerous situations. -

김수자

Our work in Patan near Kathmandu, Nepal was during the time of the civil war. Employees of the Korean consulate office and other foreign consulate offices were being told to go back to their countries. I did look into the situation beforehand and concluded that it was not direly dangerous, so I decided to proceed. When I arrived in Kathmandu, armed soldiers were placed in every nook and cranny, and I frequently heard gun- shots from the hotel I stayed. The area was actually the site of ongoing contention be- tween the Maoists and the government, making it, in fact, extremely dangerous. I was also a slum called Rocinha in Rio de Janeiro. Being one of the biggest slums (favela), the area was laden with topless young men with guns around their waists and drug dealers. One day I went up to the rooftop to take a view of the mountainside that was surrounded by houses crammed against each other. Then suddenly I heard gunshots right behind me as well as across from where I was standing. Uneasy about not knowing what was happening, I later found out that it was an occasion where drug dealers exchange signals when conflict is triggered.

2.

-

최윤정

In the process of researching data and references of critical reviews and interviews, I personally wanted to ask this question. There are cases where 'shaman' or 'shamanistic act' is mentioned in relation to your work. I assume that this is largely due to the fact that your performance itself takes on the attitude of a medium, mediating between humans, between worlds. What do you think about this expressions? -

김수자

Well, during the act of wrapping and sewing fabric(or folklore object) of primary, traditional Korean pure colors, there were moments when I felt that the energy I had was shamanistic. But since calling it shamanistic would mean it is a religious activity, I think it is a bit closer to 'Zen' in Buddhism. When I was in Shibuya, Tokyo to carry out my walking performance, I saw throngs of people passing by Shibuya and could not but pause where I was standing, and piles of outcries accumulated within me besieged by like a whirlwind of silence. I'm thinking that to hear that sound might be closer to an act of 'Zen' and that the decisive moment of artistic act occurs from this experience. I believe it is through this that the inexplicable energy and the creative act of the artist as a transcendental act - an act that seems to completely demolish that energy, time and space - could be better explained. -

최윤정

Likewise, what I zeroed in on was the possibility of interpreting this more in connection with the aspect of cultural archetypes and elements of the humanities, rather than with the shaman as an agent. In this respect, the historical origin of shaman in Eastern culture finds its context in Confucian, Buddhist and Taoist thought, also showing parallels to the Confucian sage and the Taoist hermit. This surely isn't a common topic, though very interesting. I'm sure that this also makes the interpretation for the contemporary artist so fertile. -

김수자

Because my work is a result of a general rumination over the problem of how to obliquely present my viewpoint in the larger context of contemporary art history and performance art, thus it requires a consideration of diverse aspects that cannot be tackled merely from the viewpoint of 'shaman,' energy, or spirit-possession. Again, this must be contextualized in contemporary art as well as incorporate different viewpoints, that is, the four points of viewing the world. If I performed the Needle Woman towards four, or eight, directions, there is also Sufism, where the idea that this world-encompassing act is the act of love for mankind and the extent to which this love should reach are expressed in a kind of poetic language. In other words, I am saying that rather than viewing this as one phenomenon in our culture, an attempt to combine complex and multilateral interpretation is needed. The combination of, say, the context of contemporary art, both the position of obliquely expressing the performer's contextual thought and the position of a medium, the position of Zen, Sufism, the cruciform structure in Christianity, the viewpoint on sacrifice, etc. Hence, I believe that it is possible to speak of various viewpoints in a complex manner. -

최윤정

Because your performance incorporates regions of conflict, some might think of your work as a journalistic effort to bring awareness about certain situations. -

김수자

I am not interesting in tools of social change utilized for direct incitement about the situation itself. But I stand in the position of always being conscious of such problems, of looking at the situations and of mediating to help look at the situations. This has less to do with trying to solve the problems through a direct, one-to-one contact with every state of affair than the effort to help immerse oneself in the situation by means of contemplation and taking a transcendental stance. The next depends upon audiences. They will be able to experience each different dimension, following their own memories, sensibilities, and capabilities. -

최윤정

The word 'nomadism' also makes a frequent appearance in references to your work. I was looking at past interviews, and there were no negative mentions in relation to this. I also remember you mentioned this as a 'life style' of the modern man, whereas the critics had no hesitation in connecting nomdaism with bottari(bundles) as a symbol of moving and relocating. At the Whitney Biennale, you wrapped the table with traditional Korean fabric, which was called nomadic (by Yi-Jinkyung). I agree with this view. Rather than bottari symbolizing moving, relocation or sedentism, it seems to be where new values are generated from the collision under a table cloth with traditional patterns, covering self-identity, familiar cultures which have been put in a different culture. -

김수자

Yes, I agree as well. But I also think that the very process of my act can also be considered nomadic. In this respect, whether it is fabric spread out in Whitney Museum or the Bottari truck at the Venice Biennale, are they not all parts of a nomadic act displayed? After all, contemporary people live in a time where living a nomadic life is inevitable. So now nomadism is not close to live in free and easy retirement and echo-friendly but in hectic Urban-global-business as prag- matic meanings. Constantly, world wide-communication and 'omnipresent Nomadism' is rampant. I believe that my work is a natural result of my real-life wrestling with personal problems and agonies. It was not my original intention to fit my work into a specific framework of nomadism or cultural context. -

최윤정

I got the sense that 'Needle Woman' (2005) was in line with your preceding works such as 'Sewing into walking' (1995) that commemorates the victims of the Gwangju massacre, 'D'apertutto or Bottari Truck in Exile' (1999) dedicated to the victims of the Kosovo War, and 'Planted Names' (2002) that recorded the names of the black slaves victimized in the plantations of South Carolina. This aspect was also noted in Oliva Maria Rubio's review. I start thinking that your work might show an activist's appearance already from the very content it contains. -

김수자

That's possible. Some view my work as Minjung art. It isn't entirely wrong, but I believe my work contains both modernism and Minjung art elements. Aesthetically, my work always is in the realm of the abstract(form) and the representational (reality). Thus without connecting a certain collective movement(Modernism or Minjung art) or any other groups, In spite of all this, I adamantly refused to take a political stance, thus independently going about my own way. In the case of Minjung art in Korea, it rises from the basis of the absurdities of the times and political realities, but for me, problems on a more personal level, especially the ontological passion of an individual, self-contradictions and self-love had priority. If those ten-something years of passionate acts of sewing were to be viewed as processes of healing within the self, once the healing was thought to be complete, I turned to the healing of the other. Of course even during the times of sewing, the individual as the 'self' was, let's say, not so much a revealer of some hidden story or identity. Because it was through the borrowing of the other's body, the other's pain that I dealt with my own pains and passions, the physical healing of sewing was transformed into 'Needle Woman,' a way of healing without acting. The idea of the nomadic is also something about emptying your space. It's not about setting your own space and building your own territory. It's about constantly opening and dissolving oneself to another world through self-negation, a constant experience of numerous processes of this sort. -

최윤정

There is, of course a critical consciousness that comes from internal situations as an artist before the needle work times. Such process continues till now, and coupled with 'mediation', you cast it back to the relation between yourself and the world, between humans, all the way to the relation between elements in nature. I want to hear an elaboration on 'relation'. -

김수자

The first work with sewing was actually a visual expression of a certain relation. It is a kind of statement I made as an artist, a statement which I still hold fast to, and through fabric as tableau(surface), needle as a symbolic brush and artist's body. The stage of my work was comprised of a passion for surface I had as a painter, believing that such surface could be the other as well as myself, a kind of 'mirror,' a study of otherness. Thus, the act of sewing is one that traverses the division between the self and the other, for it intends to question and subsequently find the answers to the questions. In this sense, such an act may be considered a personification of the problem of painting in its form. That is, 'surface' became 'character.' Onto-logically it became the 'other,' and in turn occupies an equivalent position as a medium. In terms of the medium, this also made it possible to unfold upon a surface the studies on form as well as questions of mankind and essence. Thus this makes one, not two.

-

최윤정

The breadth of the genres in which you work seems broad, ranging from installation to video and sound. You approach such diverse genres and forms, and I want to know whether there is something you intend to convey in your choice of each genre? -

김수자

Well. When I move from sewing to wrapping objects, and from there to wrapping bottari, the passage is not guided by a kind of logic or preconceived idea but rather by an immediate response. It is an accumulation through an instant impulse, an artistic will that is proper to me. But in retrospect, I certainly see an internal logic or sensibility at work. Thus, the wrapping work was possible because the properties of wrapping were already implicit in the original questions I had towards flatness and the properties of sewing. In other words, such things were naturally unraveling out of my body. As a flat bottari, it was discovered from within me, then naturally connecting to artistic im- pulses. I frequently feel like I am being led by something. Different from intending something, I feel led to a place where I have no other choice but to act, and such an act becomes the ground for the next project. After the bottari project, clues to the problem of ideas and media fitting to the experience of a new space were discovered. For example, what enabled me to think up the weaving sound at a weaving factory was the experience of the weaving factory space at 2004 Lodz biennale in Poland, an empty room similar in structure to this project room. It was a case where I became conscious of my body as it felt like I was hearing the sound of weaving machines where weft and warp intersect. In the end, I realized that our inhalations and exhalations are like weaving, and started puzzling over their meaning beyond mere yin and yang, but its connection to life and death. This is what led me to the sound performance of 'To Breathe.' When it comes to choosing a new medium and intending its application, I invoke a new kind of thinking in the encounters with a new space, new culture, cultural archetype or natural structure. In this sense, rather than merely calling it a discovery of new media/genres, it might be more appropriate to say that the medium is discovered in the process of attempting to deepen the questions and concerns I initially carried. Thus my

selection of a certain kind of medium is triggered by the deepening of the concepts behind my work, not about the medium or genre itself. This is the same with my video work, where the camera lens confers a conceptual meaning in the context of connecting the world and people. -

최윤정

You mainly work abroad. Do you mind sharing your exhibition plans for next year or projects you are either working on right now or are interested in working on? -

김수자

A few solo exhibitions and group exhibitions are planned to take place for next year in Europe, Asia and USA. Especially I have to create the video project for the installation in the IOC Olympic Museum and in the border between Arizona and Mexico commissioned by the USA Government. Thus, next year I will so busy that I cannot take a rest. And another project I am working on right now stands at the antipode of the Needle Woman project. While the Needle Woman work centers on finding the trajectory of the needle, 'Thread Routes' is a 16mm film project which traces the trajectory of the thread. We had better guess the meaning of 'Thread routes' as 'Thread roots'. As the Roots(nature) seems to lead us to the Routes(road) on our necessary journeys.

─ Interview on December 5, 2011. from Exhibition Catalogue 'Kimsooja' published by Daegu Art Museum, Korea. 2012, pp.404-411.

인터뷰

2012

1.

-

최윤정

대구미술관 마지막 개관특별전에 참여해주셔서 감사의 말씀을 드린다. 대구가 고향이다보니 감회가 새로울 듯 한데, 참여에 대한 소감을 부탁한다. 이것이 대구에서 첫 전시인가? -

김수자

이전에 대구에서 작업 한 바가 있다. 아마 70년대 말, 대구일보사에서 주최한 ‘대구현대미술제'로 기억하는데, 그때 김용민 선생과 함께 이벤트를 한 적이 있다. 서울에서 기차를 타고 함께 와서 오렌지색 조끼를 입고 야외를 다니면서 각자 서로 얘기하지 않고 무엇이든 채취를 하는 행위였다. 매일신문사 갤러리에서 전시하게 되었고, 채취한 오브제들을 그곳에 설치하였다. 그때 들에서 주운돌, 모래 그리고 마늘, 나뭇가지들을 가지고서 조그만 돌무덤 같은 것을 만들었던 것으로 기억한다. 그때 이후로 처음으로 대구에서 하는 전시이자 첫 개인전이다. 그래서 사실 감회가 깊고 또한 대구 관객들, 시민들을 내 작품을 통해 만날 수 있는 기회를 갖게 되었다는 점에서 나에게는 특별한 전시이다. -

최윤정

이번 전시작품은 '바늘여인(2005)'이다. 1999년도에서 2001년도 바늘여인 첫 번째 시리즈가 많은 군중들이 집결해있는 장소에서 '바늘'로서 몸을 인식하고 또한 '바늘여인'으로서 행하는 일종의 성소적 의식이었다고 볼 수 있다면, 2005년도 작품에는 또 다른 의미들이 부가된다는 생각이 든다. 작가의 입장에서 두 시리즈 사이의 차이를 설명해달라. -

김수자

초기 '바늘여인'은 내 몸이 하나의 상징적인 바늘 또는 매개체로서, 하나의 '공간의 축'으로 작용한다고 볼 수 있다. 그래서 주로 찾아가 멈추어 섰던 장소는 많은 사람들을 만날 수 있는 거리, 특히 메트로폴리스들(도쿄, 상하이, 뉴욕, 런던 등)이었고, 거기에서 모두를 만나고 그들을 포옹한 마음을 리얼타임 퍼포먼스로 펼쳤다. 2005년도 작품은 같은 퍼포먼스임에도 불구하고, 초기 리얼타임으로 보여지는 퍼포먼스가 아니라, '슬로우 모드'로써 이제는 내 몸을 '시간의 축'으로 삼는다. 그래서 나의 몸(정지의 시간성), 슬로우모드(확장된 시간성), 그리고 관객(리얼타임)의 시간적 차이에서 발생할 수 있는 심리적인 차원의 변화들을 더 심도있게 들여다보는 작업이라고 할 수 있다. 정치나 종교, 문화 그리고 경제 등 갈등적 요인을 상징하는 나라들을 찾아보았다. 포스트콜로니얼리즘에 대한 쿠바, 차드 그리고 빈곤과 폭력 이런 것들에 노출이 되어 있는 리우 데 자이 네이루, 종교적 문화적 갈등을 겪고 있는 예멘의 사나와 또 이스라엘의 예루살렘, 시민전쟁 등이 벌어지고 있던 네팔 파탄. 이것은 인간의 조건(condition of humanity)에 대한 의문을 바탕으로 한다. 이라크 전쟁이후 혼란과 폭력이 난무하는 세계 속에서 평화를 갈망하는 작업이기도 하다. 분쟁과 불화와 빈곤과 갈등 그럼에도 불구하고 '슬로우 모드'로 시간을 연장시킴으로써, 각 도시들이 한 공간에 놓여있는 경우, 그 속에서 우리는 인간의 보편적인 본질을 발견할 수 있다. -

최윤정

원래 이 작품은 벽면에 모두 함께 연속적으로 설치되는 형태를 갖는다. 작품과 고유한 설치 방식이 갖는 연관성에 대해 좀더 이야기를 듣고 싶다. -

김수자

사실 각 도시들은 각기 다른 특징적인 문제들을 안고 있다. 그것들이 한 벽면에 한 공간에 놓여져 있을 때, 그리고 그 시간을 슬로우 모드로 표현해 보일 때, 실재하는 문제들이 유화되어 풀어질 수 있다고 본다. 그러고 나면 남는 것은 가장 본질적인 모습이라고 생각한다. 그것이 어쩌면 인류 전체가 갖고 있는 보편성과 원형성을 비추고, 또한 화해할 수 있는 가능성을 표현할 수 있다고 보는 것이다. 갈등적 요소를 가지고 있는 나라들을 유화된 모습으로 함께 보여준다는 것이 아이러니하기도 하겠지만, 사실 그러한 세계를 향하는 내 시선의 지평을 보여주고자 하는 것이 또한 의도이다. 그래서 그 부분이 이 작품의 비주얼한 요소로서 중요하다. -

최윤정

작품을 보면 '축'으로서 보여지는 작가의 몸, 이를 통한 퍼포먼스 장면을 통해 작품의 의미를 헤아리게 된다. 또 한편으로 작품을 감상하다보면 각 나라마다 각 도시마다 군중의 반응이 참 재미나다는 생각이 든다. 촬영현장에서 여러 가지 일들이 많았을 것 같다. -

김수자

예멘에서의 작업을 얘기하자면 내가 퍼포먼스하고 있는 그 거리는 굉장한 시장통이었다. 많은 상인과 행인들이 지나가고 있었고 이제 그 중에는 씨디나 테잎을 판매하는 뮤직숍도 있었고, 거기서 그곳 특유의 음악들이 흘러나 오고 있었는데, 퍼포먼스하면서 뒤돌아 서있었으니 그때는 몰랐지만, 내 뒤에서 어떤 노인이 예멘 남성이 복부에 차는 초승달 모양의 칼을 빼고 춤을 추고 있었다. 얼핏 보면 폭력적이고 위험한 장면으로 생각할 수도 있지만, 그것은

예멘의 전통적인 춤 예식, 결혼식 혹은 축제 때 추는 춤이었다. 그곳만의 문화적인 행위로 나에게는 정말 흥미로웠다. -

최윤정

반면에 직접적으로 위험한 순간에 노출 된 적도 있었는가. -

김수자

네팔 카트만두 인근 파탄에서 작업을 하고 있던 시기는 시민전쟁이 벌어졌던 때였다. 그때 한국영사관, 외국영사관 직원들과 그들의 가족들이 다시 본국으로 돌아가고 그러한 상황이었다. 알아보는 데로 크게 위험한 상황은 아니겠다 판단해서, 떠나기로 결심을 하였다. 카트만두 골목 곳곳에 무장한 군인들이 서 있었고 내가 묵었던 호텔 인근에서조차 총성이 들려왔다. 사실 그 주변에 있었던 마오이스트들과 정부간 분쟁이 끊임없이 이뤄지고 있어서 위험한 상황이었다. 리우 데 자네이루에서는 로시나(Rocinha)라는 빈민촌으로 가장 큰 슬럼가(favela) 중 하나였다. 거의 반라의 젊은 청년들이 양 허리에 권총을 차고 각 골목 코너에는 마약 중개상들이 앉아있기도 하였다. 어느 날 옥상 위에 올라가서 그 빈민촌 주택들이 빼곡히 둘러싸여 있는 산 전경을 보고 있었는데 갑자기 등 뒤에서 그리고 바로 맞은 편에서 총성이 울렸다. 무슨 일이 벌어지는지 몰라 불안하였는데, 알고 보니 마약 중개상들이 서로를 위협하는 총성이었다.

2.

-

최윤정

비평자료들, 인터뷰 자료들을 찾아보고 연구하는 과정에서 내 나름으로 꼭 이 질문을 던져보고 싶었다. 작가 김수자와 작업에 관련해서 '샤먼', '샤먼적', '샤먼적인 행위'를 거론하는 경우가 있다. 아마도 작가의 퍼포먼스가 인간과 인간을 매개하거나 세상과 세상을 매개하는 매개자, 수행이 느껴지는 자세에서 비롯된 것이 아닐까 생각하는데, 이와 같은 표현에 대해서 어떻게 생각을 하는가. -

김수자

글쎄.. 80년대에 아주 원색적인, 한국 고유의 오방색 천들(혹은 민속오브제)을 사용해서 매고 감고 꿰매고 감싸는 행위들을 할 때, 나는 내가 품은 어떤 에너지가 샤먼적이라고 느낀적이 있다. 그러나 사실 샤먼이라고 한다면 일종의 종교적인 행위이고, 오히려 나의 경우는 이를 불교의 '선(zen)'에 더 가깝지 않은가 생각한다. 처음 도쿄 시부야에서 워킹walking퍼포먼스를 하려고 하다가, 어느 순간 시부야의 수많은 인파들이 오고가는 것을 목격하면서, 그 순간 그 자리에 멈춰 설 수밖에 없었고 내부에 쌓여있는 '외침들이 마치 침묵의 회오리처럼 나를 감싸 안았다. 작가의 예술 행위에 결정적인 순간은 바로 그러한 경험에서 생성된다고 본다. 그것이 설명할 수 없는 에너지 그리고 그 에너지와 시간과 공간을 완전히 파괴하는 듯 초월하는 행위로서 예술가의 창작을 보다 잘 설명하는 것이 아닐까. -

최윤정

마찬가지로 내가 주목한 바는 행위자로서의 샤먼보다도 이를 문화원형적인 측면, 인 문학적인 요소와 연결지어 독해할 수 있지 않은가에 대한 부분이었다. 관련해서 동양의 문화

가 가지고 있는 샤먼 역사의 기원, 그것이 유불선 사상과도 연결되는 문맥이 있고, 그 역할이 유교의 성인, 노장사상에서의 신선과도 원형적 으로 문맥상 연결이 된다. 흔치 않으면서 아주 흥미로운 주제였다. 이것은 현대예술가에 대한 해석을 풍부하게 만들어 줄 수 있을 것 같다. -

김수자

이것은 우선적으로 예술적인 행위이자 동시대미술사 내지는 퍼포먼스의 문맥 안에서, 내가 어떤 관점을 우회적인 방식으로 선보일 수 있는가 전반을 고민하여 보여주는 것이기 때문에, 단순히 '샤먼' 즉 전적으로 접신이나 에너지 의 측면에서만 볼 수 없는 다양한 측면을 고려 할 필요가 있다. 구조적으로는 기독교적 측면, 불교, 도교적인 측면도 포괄한다고 본다. 그리고 다른 시각에서, 세계를 바라보는 4개의 관점. 제가 그 4방 혹은 8방을 향해서 바늘여인 퍼포먼스를 했다고 한다면 그 세계 전체를 아우르는 행위는 사방을 향한 '인류애'의 행위 그리고 그 인류애가 어디까지 위치지어져야 하는가를 일종의 시어로 표현한 수피즘도 있다. 즉 우리 문화의 어떤 한 현상으로 보기보다는 아주 복합적이고 다각적인 해석을 결합할 필요 가 있다. -

최윤정

보통은 분쟁적인 요소가 있는 지역이라면 혹자는 작가의 퍼포먼스를 일종의 저널리즘으로서 사태를 인식시키는 내용으로 읽을 수도 있을 것 같다. -

김수자

나는 사회 변혁을 위한 도구로서, 사태 자체를 직접적으로 선동하는 그러한 부분에 관심을 두지 않는다. 단지 그러한 문제점들을 늘 인지하고 있고, 바라보는 자로서 또한 바라볼 수 있게끔 매개하는 입장에 서있다. 이는 각각을 일대일 관계 안에서 해결해 보이려는 게 아니다. 관조하면서도 초월적인 입장을 견지하는 바다. 그 다음은 관객의 몫이다. 개개인의 경험과 감수성, 또 지적능력에 따라 각기 다른 체험을 하게 될 것이다. -

최윤정

노마디즘에 대해 말하고 싶다. 기존 인터뷰 내용들을 보니, 작가는 이에 대해 부정적인 입장은 아닌 것으로 보인다. 또한 일종의 현대인의 라이프 스타일로서 언급했던 바가 있다. 오히려 비평가들은 이동과 이주를 상징하는 보따리와 노마디즘을 자연스럽게 연결시키고 있는데, 이진경은 휘트니 비엔날레 시기, 테이블에 우리나라 전통 천을 씌웠던 작품을 보고 그것이 과연 노마디즘적이다라고 말한다. 이에 공감하는 바다. 오히려 이동이나 이주 및 정주를 상징하는 보따리보다는 자기 정체성, 습득하고 있는 고유한 문화 등이 이질적인 곳에 전통문양의 테이블보를 덮어씌움으로써 그 안에서 충돌하면서 새로운 가치가 생성된다고 보는 것이다. -

김수자

나 역시도 그러한 시각에 공감하는 부분이 있다. 또한 물론 거기에는 내 행위의 어떤 프로세스가 노마딕하다고 볼 수 있지 않을까. 그러한 의미에서 휘트니 뮤지엄에서 천을 펼쳐놓았건 베니스비엔날레에서 보따리 트럭을 가져다 놓았건 어쨌건 간에 그 또한 노마딕한 행위의 부분으로 드러날 수 있다. 어차피 현대인들 모두가 라이프스타일로서 노마딕한 삶을 살지 않을 수가 없는 시대이다. 그래서 현대의 노마디즘은 과거의 유유자적하고 자연친화적인 것이기보다는 실용적 의미에서 숨가쁜 도회적 사업(Urban global business)에 가깝다. 쉴새없이 세계적으로 소통하고 무소부재한(Omnipresent) 노마디즘이 횡행하고 있다고 해야 할까. 내 작업은 그야말로 자연과 관계를 맺으면서, 개인의 삶의 방식과 필요성들에 의해 어쩔 수 없이 펼치고 떠나가는, 노마디즘이라는 어휘조차도 필요하지 않은 그런 곳에 있다. 삶 속에서 저 개인의 고민과 문제점이 자연스럽게 펼쳐진 결과이다. 애초 노마디즘 자체 프레임 안에서 이루고자 했다든지 문화적인 문맥으로 의도한 바는 없었다. -

최윤정

이번 바늘여인(2005)에 대해서 실은 전작들, 광주학살의 희생자들을 기리는 작업(1995), 코소보 내전의 희생자들에게 헌정하는〈d'apertutto or Bottari Truck in Exile>(1999), 사우스캐롤라이나의 플랜테이션 농장에서 희생된 흑인들의 이름을 기록설치한 〈Planted Names>(2002)과 어떤 연계선상에 있다는 느낌을 받았다. 올리바 마리아 루비오의 평문에서도 와닿는 부분이었다. 담고자 하는 내용들 자체에 이미 태도적으로 엑티비스트 Activist로서 면모를 가지고 있지 않은가. -

김수자

혹자는 내 작업을 민중미술로 읽기도 하였다. 내 작업은 모더니즘과 민중적인 부분들을 함께 공유하고 있다고 생각한다. 그것은 미학적으로 추상과 구상 두 양식 과의 평행선에 있다고 보고, 나는 추상적(형식적) 영역과 구적 (현실적)영역을 함께 다루어 왔다. 어떤 집단적 운동(모더니즘 혹은 민중미술)이나 단체와 연계하지 않은 채, 철저하게 독립적으로 내 길을 택해왔다. 그리고 민중미술이라는 것이 우리나라의 경우 시대적 모순 정치적 현실을 기반으로 일어난 것이지만, 사실 나에게는 개인의 문제, 특히 제 개인의 존재론적인 열정이나 자기모순, 자기애가 그보다 우선이었다. 십여 년간 바느질sewing 작업을 행했던 그 모든 과정들을 열정을 보이고 자기에 대한 치유과정이었다고 한다면, 어느 순간 그 치유가 완료되었다 생각한 순간부터 나는 타인에 대한 치유에 많은 관심을 돌리게 되었다. 물론 바느질 작업을 하면서도 '나'라는 개인은 항상 뭐라 그럴까. 나의 보이지 않는 스토리나 아이덴티티를 드러내기 보다 타인의 몸을 빌려 즉 타인의 고통을 빌어서 나의 고통과 열정들을 담아왔기 때문에, 바느질이라는 물리적인 치유는 '바늘여인'이라는 행위하지 않으면서 치유하는 방식으로 변화되었다. 노마딕하다는 것 자체도 늘 자신의 자리를 버리는 자의 입장이 된다할까. 그래서 자신의 자리를 설정하고서 자기만의 성을 쌓는 게 아니고, 항상 자기 부정을 통해서 또 다른 세계로 자기를 열고 또다시 해체하고... 이러한 무수한 과정 들을 끊임없이 겪게 되는 행위들, 그러한 행위 가 또 다른 형태의 문답으로 자신에게 되돌아오기도 한다. -

최윤정

바느질 작업 이전 시기 예술가로서 자기로서 내적으로 가지고 있었던 상황들로부터 비롯된 문제의식에 대해 생각해본다. 그 과정이 지금 현재까지 이어져 '매개'와 더불어 본인과 세계, 인간과 인간, 자연의 요소적 관계에까지 소급해가는 것으로 보이는데, '관계'에 대해 보다 심도있는 의견을 듣고 싶다. -

김수자

사실 최초의 바느질 작업 자체가 하나의 관계에 대한 시각적인 표현이었다. 일종의 예술가의 진술로서 늘 처음부터 지금까지도 견지 되고있는 바다. 화가로서의 입장이 천이라는 따블로(Tableau)와 바늘이라는 상징적인 붓(brush), 도는 작가의 몸(body)을 통해 견지되어 왔던 바이고, 바느질은 따블로/평면에 대한 물음으로 점철되었고 그 평면은 타자(the other)이자 거울(Mirror)이었다. 그래서 바느질 행위는 자아와 타자의 구분을 넘나드는 행위이고, 이에 대해 의문을 갖고 답을 구하고자 하는 것이기 때문에, 어떤 의미에서는 형식상에서 회화에 대한 문제를 의인화시킨 것이라 보면 어떨까 한다. '평면'이 '인물'이 된 것이다. 내가 그동안 회화의 형식적인 탐구를 해온 것과 동시에 삶과 인간에 대한 탐구를 평면을 빌어 해 올 수 있었던 것도 알고 보면 조형적 양상과 삶의 양상이 둘이 아니기 때문이다.

3.

-

최윤정

장르의 폭이 넓다는 생각이 든다. 설치 작업에서부터 영상작업, 사운드 작업에 이르기까지, 모든 장르와 형식들에 대해 다양하게 접근하고 있는데, 혹여나 각각의 장르 선택에서 의도하는 바가 있는가. -

김수자

글쎄... 바느질sewing에서 오브제를 감싸는wrapping 작업으로 넘어가고 또 그것이 '보따리'로 감싸는 작업으로 넘어갔을 때, 그것은 사실 내가 어떤 논리나 미리 계획된 아이디어에 의해서 결정을 하는 것이기 보다는, 아주 즉각적인 반응에 더욱 근접한다. 거의 순간적인 예술충동이자 제 고유의 예술의지로 쌓여왔던 것이고, 그런데 또한 되돌아보면 그 안에 내적인 논리나 감수성 역시 있었던 바다. 그래서 감싸는wrapping 작업을 할 수 있었던 것은 최초로 의문을 갖곤 하였던 평면성과 바느질의 속성, 바느질 행위가 지니는 속성 안에 이미 그 감싸기wrapping의 속성이 있었기 때문에, 그것이 저절로 내 몸 속에서 풀어져 나온 것으로 생각한다. 평면적인 보따리 bottari로서 어느 순간 내 안으로부터 발견이 되었던 것이고, 그것이 자연스럽게 예술 충동에 의해서 연결이 되기도 하고, 뭐랄까 무엇으로부터인가 이끌린다는 느낌을 많이 받는다. 의도라기보다 이끌려 행할 수밖에 없는 그리고 그 행위가 결국은 다음 작업의 근거가 되어준다. 보따리 이후에는 새로운 공간의 체험을 통해서 그에 맞는 아이디어나 매체에 대한 실마리를 더욱 풀게 되었다. 이를테면 직조공장 위빙사운드를 생각해 냈던 것은 폴란드 우지(Lodz)에 비어있는 직조공간을 보면서 순간적으로 내 몸과 직조기계의 움직임을 병치하면서 들숨날숨과 직조의 유사성을, 또 음양의 요소나 삶과 죽음의 경계를 생각하게 되었고, 그래서 호흡(Breathing)사운드 퍼포먼스를 2004년도 우지비엔날레(Lodz Biennale)에서 선보이게 된 것이다. 나는 새로운 미디어에 대한 선택과 적용 의도에 있어서 무엇보다도 새로운 공간을 만나면서 혹은 새로운 문화, 문화적 원형, 자연적 구조 상에서 새로운 발상을 떠올린다. 그것은 미디어/장르를 발견하는 것보다 기존에 갖고 있던 나의 질문과 고민들을 더 심화되는 바와 마찬가지로 동일한 선상에서 미디어가 발견된다는 표현이 더 적합 할 것 같다. 그래서 내가 선택하는 미디어는 작업개념의 심화에 따라 시작된 것이지, 미디어/장르 자체에 대한 것은 아니다. 비디오 작업 역시도 카메라렌즈가 세상과 사람을 잇는 선상에서 개념적으로 의미를 부여할 수 있기에 시작된 바다. -

최윤정

주로 해외를 중심으로 많은 활동을 선보이고 있다. 내년 전시 일정 및 지금 현재 진행 하고 있는 혹은 의미있게 바라볼 만한 프로젝트를 소개해달라. -

김수자

내년에도 유럽과 아시아 미국에서의 몇몇 개인전과 단체전이 기획되어 있다. 로잔의 IOC올림픽 미술관과 아리조나와 멕시코 국경에 설치할 미국정부에서 커미션한 비디오 설치 작업들로 쉴 새 없이 일해야 할 것 같다. 그 외에 현재 진행하고 있는 프로젝트는 바늘여인의 대척점에 있는데, 바늘여인이 바늘의 궤적을 찾는 작업이라면, '실의 여정(Thread Routes)이라는 실의 궤적을 추적하는 작업이다. 'Thread roots'로 생각해도 좋을 것 같다. Roots(근원)로부터 Routes(길)에 도달하는 삶의 여정이라고 할까. -

대구미술관 프로젝트룸(B1F), 2011년 12월 5일 월요일

참여: 김수자 작가/ 진행 : 최윤정 큐레이터

─ Interview on December 5, 2011. from Exhibition Catalogue 'Kimsooja' published by Daegu Art Museum, Korea. 2012, pp.404-411.

The Heaven and the Earth, 1984, Used clothing fragments, acrylics, Chinese ink on canvas cloth, 190 x 200 cm

The Heaven and the Earth, 1984, Used clothing fragments, acrylics, Chinese ink on canvas cloth, 190 x 200 cm

Kimsooja: Contemplation on top of the Horizontal and Vertical System

Suh Young-Hee (Art Critic and Professor at Hong Ik University, Seoul)

2012

Time and space of the horizontal and the vertical

-

When the vertical and the horizontal meet, they form a cross. As they come together as a cross, harmony comes forth in a relation of interdependence. Even when seeing the horizontal line and the vertical line separately, we easily conjure up their intersection. From the early ages of primitive culture or ancient culture, the repetition or rearrangements of the horizontal and vertical lines were used as signs for arithmetic, or further as symbolic signs for communication and letters. The cross being formed as a result of the perpendicular intersection was considered a sign of perfection, more so than the square composed of two sets of equally measured horizontal lines and vertical lines, particularly because of the conception that its centripetal force was greater. The ┼ even when turned over to an ╳ was regarded as a sign of perfection that displayed harmony and completion. This is why the ancient Latins devised to write ╳ after the number nine, and the ancient Chinese also used ┼ as their sign for ten. The human body as a measure of the world is also in the form of a cross. The human limbs and organs are structured centripetally: the body with arms spread and legs together form ┼, and the copy of the human body drawn by Vitruvius in AD 1st century and later again by Leonardo da Vinci forms an ╳ with all the limbs spread apart. Furthermore, the cross symbolically signified the connection between the heavens - the world of the gods - and earth. Considered as a connection between the transcendental world and the secular world, the intersection of the horizontal line and the vertical line is also called the 'world's axis.' Let us look at the cross in Christianity and the swastika(卍) in Buddhism. The former signifies the tribulations on earth and glory in heaven and the latter refers to the cosmic symbol of the connection of heaven and earth; both imply psychological healing as well as religious salvation. Thus in Western culture, the cathedral - the dwelling place of God - had as its basis the floor plan of a cross as well as the cruciform vault, and the mandala in Hinduism and Buddhism had as its basic structure the cross intersection of the horizontal and the vertical, symbolizing the order of the cosmos that pointed towards the heavens and the earth. The cross structure, divided into four areas of the upper-lower hemispheres and the left-right hemispheres, also symbolized the different aspects of a human being: the cognitive and sensory, the intuitive and affective. One can find both in the Confucianist Book of Changes and in Buddhism that the four directions in the horizontal-vertical intersection symbolize the cosmic order formed by water, earth, fire and wind. As is well known, the Korean vowels also make use of the horizontal and vertical lines: ㅡ as earth, ㅣas the sky, and the middle dot as the human.

-

The horizontal-vertical form frequently appears in art as well. From the primitive arts to contemporary, from decorative art to fine art, the horizontal-vertical lines generally appears as signs that signify the universe and man. When looking at ancient art and primitive artifacts, one frequently finds horizontal-vertical intersections, cross structures, and grids on murals, ceramics, textile and basket weaving, etc. As explicated in art psychology, this phenomenon may be derived from the human effort to control and impute order upon a world, or nature, that is otherwise too vast and unpredictable. Wilhelm Worringer, too, explains the horizontal-vertical structure in his 'Abstraction and Empathy' as an order standing in contrast to the disorder of nature. Commentaries on abstract art generally mention Cezanne's attitude that reorganized nature into a sturdy order of geometry as well as the geometric abstraction of Kandinsky and Mondrian's horizontal-vertical system and Klee's hieroglyph-like symbol paintings as a way to elucidate that the context of the horizontal-vertical system is the expression of the abstract painters' worldview. This form of argument, taking the form of structuralist epistemology, argues that the horizontal-vertical structure perceived as a symbol of man and the universe has been generally inherited in artists from the primitive ages to contemporary times (i.e., ranging from the grid work in minimalist paintings to cross-like shaped-canvas). The cross as an intersection of the horizontal and vertical lines is an extremely condensed sign, implying with the lines' directions all five senses of humans, inner psychology and even spiritual content, thus rendering inevitable to admit that the artist's faculty for abstraction operates in tandem. The anthropologist Levi-Strauss, having been much interested in art, explains in his "Elementary Structures of Kinship" that the basic structure of dichotomy that formed an internal relation of interdependence is effectively at work in various cultures and arts, an argument aided by the Saussurean intersection of the diachronic and synchronic (horizontal and vertical, respectively) axes.

-

Kimsooja, the subject of this article, is surely a painter, though she does not paint on the canvas. Instead, she is an artist who takes as her premise the horizontal-vertical structure as a general order for the world and mankind, further expressing this premise by coupling it with metaphysical thought. In this respect, the works of Kim is an interesting metaphor on the world, her series a continuous metonymy on the horizontal-vertical structure. The meditation on the basic structure of the horizontal and the vertical is consistently in effect as the logic and archetype of her production, manifested from the fabric-weaving series, "Sewing," through "Deductive Objet" all the way to the "Needle Woman" series and "Earth, Water, Fire, Air" series. In this respect, it is important to remember that the artist herself has repeatedly mentioned in interviews – and especially in her master's thesis, "A Study on the Universality and Hereditariness of the Plastic Sign: A Focus on the Cruciform Sign (1984)" –that, like the Eastern yin and yang, the binary structure of the horizontal and vertical is the fundamental system which encompasses and composes the world. This article intends to examine, albeit briefly, the transition of Kim's thought from canvas to fabric as well as how the horizontal and vertical lines and their cruciform intersection are actualized in her work.

The Transition of Thought I: From Canvas to Fabric

-

For Kim, the tools for expression are no longer limited to the canvas, paint and brush. The flat surface and rectangular stretcher of the canvas is but a tool for representation, whether concrete or abstract, a rigid device that in inapt to take the place of the free flow of thought. Thus the artist selects from fabric, a flexible material among the components of the canvas. The "Sewing" series (1983-1988), the first work with fabric, brought forth works of indeterminate forms, sewing together various scraps of fabric. If one would insist on calling these pictorial art, would it be considered a kind of Color Field abstractionism? But in contrast to the hard-edge or Color Field paintings of 70s America, one does not find the homogeneity of the color surface or a precisely cut contour. Rather, the different scraps of fabric, varying in size and stained with traces of drawing, are connected without being tidied up – their surfaces rugged, edges irregular and seams tattered. In place of an artist's will for perfection, the materiality proper to fabric is wholly accentuated. Even still, this should not be categorized under a kind of Dadaist act of choosing anti-aesthetic objets or a tendency for conceptual art. Fabric and sewing is Kim's subject matter by which she expresses the world of humans like herself–entangled, knotted, and contemplating the fundamental structures of the world. Pieces of fabric are linked both horizontally and vertically, sewn in a manner that is interdependent and mutually supportive. As a result, the fact that the 'woven' scraps sustain a horizontal-vertical structure without sagging down despite the disappearance of the stretcher is called to our attention. Replacing the wooden stretcher, the source of the tautness that pulls the fabric is the relational device, that is, the 'countless stitches of sewing.' Thus is the support that holds the balance between gravity and the pieces of fabric.

-

Here, I would like to mention the source by which the work's order is formed: the binary structure between the tension of the needlework and the flexibility of the fabric. It is often regarded as merely coincidental this appearance of the working with sewn fabric pieces. As the artist repeatedly mentioned, this method suddenly crossed her mind in 1983 as she was tacking up the duvet cover with her mother. This anecdote is well known through various writings, but I reference it once more, for it offers a clue to the embarking of the artist's distinct art world: "In the quotidian act of tacking up bed sheets with my mother, I experienced an intimate yet wonderful sense of unity of my thoughts, sensibilities and actions. I found the possibility to contain such abundance of memory and pain, even the affection for life in that unity. The weaving of the weft and warp as a basic structure of the fabric, our primordial sense of color in our fabrics, the self-identification with fabric in the act of weaving through flat surface, and the strange nostalgia evoked in it… all of this was entirely mesmerizing." (The Artist's Notes, 1988 Gallery Hyundai) Later the artist reminisces this experience, remarking that the moment she tacks the pointy needle into the fabric, she feels the energy of the universe penetrating her entire body. This astounding anecdote on a rather serendipitous experience would be repeated in every of her interviews, becoming a clue that renews our awareness to what the archetype of her work is.

-

I would like to interpret the 'moment she tacks the point needle' into the duvet cover spread across the floor as a ground breaking moment of penetrating the surface screen of pictorial art that persisted for several hundred years. Like the Spatialist painter Lucio Fontana who pierced the uni-colored canvas with a sharped-edged dagger, Kim also realized pictorial art that was no longer a screen of illusion but a three-dimensional structure as she weaved through the surface of the duvet cover, piercing holes into it. What is of particular importance here is the perpendicular penetration of the needle into the sheets horizontally spread on the floor. This three-dimensional relation between horizontality and verticality is thought to be a decisive opportunity for Kim - only familiar with the illusion of the surface - to identify the reality of painting, or the hidden structure of the canvas. For some time, pictorial art has been identified as a conceptual representation of the illusion created by the screen of paint covering the canvas surface. But once the shift in thought takes place where the signifiers, or the structural elements – the materiality of color, the fabric of the canvas, the wooden stretcher that supports the screen – is thought to define the meaning of painting, the modernist equation of 'painting = flat, rectangular screen' is also rendered null. Further more, when one stretches the canvas or the bed sheets, it sees that they are also products of the horizontal-vertical system where threads are intersecting. When Kim decided to suspend the bed sheets in the exhibition center for the audience to be able to see both sides of the fabric, this method of installation was of particular importance in terms of confirming the three-dimensionality and spatial topology of fabric.

Transition of Thought II: From Sewing to Deductive Objet to Bottari

-